Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army

This escalation in Japanese imperial expansion occurred alongside the Great Depression, during which thousands of Malayan workers were left unemployed.

The country's large workforce of Chinese and Indian immigrants that had previously fueled the rubber industry's regional boom suddenly found themselves out of work[citation needed].

Driven by political, racial, and class solidarity, young Chinese immigrants joined the growing Malayan Communist Party (M.C.P.)

Anti-Japanese sentiments among the Malayan populace reached new heights when Japan declared war on China in 1937[citation needed], which increased the membership and political influence of the M.C.P.

Additionally, the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had formed a united front against the Japanese invasion in mainland China.

Most of the Chinese guerillas were ill-prepared, both mentally and physically, to live in the jungle, and the toll from disease, desertions, enemy attacks and insanity increased by the day".

The desire for revenge against the Japanese inspired many young Chinese to enlist with the MPAJA guerrillas, thus ensuring a steady supply of recruits to maintain the resistance effort despite suffering from heavy losses.

In his book Red Star Over Malaya, Cheah Boon Keng describes Lai Teck's arrest as such: In August 1942 Lai Teck arranged for a full meeting which included the MCP's Central Executive Committee, state party officials, and a group leaders of the MPAJA at the Batu Caves, about ten miles from Kuala Lumpur.

Another individual would be Liao Wei-chung, also known as Colonel Itu, who commanded the MPAJA 5th Independent Regiment from 1943 till the end of the war.

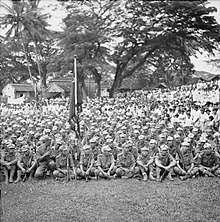

The MPAJU pursued an open policy of recruiting people regardless of race, class, and political belief as long as they were against the Japanese regime.

The MPAJA recruited manpower by organising volunteer units called the Ho Pi Tui (Reserves) in villages, towns and districts.

The first party, consisting of Colonel John Davis and five Chinese agents from the Special Operations Executive organisation called Force 136, landed on the Perak coast on 24 May 1943 from a Dutch submarine.

[7] Other groups followed, including Lim Bo Seng, a prominent Straits-born Chinese businessman and KMT supporter who volunteered to join the Force 136 Malayan Unit.

[11] The MPAJA agreed to accept the British Army's orders while the war with Japan lasted in return for arms, money, training, and supplies.

[6] It was also agreed that at the end of the war, all weapons supplied by Force 136 would be handed back to British authorities, and all MPAJA fighters would disarm and return to civilian life.

[7] However, Force 136 was unable to keep several pre-planned rendezvous with its submarines, and had lost its wireless sets; the result was that Allied command did not hear of the agreement until 1 February 1945, and it was only during the last months of the war that the British were able to supply the MPAJA by air.

[6] Between December 1944 and August 1945, the number of air drops totalled more than 1000, with 510 men and £1.5 million worth of equipment and supplies parachuted into Malaya.

Although the MCP and MPAJA consistently espoused non-racial policies, the fact that their members came predominantly from the Chinese community caused their reprisals against Malays who had collaborated to be a source of racial tension.

A gratuity sum of $350 was paid to each disbanded member of the MPAJA, with the option for him to enter civilian employment or to join the police, volunteer forces or the Malay Regiment.

One particular incident reinforced this suspicion when the British army stumbled upon an armed Chinese settlement that had its own governing body, military drilling facilities and flag while conducting a raid on one of the old MPAJA encampments.

Although there was no direct evidence that all leaders of these associations were communists, representatives of these veteran clubs participated in meetings with communist-sponsored groups that passed political resolutions.

[6] Cheah Boon Keng argues that these ex-guerrilla associations would later become well-organised military arms for the MCP during its open conflict with the BMA in 1948.

[6] The 5th Regiment was considered the strongest under the leadership of Chin Peng, then-Perak State Secretary of the MCP, and Colonel Itu (aka Liao Wei Chung).

When not engaged in guerrilla activities, a typical life in an MPAJA camp consisted of military drilling, political education, cooking, collection of food supplies, and cultural affairs.

[8] The Central Military Commission, which was "reorganized to take full control of the MPAJA", was headed by MCP leaders "Lai Teck, Liu Yao and Chin Peng".

[6] On the other hand, historian Lee Ting Hui argues against the popular notion that the MCP had planned to use the MPAJA to invoke an armed struggle against the British.

[5] The MCP had adopted Mao Tze Dong's strategy of a "peaceful struggle", which was to take over the countryside and get "workers, peasants and others" to conduct "strikes, acts of sabotage, demonstrations, etc.

[6] Ban and Yap agree with Cheah in his figures, mentioning that the MPAJA "claimed it had eliminated 5,500 Japanese soldiers and about 2,500 'traitors' while admitting that they had lost some 1,000 men".

[8] However, Ban and Yap feel that the Japanese might have "under-reported their casualties as the MPAJA had always been depicted as a band of ragged bandits who could pose no threat to the Imperial Army".

[7] On the other hand, Tie and Zhong felt that "if the atomic bomb had not put an abrupt end to the 'war and peace' problems, the anti-Japanese force could have achieved even more".