Manchester Baby

It was built at the University of Manchester by Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn, and Geoff Tootill, and ran its first program on 21 June 1948.

Described as "small and primitive" 50 years after its creation, it was the first working machine to contain all the elements essential to a modern electronic digital computer.

[3] As soon as the Baby had demonstrated the feasibility of its design, a project was initiated at the university to develop it into a full-scale operational machine, the Manchester Mark 1.

[2] The first design for a program-controlled computer was Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine in the 1830s, with Ada Lovelace conceiving the idea of the first theoretical program to calculate Bernoulli numbers.

[6] Konrad Zuse's Z3 was the world's first working programmable, fully automatic computer, with binary digital arithmetic logic, but it lacked the conditional branching of a Turing machine.

It was Turing complete, with conditional branching, and programmable to solve a wide range of problems, but its program was held in the state of switches in patch cords, rather than machine-changeable memory, and it could take several days to reprogram.

[16] The NPL did not have the expertise to build a machine like ACE, so they contacted Tommy Flowers at the General Post Office's (GPO) Dollis Hill Research Laboratory.

Flowers, the designer of Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, was committed elsewhere and was unable to take part in the project, although his team did build some mercury delay lines for ACE.

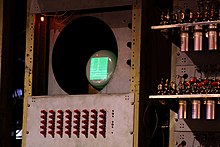

[15] Williams led a TRE development group working on CRT stores for radar applications, as an alternative to delay lines.

[17] Williams was not available to work on the ACE because he had already accepted a professorship at the University of Manchester, and most of his circuit technicians were in the process of being transferred to the Department of Atomic Energy.

[15] Although some early computers such as EDSAC, inspired by the design of EDVAC, later made successful use of mercury delay-line memory,[18] the technology had several drawbacks: it was heavy, it was expensive, and it did not allow data to be accessed randomly.

Williams had seen an experiment at Bell Labs demonstrating the effectiveness of cathode-ray tubes (CRT) as an alternative to the delay line for removing ground echoes from radar signals.

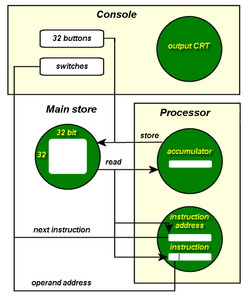

[19] The Baby was designed to show that it was a practical storage device by demonstrating that data held within it could be read and written reliably at a speed suitable for use in a computer.

[23] Having secured the support of the university, obtained funding from the Royal Society, and assembled a first-rate team of mathematicians and engineers, Newman now had all elements of his computer-building plan in place.

Adopting the approach he had used so effectively at Bletchley Park, Newman set his people loose on the detailed work while he concentrated on orchestrating the endeavor.Following his appointment to the Chair of Electrical Engineering at Manchester University, Williams recruited his TRE colleague Tom Kilburn on secondment.

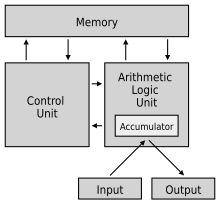

"Kilburn had a hard time recalling the influences on his machine design: [I]n that period, somehow or other I knew what a digital computer was ... Where I got this knowledge from I've no idea.Jack Copeland explains that Kilburn's first (pre-Baby) accumulator-free (decentralized, in Jack Good's nomenclature) design was based on inputs from Turing, but that he later switched to an accumulator-based (centralized) machine of the sort advocated by von Neumann, as written up and taught to him by Jack Good and Max Newman.

[27] Although Newman played no engineering role in the development of the Baby, or any of the subsequent Manchester computers, he was generally supportive and enthusiastic about the project, and arranged for the acquisition of war-surplus supplies for its construction, including GPO metal racks[29] and "…the material of two complete Colossi"[30] from Bletchley.

[42] The machine's successful demonstration quickly led to the construction of a more practical computer, the Manchester Mark 1, work on which began in August 1948.

The first version was operational by April 1949,[41] and it in turn led directly to the development of the Ferranti Mark 1, the world's first commercially available general-purpose computer.

[4] In 1998, a working replica of the Baby, now on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, was built to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the running of its first program.