Mannerism in Brazil

Over the years the current was added of new elements, coming from a context deeply disturbed by the Reformation, against which the Catholic Church organized, in the second half of the sixteenth century, an aggressive disciplinary and proselytizing program, the so-called Counter-Reformation, revolutionizing the arts and culture of the time.

However, the imitation of nature was loaded with formalism and idealism, it proposed the presentation of a utopian world, where Good reigns on Earth under the benevolent power of Heaven, and differences are annulled under a great homogenization of culture and way of life, where people follow a pure and altruistic ethic.

[2][3][4][5] Then, Mannerism is, first of all, the fruit of these profound changes in Italian society, and if before the classical values of the High Renaissance could still preserve a façade of cultural unity and of an optimistic and peaceful world, in a short time even art was no longer able to sustain it, appearing works that were ambiguous, agitated, questioning, not infrequently cynical, hedonistic, irrational, hermetic, precious and frivolous, and even bizarre, obscure, fantastic and grotesque.

Therefore, Mannerism confronted Classicism advocated and that had proven to be an ideal too high to be materialized, presenting the world as a place of conflicts, contradictions, uncertainties, insufficiencies, and dramas, where violence, falsehood, and cruelty were habitual political methods, religious dogmatism subjugated consciences and wills, hunger, wars, and epidemics were constant threats, and simple survival was for the vast majority of people a poignant and pressing challenge.

[12] Throughout the evolution of Mannerism, the classical reference, in fact, was not eliminated from art, but rather it was tested, discussed, relativized, disarticulated, transformed, and even combated, but it remained the basis on which later advances emerged, adapting it to a new social, political, and cultural universe.

Renowned Italian engineers and architects settled in our country, such as Benedict of Ravenna and Filippo Terzi, Giovanni Battista Antonelli and Giovanni Vincenzo Casale (and, later, Leonardo Turrano), contributed decisively to the full acceptance, in the Portuguese Empire, of a Mannerist architecture with a sui generis feature, curiously with a much more extensive chronological development than the other artistic branches, which already in the first third of the 17th century received the naturalistic influxes of the Baroque.Portuguese painting was particularly sensitive to influences from Italy, which our more erudite workshops picked up (directly and almost immediately) - a statement that is based on an analysis of the pictorial legacy of the same period.

Adriano de Gusmão, who talks about the importance of a Flemish diffusion route when he considers that it was still through Antwerp - as it had been before - that our painting was converted to the Mannerist models, does not exclude "the simultaneous and probable direct contact of some of our artists with Italian means", suggested by the clear influence of Vasari that can be seen in some Portuguese altarpieces of the time, not only in the composition but also in the color.

At the same time, as the spiritual needs of the new settlers had to be met, the Catholic Church participated in the settlement process by sending many missionaries, among them Jesuits, Dominicans, Carmelites, Benedictines and Franciscans, who in general had a solid cultural background, many of them also being talented artists, the founders of Brazilian art with European descent.

The heterogeneity of the influences received, along with the difficulties of communication with the mainland, created a gap in relation to the aesthetic chronology of Europe, and caused the evolution of Brazilian art to be marked by large doses of eclecticism and that archaisms persisted for a long time.

[9][27] Due to the sacred character of the vast majority of the most important buildings erected in the colony, the influence of the aesthetics cultivated by the different religious orders was decisive in shaping Brazilian architectural Mannerism, with the Jesuits and, to a lesser degree, the Franciscans as its most active representatives.

The great versatility and practical viability of the Plain Style served the interests of both the Church and the Portuguese State, at a time when both were closely united through the patronage system, with the religious being important agents in the organization and education of society and also in the process of building the overseas empire.

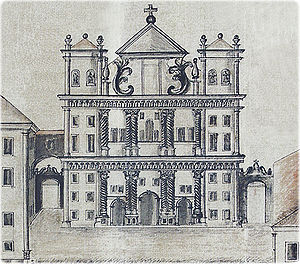

[28] The facades were as a rule extremely simple, derived from the classical temple model, with a square or rectangle as the main body, pierced by a row of straight lintel windows on the upper level, and crowned by a triangular pediment.

[37][40][41] Despite the prioritization of functionality in fortifications, military engineers were well prepared and often well informed about the art and erudite architecture of their time, as evidenced by their knowledge of the treatises of Vitruvius, Vignola and Spannocchi, among others, their frequent collaboration in religious constructions and the many projects they left for churches and chapels.

[42] In São Paulo, the military engineer João da Costa Ferreira was praised by Governor-General Bernardo José de Lorena, who mentioned that he was loved by the people due to his performance teaching everyone how to build well with local resources.

Brigadier José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim is considered the diffuser of arched lintels on windows and doors in the mid-18th century with his project for the Palace of the Governors in Ouro Preto, which became an almost ubiquitous pattern in civil construction, strongly associated with the Baroque style.

[...] The military engineers, in the isolation of the colony, were naturally impelled to assist the population by helping to construct the definitive buildings to replace the primitive syncretic examples erected with materials and techniques borrowed from the local inhabitants, especially convents and churches.

[...] Finally, those technicians have the merit of spreading throughout Brazil a single architecture, from Porto Alegre to Belém, giving the reason to the French engineer Louis-Léger Vauthier, in Recife, in the middle of the XIX century, when he pronounced a truthful shot: 'Who has seen one Brazilian house, has seen them all'.

[27]Manor houses, colleges, and monasteries are other noteworthy typologies that were built with simple, regular lines and decorative austerity in the facades, with straight lintel windows and occasionally a discreetly ornamented portal, seeking functionality rather than luxury.

In sculpture, traces of a classicism almost only appear in the early production of sacred statuary, characterized by its solemnity and staticity, by faces with impassive expression, and by vestments that fall flat to the ground, which contrast with the bustling and dramatic patterns of the Baroque from the 17th century on.

[1]However, unlike the Franciscans, who early on adopted the luxurious Baroque patterns, the Jesuits preserved in the gilded carving of the altars classicist archaisms and a sense of greater sobriety, with a low volumetric treatment, little dynamism in the forms, the use of isolated columns with straight shafts, abundance of geometric motifs, a high quality craftsmanship and a division of the areas based on rectangular planes.

[59][60][61] In a separate setting, a remarkable artistic flourishing occurred around the court of the Dutch invader Maurice of Nassau, established in Pernambuco between 1630 and 1654, gathering illustrators, painters, philosophers, geographers, humanists and other specialized intellectuals and technicians.

In painting, the figures of Frans Post and Albert Eckhout stand out, leaving works of high quality and within a calm and organized classicist spirit that has little affinity with the more typical nervous and irregular pictorial Mannerism, and that until today are one of the most important primary sources for the study of landscape, nature and the life of indigenous peoples and slaves of that region.

On the other hand, the allegorical and decorativist character of Eckhout's compositions and his tendency towards the artificial "whitening" of the blacks and the indigenous peoples, and the doses of fantasy and incongruities in the montage of scenes that could not have existed in reality in Post, both created images that had a cultural and political programmatic content recognized and made explicit at that very time, and were more the materialization of the desires and idealizations of the nobility and the illustrated bourgeoisie in Netherlands - who bought his works and mythified the tropical world - than scientific descriptions of the land, are elements that in some ways bring them closer to the mannerists.

Another great example, of a very pure Mannerism, is the sacristy ceiling of the Cathedral-Basilica of Salvador, derived from the Roman-inspired Grottesque style, with a series of medallions inserted in the wood carving, with floral frames and portraits of Jesuit saints and martyrs in the center.

There were no schools except for those run by priests and study was practically limited to basic literacy and religious catechesis, illiteracy was widespread, the press was forbidden for a long time, the circulation of books was very small and invariably passed through the sieve of government censorship, generally being chivalric romances, catechisms, almanacs and some dictionaries and treatises about law, legislation and Latin.

However, Mannerist traces are clearly perceptible in many moments, in particular due to the overwhelming influence of Camões in the metropolitan literary production, who shows his Mannerism through the intense atmosphere of political and spiritual crisis in his writings, in the absence of any certainty, in his famous feeling of disenchantment and melancholy towards the lost "classical paradise", in the opposition between the high ethics of Renaissance humanism and the perception of real man's inadequacies and wickedness, in the strangeness and desire to escape from the world, in the religious propaganda, in the use of complex figures of speech and artful gimmicks, and in the taste for contrast, emotional excitement, conflict, paradox, dreamlike and fantastic atmospheres, and even the grotesque and the monstrous.

[87] Around the same time Eugenio Battisti and Hiram Haydn wrote influential and thoughtful works dealing with varied aspects and demanding a revision in historical categories,[53] Wolfgang Lotz studied its architecture and better defined its chronology,[86] and Walter Friedländer refined his periodization and refuted the idea that the movement was a decadence of the Renaissance.

[88][53] More recently Georg Weise analyzed the influence of the Gothic and made one of the best distinctions between Mannerism and the Baroque,[89][53] Ernst Robert Curtius left perhaps the best study on the literature,[90] and Gustav René Hocke devoted himself to the philological aspects in an anti-historicist approach.

Roberth Chester Smith and John Bury, in several essays published between the 1940s and 1960s, on the other hand, already embraced it in its full legitimacy, applying it to describe with consistency and depth broad sectors of national art, focusing however on the study of architecture.

Rafael Schunk gave great attention to Brazilian Mannerism in its various artistic expressions in his master's dissertation Frei Agostinho de Jesus e as tradições da imaginária colonial brasileira - séculos XVI-XVII (2012).