Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanists sought to create a citizenry able to speak and write with eloquence and clarity, and thus capable of engaging in the civic life of their communities and persuading others to virtuous and prudent actions.

During the period, the term humanist (Italian: umanista) referred to teachers and students of the humanities, known as the studia humanitatis, which included the study of Latin and Ancient Greek literatures, grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy.

[3] Very broadly, the project of the Italian Renaissance humanists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the studia humanitatis: the study of the humanities, "a curriculum focusing on language skills.

According to one scholar of the movement, Early Italian humanism, which in many respects continued the grammatical and rhetorical traditions of the Middle Ages, not merely provided the old Trivium with a new and more ambitious name (Studia humanitatis), but also increased its actual scope, content and significance in the curriculum of the schools and universities and in its own extensive literary production.

[6]However, in investigating this definition in his article "The changing concept of the studia humanitatis in the early Renaissance," Benjamin G. Kohl provides an account of the various meanings the term took on over the course of the period.

The rediscovery, study, and renewed interest in authors who had been forgotten, and in the classical world that they represented, inspired a flourishing return to linguistic, stylistic and literary models of antiquity.

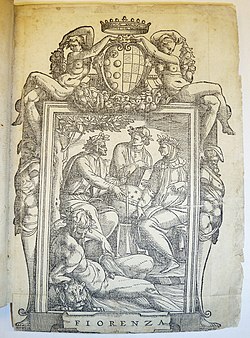

There were important centres of Renaissance humanism in Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Genoa, Livorno, Mantua, Padua, Pisa, Naples, Rome, Siena, Venice, Vicenza, and Urbino.

Italian humanism spread northward to France, Germany, the Low Countries, Poland-Lithuania, Hungary and England with the adoption of large-scale printing after 1500, and it became associated with the Reformation.

In France, pre-eminent humanist Guillaume Budé (1467–1540) applied the philological methods of Italian humanism to the study of antique coinage and to legal history, composing a detailed commentary on Justinian's Code.

[20] Much humanist effort went into improving the understanding and translations of Biblical and early Christian texts, both before and after the Reformation, which was greatly influenced by the work of non-Italian, Northern European figures such as Erasmus, Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, William Grocyn, and Swedish Catholic Archbishop in exile Olaus Magnus.

The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy describes the rationalism of ancient writings as having tremendous impact on Renaissance scholars: Here, one felt no weight of the supernatural pressing on the human mind, demanding homage and allegiance.

Renaissance Neo-Platonists such as Marsilio Ficino (whose translations of Plato's works into Latin were still used into the 19th century) attempted to reconcile Platonism with Christianity, according to the suggestions of early Church Fathers Lactantius and Saint Augustine.

In this spirit, Pico della Mirandola attempted to construct a syncretism of religions and philosophies with Christianity, but his work did not win favor with the church authorities, who rejected it because of his views on magic.

Dutch Renaissance and Golden Age Though humanists continued to use their scholarship in the service of the church into the middle of the sixteenth century and beyond, the sharply confrontational religious atmosphere following the Reformation resulted in the Counter-Reformation that sought to silence challenges to Catholic theology,[30] with similar efforts among the Protestant denominations.

[31] A number of humanists joined the Reformation movement and took over leadership functions, for example, Philipp Melanchthon, Ulrich Zwingli, Martin Luther, Henry VIII, John Calvin, and William Tyndale.

First coined in the 1920s and based largely on his studies of Leonardo Bruni, Baron's "thesis" proposed the existence of a central strain of humanism, particularly in Florence and Venice, dedicated to republicanism.

During the period in which they argued over these differing views, there was a broader cultural conversation happening regarding Humanism: one revolving around Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger.

[35] Hankins summarizes the Kristeller v. Garin debate as: According to Russian historian and Stalinist assassin Iosif Grigulevich two characteristic traits of late Renaissance humanism were "its revolt against abstract, Aristotelian modes of thought and its concern with the problems of war, poverty, and social injustice.