Manuel Torres (diplomat)

During the Spanish American wars of independence he was a central figure in directing the work of revolutionary agents in North America, who frequently visited his home.

[1] In the spring of 1776 the young Torres sailed to Cuba with his maternal uncle Antonio Caballero y Góngora, who was consecrated there as bishop of Mérida in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (modern Mexico).

[3] Torres went to France in early 1785 to study at the École Royale Militaire at Sorèze [fr], where he spent about a year and half learning military science and mathematics.

As lieutenant of engineers (Spanish: teniente de ingenerios) he probably aided Colonel Domingo Esquiaqui's survey and helped reorganize the colonial garrisons.

[4] On presentation by the archbishop-viceroy, Torres was gifted land near Santa Marta by Charles IV and established a successful plantation, which he named San Carlos.

[5][6] He became involved with political liberals of Bogotá's criollo class (i.e., native New Granadians of European descent), joining a secret club led by Antonio Nariño where radical ideas were discussed freely.

[17] Although President James Madison's administration officially recognized no governments on either side, Patriot agents were permitted to seek weapons in the U.S., and American ports became bases for privateering.

Torres acted as an intermediary between the newly arrived agents and influential Americans, such as introducing Juan Vicente Bolívar [es] (Simón's brother) to wealthy banker Stephen Girard.

Girard agreed to finance the plan on the joint credit of Buenos Aires and Venezuela, but Secretary of State James Monroe blocked it by refusing to reply.

The lengthy book's title page styles Torres and Hargous as "professors of general grammar"; in the introduction they argue the importance to Americans of studying Spanish literature.

Structured as a dialog, the anonymous pamphlet offers a defense of the U.S. system of government based on the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and argues it should be a model for Spanish America.

[25] Torres' lobbying included domestic affairs; in February 1815, near the end of War of 1812 that had preoccupied the American public, he wrote two letters to President Madison describing a proposal for fiscal and financial reform.

[27] This included an equal and direct tax on all property, which Torres considered more just; ultimately he calculated a $1 million budget surplus under his scheme and suggested gradual elimination of the national debt.

In his December 5 message to Congress, Madison did propose two ideas that Torres had favored: the establishment of a second Bank of the United States and utilizing it to create a uniform national currency.

Torres plays on Anglo-American rivalry by arguing for the importance of establishing American over British commercial interests in this critical region, just as revolutionary agents in Britain suggested the opposite.

Through Clay, Torres suggested to Congress that he had discovered a new way to make revenue collection and spending more efficient, which he would reveal in detail if he was promised a share of the government's savings.

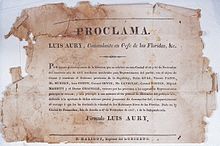

They were joined by a number of other agents to form a "junta" of their own, which included Orea, Mariano Montilla, José Rafael Revenga, Juan Germán Roscio from Venezuela, Miguel Santamaría from Mexico, as well as Vicente Pazos [es] from Buenos Aires.

But the plotters were able to organize a force under the recently arrived General Francisco Xavier Mina (despite the obstructions of José Alvarez de Toledo, an acquaintance of Torres who was actually spying for Onís).

When Torres received his diplomatic credentials he was authorized "to do in the United States everything possible to put an immediate end to the conflict in which the patriots of Venezuela are now engaged for their independence and liberty."

[39] With the help of Samuel Douglas Forsyth, an American citizen sent from Venezuela by Bolívar, Torres was instructed to procure thirty thousand muskets on credit.

[42] Although Torres repeatedly wrote to his superiors about the great importance of maintaining Colombia's credit among American merchants, the government failed to make payment as agreed.

However, Secretary of State Adams emphatically spoke against what he considered a violation of American neutrality, causing the cabinet to unanimously decline the request in a meeting on March 29.

Despite continued negotiation this loan was never finalized—let alone Bolívar's bolder proposal for the Bank to take on the entirety of Venezuela's national debt in exchange for the Santa Ana de Mariquita silver mine in New Granada.

Historian José de Onís mentions that "some Spanish American critics assert that Torres' works are generally regarded as having been written by Mier and Vicente Rocafuerte.

"[56] In particular, Bowman believes a pamphlet bearing Mier's name, La América Española dividida en dos grande departamentos, Norte y Sur o sea Septentrional y Meridional, was actually Torres' work.

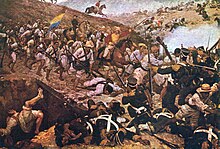

He glorified its achievement of near-total military victory, the extent of its population and territory, and its potential for commerce:[62] She also unites by prolonged canals, two oceans which nature has separated; and by her proximity to the United States and to Europe, appears to have been destined by the Author of Nature as the centre and empire of the human family.The purpose of these boasts was to underscore the importance of the U.S. being the first to recognize its independence, to which Torres added warnings about the unstable politics of Mexico and Peru.

[67] Pedro José Gual, now the Colombian secretary of state and foreign relations, wrote to Bolívar that Torres deserved sole credit for the achievement.

His long exile from Colombia has tended to obscure him in diplomatic history compared to his contemporaries;[80] indeed his grave site was forgotten until rediscovered by historian Charles Lyon Chandler in 1924.

[83] Responding to an accusation by Spanish writer J. E. Casariego that Torres was a traitor to his native Spain, Nicolás García Samudio in 1941 called him a patriot, even the originator of the Monroe Doctrine[84]—though that specific claim has been met skeptically.

]The argument is quite unconvincing, if only because there is no reason to believe that a foreign envoy (and an unrecognized one, at that) could have played any important part in persuading Adams and Monroe to adopt an idea which had been anticipated by many persons in the United States, including statesmen of the first rank, during the past decade.