Economy of Iceland

[18] The 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis produced a decline in GDP and employment, which has since been reversed entirely by a recovery aided by a tourism boom starting in 2010.

[19] After a period of robust growth, Iceland's economy is slowing down according to an economic outlook for the years 2018–2020 published by Arion Research in April 2018.

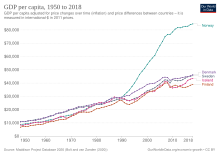

[21] In the 1990s Iceland undertook extensive free market reforms, which initially produced strong economic growth.

In 2007, Iceland topped the list of nations ranked by Human Development Index[23] and was one of the most egalitarian, according to the calculation provided by the Gini coefficient.

In the past, deposits of sulphur have been mined, and diatomite (skeletal algae) was extracted from Lake Mývatn until recently.

By far the largest of the many Icelandic hydroelectric power stations is Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant (690 MW) in the area north of Vatnajökull.

Iceland has explored the feasibility of exporting hydroelectric energy via submarine cable to mainland Europe and also actively seeks to expand its power-intensive industries, including aluminium and ferro-silicon smelting plants.

Recent geological research has improved the likelihood of Iceland having sizable off-shore oil reserves within its 200 mile economic zone in the seabed of the Jan Mayen area.

[30] In October 2017 the tourism sector directly employed around 26,800 people, with the total number of employees in the country being 186,900.

[26] The presence of abundant electrical power due to Iceland's geothermal and hydroelectric energy sources has led to the growth of the manufacturing sector.

There are currently three plants in operation with a total capacity of over 850,000 metric tons per year (t/yr) in 2019,[34] putting Iceland at 11th place among aluminium-producing nations worldwide.

Rio Tinto Alcan operates Iceland's first aluminium smelter (plant name: ISAL), in Straumsvík, near the town of Hafnarfjörður.

The second plant started production in 1998 and is operated by Norðurál, a wholly owned subsidiary of U.S.-based Century Aluminum Company.

[38] According to Alcoa, construction of Fjardaál entailed no human displacement, no impact on endangered species, and no danger to commercial fisheries; there will also be no significant effect on reindeer, bird and seal populations.

[39] However, the project drew considerable opposition from environmentalist groups such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, which called on Alcoa to abandon the plan to build Fjardaál.

[42] In 2006, Nordurál signed a memorandum of understanding with two Icelandic geothermal power producers, Hitaveita Suðurnesja and Orkuveita Reykjavíkur, to purchase electricity for its own aluminium reduction project in Helguvík.

[43] Fisheries and related sectors—in recent years labelled "the ocean cluster"—was the single most important part of the Icelandic economy (it has now been replaced by tourism) representing an overall contribution to GDP of 27.1% in 2011.

By contrast, aquaculture remains a very small industry in Iceland, employing only around 250 people for a production of 5,000 tonnes.

[46] Iceland is the second biggest fisheries nation in the North East Atlantic behind Norway, having overtaken the United Kingdom in the early 1990s.

[47] Iceland has been affected by a general decline in fishing yields in the Northeast Atlantic, with a one-way decrease of 18% from 2003 to 2009, although this trend appears to have been halted or reversed.

[citation needed] Cod remains the most important species harvested by Icelandic fisheries, with a total catch of 178,516 tonnes in 2010.

Subsequently, the stock showed signs of instability and quotas were reduced, leading to a decline in the catch to 87,121 tonnes in 2010.

All domestic trading in Icelandic stocks, bonds and mutual funds takes place on the ICEX.

Historically, investors tended to be reluctant to hold Icelandic bonds because of the persistence of high inflation and the volatility of the króna.

[citation needed] By the end of 2018, Bitcoin mining was expected to consume more electricity in Iceland than all the country's residents combined.

Other important exports include aluminium, ferro-silicon alloys, machinery and electronic equipment for the fishing industry, software, woollen goods.

It provides 40% of export income and employs 7.0% of the workforce; therefore, the state of the economy remains sensitive to world prices for fish products.

[52] When corrected for the dramatic depreciation of the Icelandic króna in 2008 (approximately 50% against the euro and US dollar), imports since the 2007 peak have been negative.

Under the agreement on a European Economic Area, effective January 1, 1994, there is basically free cross-border movement of capital, labor, goods, and services between Iceland, Norway, and the EU countries.