Many-sorted logic

Many-sorted logic can reflect formally our intention not to handle the universe as a homogeneous collection of objects, but to partition it in a way that is similar to types in typeful programming.

Both functional and assertive "parts of speech" in the language of the logic reflect this typeful partitioning of the universe, even on the syntax level: substitution and argument passing can be done only accordingly, respecting the "sorts".

There are various ways to formalize the intention mentioned above; a many-sorted logic is any package of information which fulfils it.

In most cases, the following are given: The domain of discourse of any structure of that signature is then fragmented into disjoint subsets, one for every sort.

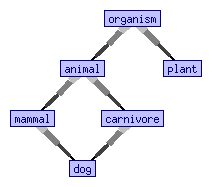

When reasoning about biological organisms, it is useful to distinguish two sorts:

makes sense, a similar function

Many-sorted logic allows one to have terms like

as syntactically ill-formed.

The algebraization of many-sorted logic is explained in an article by Caleiro and Gonçalves,[1] which generalizes abstract algebraic logic to the many-sorted case, but can also be used as introductory material.

While many-sorted logic requires two distinct sorts to have disjoint universe sets, order-sorted logic allows one sort

to be declared a subsort of another sort

In the above biology example, it is desirable to declare and so on; cf.

is required, a term of any subsort of

may be supplied instead (Liskov substitution principle).

For example, assuming a function declaration

is perfectly valid and has the sort

In order to supply the information that the mother of a dog is a dog in turn, another declaration

may be issued; this is called function overloading, similar to overloading in programming languages.

Order-sorted logic can be translated into unsorted logic, using a unary predicate

The reverse approach was successful in automated theorem proving: in 1985, Christoph Walther could solve a then benchmark problem by translating it into order-sorted logic, thereby boiling it down an order of magnitude, as many unary predicates turned into sorts.

[2] In order to incorporate order-sorted logic into a clause-based automated theorem prover, a corresponding order-sorted unification algorithm is necessary, which requires for any two declared sorts

Smolka generalized order-sorted logic to allow for parametric polymorphism.

[3][4] In his framework, subsort declarations are propagated to complex type expressions.

As a programming example, a parametric sort

being a type parameter as in a C++ template), and from a subsort declaration

is automatically inferred, meaning that each list of integers is also a list of floats.

Schmidt-Schauß generalized order-sorted logic to allow for term declarations.

[5] As an example, assuming subsort declarations

allows to declare a property of integer addition that could not be expressed by ordinary overloading.

Early papers on many-sorted logic include: