Maraapunisaurus

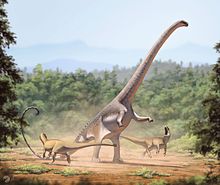

Maraapunisaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of western North America.

However, because the only fossil remains were lost at some point after being studied and described in the 1870s, evidence survived only in contemporary drawings and field notes.

[5][3] The holotype and only known specimen of Maraapunisaurus fragillimus was collected by Oramel William Lucas, shortly after he had been hired as a fossil collector by the renowned paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, in 1877.

Lucas discovered a partial vertebra (the neural arch including the spine) of a new sauropod species in Garden Park, north of Cañon City, Colorado, close to the quarry that yielded the first specimens of Camarasaurus.

[citation needed] The specific name was chosen to express that the fossil was "very fragile", referring to the delicateness of the bone produced by very thin laminae (vertebral ridges).

In 1902, Oliver Perry Hay hypercorrected the name to the Latin fragilissimus,[9] but such emendations are not allowed by the ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature).

Carpenter observed that the fossil bones known from the quarry would have been preserved in deeply weathered mudstone, which tends to crumble easily and fragment into small, irregular cubes.

[2] In 1994, an attempt was made to relocate the original quarry where the species and others had been found, using ground-penetrating radar to image bones still buried in the ground.

The attempt failed because the fossilized mudstone bones were the same density as the surrounding rock, making it impossible to differentiate between the two.

A study of the local topography also showed that the fossil-bearing rock strata were severely eroded, and probably were so when Lucas discovered M. fragillimus, suggesting that a majority of the skeleton had already disappeared when the vertebra was recovered.

They note that no comparably gigantic sauropod fossils have been discovered in the Morrison Formation or elsewhere, that 19th century paleontologists – including Cope himself – paid no attention to the size of fossil (even when it may have substantiated Cope's rule of size increase in animal lineages over time), and that typographical errors in his measurements – such as reporting vertebral measurements in meters rather than millimeters – undermine their reliability.

In addition to this, he pointed to the communication between Lucas and Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, a survey geologist, where the large size was repeated without question.

Later, in 1880, Lucas included specific mention of the specimen in his autobiography, noting "[w]hat a monster the animal must have been," refuting the idea that no attention was given to the importance of the vertebra.

Considering it to be a rebbachisaurid upon his re-examination, the species could not be referred to the genus Amphicoelias, and so he gave it a new generic name, Maraapunisaurus.

Overall, the revised length of the animal was around half of his earlier estimate, but still comparable to the other largest diplodocoids such as Supersaurus vivianae and Diplodocus hallorum.

Finally, he estimated the length of the toes of the hindfoot, and thus the imprint surface, at 1.36 metres (4.5 ft), resulting in a foot similar in size to the animal that must have made the giant sauropods tracks in Broome, Australia.

Weight is much more difficult to determine than length in sauropods, as the more complex equations needed are prone to greater margins of error based on smaller variations in the overall proportions of the animal.

In 2018, Carpenter concluded from a qualitative anatomical comparison that the species was a basal member of the Rebbachisauridae, and assigned it the new name Maraapunisaurus, after a Southern Ute word maraapuni meaning "huge".

Carpenter concluded that the Rebbachisauridae might have originated from that continent and only later spread to Europe; from there they would have invaded Africa and South America.

[2] In his 2006 re-evaluation, Carpenter examined the paleobiology of giant sauropods, including Maraapunisaurus, and addressed the question of why the group attained such a large size.

Carpenter cited several studies of giant mammalian herbivores, such as elephants and rhinoceros, which showed that larger size in plant-eating animals leads to greater efficiency in digesting food.

This is especially true of animals with a large number of 'fermentation chambers' along the intestine, which allow microbes to accumulate and ferment plant material, aiding digestion.

Carpenter argued that other benefits of large size, such as relative immunity from predators, lower energy expenditure, and longer life span, are probably secondary advantages.

Carpenter speculated that giant herbivores like Maraapunisaurus may have used the shade of the gallery forests to stay cool during the day, and done most of their feeding on the open savanna at night.