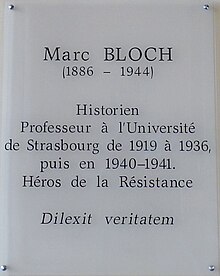

Marc Bloch

Bloch was a modernist in his historiographical approach, and repeatedly emphasised the importance of a multidisciplinary engagement towards history, particularly blending his research with that on geography, sociology and economics, which was his subject when he was offered a post at the University of Paris in 1936.

He had to leave Paris, and complained that the Nazi German authorities looted his apartment and stole his books; he was also persuaded by Febvre to relinquish his position on the editorial board of Annales.

As the first major display of political antisemitism in Europe, it was probably a formative event of Bloch's youth,[15][note 4] along with, more generally, the atmosphere of fin de siècle Paris.

[41] The historian Rees Davies notes that although Bloch served in the war with "considerable distinction",[4] it had come at the worst possible time both for his intellectual development and his study of medieval society.

[4] For the first time in his life, Bloch later wrote, he worked and lived alongside people he had never had close contact with before, such as shop workers and labourers,[21] with whom he developed a great camaraderie.

[47] He later remembered very little of the historical events he found himself in, writing only that his memories were[54][45] "a discontinuous series of images, vivid in themselves, but badly arranged, like a reel of motion picture film containing some large gaps and some reversals of certain scenes".

Thus, says Stephan R. Epstein of the London School of Economics, "Bloch's unrivalled knowledge of the European Middle Ages was ... built on and around the French University of Strasbourg's inherited German treasures".

Here he first expounded publicly his theories on total, comparative history:[43][note 11] "it was a compelling plea for breaking out of national barriers that circumscribed historical research, for jumping out of geographical frameworks, for escaping from a world of artificiality, for making both horizontal and vertical comparisons of societies, and for enlisting the assistance of other disciplines".

He was particularly influential on Bloch, who later said that Pirenne's approach should be the model for historians and that "at the time his country was fighting beside mine for justice and civilisation, wrote in captivity a history of Europe".

In a letter to the recruitment board written the same year, Bloch indicated that although he was not officially applying, he felt that "this kind of work (which he claimed to be alone in doing) deserves to have its place one day in our great foundation of free scientific research".

Sixty-seven divisions, lacking strong leadership, public support, and solid allies, waited almost three-quarters of a year to be attacked by a ruthless, stronger force.

[128] In November 1940 he received an offer of employment from The New School in New York, but he delayed his decision due to his reluctance to leave family members behind; it expired in July 1941 before he could obtain visas for his adult children.

[133] His university contacts included the local leaders of Combat and organisers of the Comité Général d'Etudes (an underground Conseil d'État[134]), René Courtin and Pierre-Henri Teitgen.

Facing the potential seizure or liquidation of Annales, Febvre insisted on continuing to publish it in Paris to ensure an international distribution and demanded that Bloch step down for the sake of preserving their project.

[142] The Polish social historian Bronisław Geremek suggests that this document hints at Bloch in some way foreseeing his death,[143] as he emphasised that nobody had the right to avoid fighting for their country.

[115] This was the catalyst for Bloch's decision to join the moderate republican Franc-Tireur movement (FT) in the French Resistance, led by Jean-Pierre Lévy [fr], which was being integrated by Jean Moulin into Mouvements unis de la Résistance (MUR), by March 1943.

[126] He sent his family away to Fougères (except for his daughter who worked in Limoges and for his two elder sons whom he helped cross the border to Francoist Spain[146]) and moved to Lyon to join the underground,[115] although he found this difficult because of his age.

[153] At the time, he was the acting head of the regional directory of the MUR for Rhône-Alpes,[154] tasked with preparing the uprising and seizure of power to coincide with the Allied landing (Jour-J),[147] and used the aliases "Maurice Blanchard" and "Narbonne".

[159] 'Chardon' was cleared of suspicion by Alban Vistel, the regional head of MUR whom Bloch was replacing due to sickness, in an investigation which found that two other members of the network ('Chatoux' of Combat and Madame Jacotot) were seen in a Gestapo car after their arrests.

[161][162] The minister of information and propaganda Philippe Henriot boasted afterwards of destroying "the capital of the Resistance" in Lyon,[161] and the German ambassador Otto Abetz telegraphed about Bloch's arrest to Berlin.

[114][163] As a key Resistance figure, he was interrogated and tortured daily in the Lyon Gestapo headquarters at the School of Military Health in avenue Berthelot by Klaus Barbie's men, suffering beatings, pneumonia from ice-baths, broken ribs and wrists.

[170][171] Eventually his personal effects were identified in September 1944 by his daughter Alice and sister-in-law Hélène Weill, who notified Febvre, and his death was officially announced on 1 November.

Examined through this lens as a quixotic idealist, Bloch is revealed as the undogmatic creator of a powerful – and perhaps ultimately unstable – method of historical innovation that can most accurately be described as quintessentially modern.

Much of his editorialising in Annales emphasised the importance of parallel evidence to be found in neighbouring fields of study, especially archaeology, ethnography, geography, literature, psychology, sociology, technology,[197] air photography, ecology, pollen analysis and statistics.

[194] According to Stirling, this posed a particular problem within French historiography when Bloch effectively had martyrdom bestowed upon him after the war, leading to much of his work being overshadowed by the last months of his life.

[192] His legacy has been further complicated by the fact that the second generation of Annalists led by Fernand Braudel has "co-opted his memory",[192][note 20] combining Bloch's academic work and Resistance involvement to create "a founding myth".

[212] The aspects of his life which made Bloch easy to beatify have been summed up by Henry Loyn as "Frenchman and Jew, scholar and soldier, staff officer and Resistance worker ... articulate on the present as well as the past".

For example, although he was a keen advocate for chronological precision and textual accuracy, his only major work in this area, a discussion of Osbert of Clare's Life of Edward the Confessor, was subsequently "seriously criticised"[126] by later experts in the field such as R. W. Southern and Frank Barlow;[4] Epstein later suggested Bloch was "a mediocre theoretician but an adept artisan of method".

[214] Colleagues who worked with him occasionally complained that Bloch's manner could be "cold, distant, and both timid and hypocritical"[207] due to the strong views he had held on the failure of the French education system.

For example, candidates Nicolas Sarkozy and Marine Le Pen both cited Bloch's lines from Strange Defeat: "there are two categories of Frenchmen who will never really grasp the significance of French history: those who refuse to be thrilled by the Consecration of our Kings at Reims, and those who can read unmoved the account of the Festival of Federation".