Maria Leopoldina of Austria

[1] With a deep Christian faith and a solid scientific and cultural background (which included international politics and notions of government) the Archduchess had been prepared from an early age to being a proper royal consort.

She was also adviser to Dom Pedro on important political decisions that reflected the future of the nation, such as the Dia do Fico and the subsequent opposition and disobedience to the Portuguese courts regarding the couple's return to Portugal.

[20] Muse and personal friend of the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, she was responsible for the intellectual formation of her stepdaughter, developing in Maria Leopoldina a taste for literature, nature and music by Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven.

She and her siblings were raised in accordance with the educational principles laid down by their grandfather, Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, who preached equality between men, treating everyone with courtesy, the need to practise charity, and above all, the sacrifice of their own desires for the needs of the State.

We must strive earnestly to be good".The study program for Maria Leopoldina and her siblings included subjects such as reading, writing, dance, drawing, painting, piano, riding, hunting, history, geography and music;[21] and in an advanced module, mathematics (arithmetic and geometry), literature, physics, singing and crafts.

The Marquis of Marialva made a guarantee that the Portuguese royal family was determined to return to the continent as soon as Brazil demonstrated that it had surely "escaped the flames of the wars of independence that were advancing in the Spanish colonies", thus obtaining Austrian consent to marriage.

Two ships were prepared, and in April 1817, scientists, painters, gardeners and a taxidermist, all with assistants, travelled to Rio de Janeiro ahead of Maria Leopoldina, who, in the meantime, studied the history and geography of her future home and learned Portuguese.

[31] "The culmination of the wedding ceremonies was reached in Vienna's Augarten where, on 1 June, Marialva, who had had few opportunities to reveal his nation's splendor, wealth and hospitality, gave a sumptuous reception for which she had made preparations during all winter.

She brought also an impressive household: court ladies, a chambermaid, a butler, six ladies-in-waiting, four pages, six Hungarian nobles, six Austrian guards, six chamberlains, a chief Almoner, a chaplain, a private secretary, a doctor, a performer, a mineralogist and her painting teacher.

[38] In addition, keeping with Portuguese tradition, the 18-year-old Dom Pedro not only had a string of amorous adventures behind him and was principally interested in horse racing and love affairs, but by the time of his marriage he was living as if in wedlock with French dancer Noemie Thierry, who was finally removed from the court by his father a month after Maria Leopoldina's arrival in Rio de Janeiro.

From 1824, due to the Brazilian campaign in Europe organized by Major Georg Anton Schäffer, the Germans arrived more numerous and settled again in Nova Friburgo and in the temperate regions of the provinces of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, where the colony of São Leopoldo was created in the new Royal Princess's honour.

Still in the 17th century, in the context of the Dutch occupation of northeastern Brazil, Prince John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen brought to Brazil a significant group of collaborators, among which we can mention Willem Piso, a doctor who came to study tropical diseases; Frans Post, famous painter, then in his early twenties; Albert Eckhout, also a painter; cartographer Cornelius Golijath; the astronomer Georg Marggraf, who, with Piso, would be the author of Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (Amsterdam, 1648), the first scientific work on Brazilian nature.

Therefore, in 1817, when the forthcoming announcement of the wedding of Maria Leopoldina and Dom Pedro, immediately was organized, under the auspices of the Austrian court, (but also integrated by Bavarian scientists) what would become the main scientific expedition into the unknown (for science) Brazilian lands.

[50] Prepared to maintain fidelity to the absolutist monarchy, Maria Leopoldina did not imagine that she would be Regent in the troubled moments that preceded the break with Portugal, nor that she would defend the Independence of Brazil even before Dom Pedro, in a clear attitude contrary to the education she received.

[51] Maria Leopoldina's determination to stay became even more staunch thanks to the support of José Bonifácio de Andrada, and educated man from São Paulo; with his help, she decisively convinced her husband that maintaining the territorial integrity of Brazil was only possible if they both remained there.

At the age of 24, Maria Leopoldina made a political decision that sentenced her to indefinite stay in America and would deprive her for the rest of her life from living near her father, siblings and other family members.

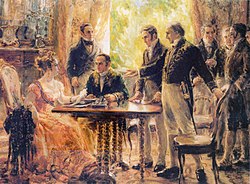

When her husband traveled to São Paulo in August 1822 to pacify politics (which culminated in the proclamation of Brazil's Independence in September), Maria Leopoldina was appointed as his official representative, that is, as Regent in his absence.

[60] Her status was confirmed with a document of investiture dated 13 August 1822 in which Dom Pedro appointing her head of the Council of State and Acting Princess-Regent of the Kingdom of Brazil, giving her complete authority to take any necessary political decisions during his absence.

Women's political awareness is also highlighted in the "Carta das senhoras baianas à sua alteza real dona Leopoldina", who congratulates the Princess-Regent for her part in the patriotic resolutions on behalf of her husband and the country.

The daughter that the Emperor had with his mistress in May 1824 (only three months later, the Empress also gave birth) was officially legitimized by him, named Isabel Maria de Alcântara Brasileira and granted the title of Duchess of Goiás with the style of Highness and the right to use the honorific "Dona".

".On the afternoon of the previous day (6 December), as reported by the same newspaper (and later confirmed by Father Sampaio's sermon) several processions accompanying "the Sacred Images of the respective churches" were destined for the Imperial Chapel.

According to Father Sampaio:[77] "Was never observed on the entrance of São Cristóvão such amount of people; the carriages were run over; everyone ran in tears, however, that in the city center the prayer processions revolved, with their images, and with the accompaniment of the whole clergy, either regular or secular.

[78] The version that Maria Leopoldina died as a result of the attacks on her during a tantrum of her husband, is a widespread theory corroborated by historians such as Gabriac, Carl Seidler, John Armitage and Isabel Lustosa.

Wanting to prove that the rumors about his extramarital relations and the bad climate between the Imperial couple were lies, Dom Pedro I decided to hold a large farewell reception where he demanded that both the Empress and his mistress the Marchioness of Santos appear together with him before the ecclesiastical and diplomatic dignitaries for the protocolary hand-kissing.

Although she is portrayed as a melancholic woman and humiliated by the scandals and extramarital relations of Dom Pedro I (representing her as the fragile link in the love triangle), the most recent historiography has claimed to Maria Leopoldina a less passive image in national history.

Maria Leopoldina's intellectual and political education, combined with her strong sense of duty and sacrifice on behalf of the State, were fundamental to Brazil, especially after King John VI, under Portuguese pressure, was forced to return to Lisbon.

In view of the fact that she was an Archduchess of Austria and member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine and who had been educated under an aristocratic and absolutist regime, Maria Leopoldina did not hesitate to defend ideals and more representative forms of government for Brazil, influenced by liberalism and constitutionalism.

Maria Leopoldina's arrival in Brazil fostered the beginning of German immigration to the country, first coming from the Swiss, settling in Rio de Janeiro and founding the city of Nova Friburgo.

The research of this mission resulted in the works Viagem pelo Brasil and Flora Brasiliensis, a compendium of approximately 20,000 pages with classification and illustration of thousands of species of native plants.

[9] "Regardless of the reasons that made Maria Leopoldina stay in Brazil, the Empress must be interpreted as a revolutionary woman because she was the first to make politics in the high sphere of Brazilian decisions", defends historian Paulo Rezzutti.