Pedro II of Brazil

His father's abrupt abdication and departure to Europe in 1831 left the five-year-old as emperor and led to a lonely childhood and adolescence, obliged to spend his time studying in preparation for rule.

His experiences with court intrigues and political disputes during this period greatly affected his later character; he grew into a man with a strong sense of duty and devotion toward his country and his people, yet increasingly resentful of his role as monarch.

The nation grew to be distinguished from its Hispanic neighbors on account of its political stability, freedom of speech, respect for civil rights, vibrant economic growth, and form of government—a functional representative parliamentary monarchy.

The Emperor established a reputation as a vigorous sponsor of learning, culture, and the sciences, and he won the respect and admiration of intellectuals such as Charles Darwin, Victor Hugo, and Friedrich Nietzsche, and was a friend to Richard Wagner, Louis Pasteur, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, among others.

The reign of Pedro II ended while he was highly regarded by the people and at the pinnacle of his popularity, and some of his accomplishments were reversed as Brazil slipped into a long period of weak governments, dictatorships, and constitutional and economic crises.

[12] Pedro I's desire to restore his daughter Maria II to her Portuguese throne, which had been usurped by his brother Miguel I, as well as his declining political position at home led to his abrupt abdication on 7 April 1831.

[37] Behind the scenes, a group of high-ranking palace servants and notable politicians led by Aureliano Coutinho (later Viscount of Sepetiba) became known as the "Courtier Faction" as they established influence over the young Emperor.

[45] In late 1845 and early 1846, the Emperor made a tour of Brazil's southern provinces, traveling through São Paulo (of which Paraná was a part at this time), Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul.

[59][60] Under the prime ministry of Honório Hermeto Carneiro Leão (then-Viscount and later Marquis of Paraná) the Emperor advanced his own ambitious program: the conciliação (conciliation) and melhoramentos (material developments).

[62] The active presence of Pedro II on the political scene was an important part of the government's structure, which also included the cabinet, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (the latter two formed the General Assembly).

[76] The most famous and enduring of these relationships involved Luísa Margarida Portugal de Barros, Countess of Barral, with whom he formed a romantic and intimate, though not adulterous, friendship after she was appointed governess to the emperor's daughters in November 1856.

[78] This is but one instance illustrating his dual identity: one who assiduously carried out his duty as emperor and another who considered the imperial office an unrewarding burden and who was happier in the worlds of literature and science.

For special occasions he would wear court dress, and he only appeared in full regalia with crown, mantle, and scepter twice each year at the opening and closing of the General Assembly.

[92][93] Subjects which interested Pedro II were wide-ranging, including anthropology, history, geography, geology, medicine, law, religious studies, philosophy, painting, sculpture, theater, music, chemistry, physics, astronomy, poetry, and technology among others.

[96] A passion for linguistics prompted him throughout his life to study new languages, and he was able to speak and write not only Portuguese but also Latin, French, German, English, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Chinese, Occitan, and Tupi.

[106] Using his civil list income, Pedro II provided scholarships for Brazilian students to study at universities, art schools, and conservatories of music in Europe.

[137] Aware of the anarchy in Rio Grande do Sul and the incapacity and incompetence of its military chiefs to resist the Paraguayan army, Pedro II decided to go to the front in person.

[158][159] The Emperor prevailed over a serious political crisis in July 1868 resulting from a quarrel between the cabinet and Luís Alves de Lima e Silva (then-Marques and later Duke of Caxias), the commander-in-chief of the Brazilian forces in Paraguay.

[162][163] Pedro II turned down the General Assembly's suggestion to erect an equestrian statue of him to commemorate the victory and chose instead to use the money to build elementary schools.

[171] With no constitutional authority to directly intervene to abolish slavery, the Emperor would need to use all his skills to convince, influence, and gather support among politicians to achieve his goal.

[190] As Catholicism was the state religion, the government exercised a great deal of control over Church affairs, paying clerical salaries, appointing parish priests, nominating bishops, ratifying papal bulls and overseeing seminaries.

[202] Pedro II arrived in New York City on 15 April 1876, and set out from there to travel throughout the country; going as far as San Francisco in the west, New Orleans in the south, Washington, D.C., and north to Toronto, Canada.

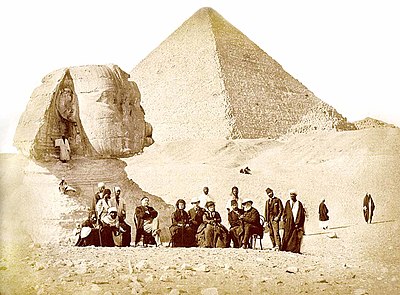

[204] He then crossed the Atlantic, where he visited Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Greece, the Holy Land, Egypt, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Britain, Ireland,[205] the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Portugal.

[215] Because of his increasing "indifference towards the fate of the regime" and his lack of action in support of the imperial system once it was challenged, historians have attributed the "prime, perhaps sole, responsibility" for the dissolution of the monarchy to the Emperor himself.

[31] These elder statesmen began to die off or retire from government until, by the 1880s, they had almost entirely been replaced by a newer generation of politicians who had no experience of the early years of Pedro II's reign.

[255] While the body was being prepared, a sealed package in the room was found, and next to it a message written by the Emperor himself: "It is soil from my country, I wish it to be placed in my coffin in case I die away from my fatherland.

[263][264] The journey continued on to the Church of São Vicente de Fora near Lisbon, where the body of Pedro was interred in the Royal Pantheon of the House of Braganza on 12 December.

There were demonstrations of sorrow throughout the country: shuttered business activity, flags displayed at half-staff, black armbands on clothes, death knells, religious ceremonies.

[271] The continued support for the deposed monarch is largely credited to a generally held and unextinguished belief that he was a truly "wise, benevolent, austere and honest ruler", said historian Ricardo Salles.

[272] The positive view of Pedro II, and nostalgia for his reign, only grew as the nation quickly fell into a series of economic and political crises which Brazilians attributed to the Emperor's overthrow.