Maria Sibylla Merian

Because of her careful observations and documentation of the metamorphosis of the butterfly, Merian is considered by David Attenborough to be among the more significant contributors to the field of entomology.

Her pioneering research in illustrating and describing the various stages of development, from egg to larva to pupa and finally to adult, dispelled the notion of spontaneous generation and established the idea that insects undergo distinct and predictable life cycles.

[9] Other women still-life painters, such as Merian's contemporary Margaretha de Heer, included insects in their floral pictures, but did not breed or study them.

From 1685 onward, Merian, her daughters, and her mother lived with the Labadist community, which had settled on the grounds of a stately home – Walt(h)a Castle – at Wieuwerd in Friesland.

In Amsterdam the same year, her daughter Johanna married Jakob Hendrik Herolt, a successful merchant in the Suriname trade, originally from Bacharach.

[10]: 166 In 1699, the city of Amsterdam granted Merian permission to travel to Suriname in South America, along with her younger daughter Dorothea Maria.

[17]: 211 In her subsequent publication on the expedition Merian criticised the actions of the colonial merchants, saying that "the people there have no desire to investigate anything like that; indeed they mocked me for seeking anything other than sugar in the country."

[20] Her daughter Dorothea published Erucarum Ortus Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis, a collection of her mother's work, after Merian's death.

While a handful of scholars had published empirical information on the insect, moth and butterfly life cycle, the widespread contemporary belief was that they were "born of mud" by spontaneous generation.

Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung – The Caterpillars' Marvellous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, was very popular in certain segments of high society as it was written in the vernacular, but her work was largely ignored by scientists of the time.

[21]: 36 The title page of her 1679 Caterpillars proudly proclaimed in German: "wherein by means of an entirely new invention the origin, food and development of caterpillars, worms, butterflies, moths, flies and other such little animals, including times, places and characteristics, for naturalists, artists, and gardeners, are diligently examined, briefly described, painted from nature, engraved in copper and published independently.

"[21]: 39 Jan Goedart had described and depicted the life stages of European moths and butterflies before her, but Merian's "invention" was the detailed study of species, their life-cycle and habitat.

[21]: 39 Goedart had not included eggs in his images of the life stages of European moths and butterflies, because he had believed that caterpillars were generated from water.

[21]: 40 While Merian's depiction of insects' life cycle was innovative in its accuracy, it was her observations on the interaction of organisms that are now regarded as a major contribution to the modern science of ecology.

[21]: 39 She also detailed the ways in which larvae formed their cocoons, the possible effects of climate on their metamorphosis and numbers, their mode of locomotion, and the fact that when caterpillars "have no food, they devour each other".

In general, only men received royal or government funding to travel in the colonies to find new species of plants and animals, make collections and work there, or settle.

She used Native American names to refer to the plants, which became used in Europe: I created the first classification for all the insects which had chrysalises, the daytime butterflies and the nighttime moths.

[7] Merian's drawings of plants, frogs,[26] snakes, spiders, iguanas, and tropical beetles are still collected today by amateurs all over the world.

[28]: 76 Metamorphosis and the tropical ants Merian documented were cited by the scientists René Antoine, August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof, Mark Catesby and George Edwards.

[17]: 212–213 When describing the pineapple Merian cited several standard works on natural history, which first had documented the fruit, such as Historia Naturalis Brasilae by Willem Piso and Georg Marggraf, Hortus Malabaricus by Hendrik van Rheede, and Medici Amstelodamensis by Caspar Commelin.

[17]: 216 A significant number of Merian's paintings combining a plant, caterpillar and butterfly are simply decorative, and make no attempt to describe the life cycle.

When she received a specimen from the London apothecary James Petiver she wrote to him that she was interested in "the formation, propagation, and metamorphosis of creatures, how one emerges from the other, and the nature of their diet.

Rumpf was a naturalist and in the course of his work for the Dutch East India Company had collected Indonesian shells, rocks, fossils and sea animals.

[28]: 77 The exotic specimens on display in Amsterdam may have inspired her to travel to Surinam, but only interrupted her study of European insects briefly.

[38] In another example, the printer of the 1730 edition of Surinam added plates using fictitious images of caterpillar life cycles that Merian did not originally include in the book and used for different, unscientific, purposes.

[28]: 88 Merian is considered a saint by the God's Gardeners, a fictional religious sect that is the focus of Margaret Atwood's 2009 novel The Year of the Flood.

In the late 1980s the Archiv imprint of the Polydor label issued a series of new recordings of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's piano works performed on period instruments, and featuring Merian's floral illustrations.

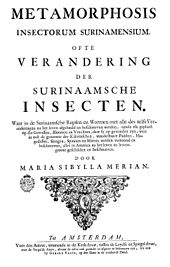

In 2016, Merian's Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium was re-published with updated scientific descriptions and, in June 2017, a symposium was held in her honour in Amsterdam.

[48][49][50] In March 2017, the Lloyd Library and Museum in Cincinnati, Ohio hosted "Off the Page", an exhibition rendering many of Merian's illustrations as 3D sculptures with preserved insects, plants, and taxidermy specimens.

[51][52] The Argentine black and white tegu (Salvator merianae), a type of large lizard, was named in honour of Merian after its discovery and classification.