Marine fungi

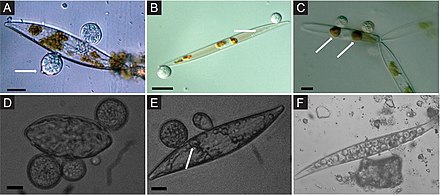

[4] It is impracticable to culture many of these fungi, but their nature can be investigated by examining seawater samples and undertaking rDNA analysis of the fungal material found.

Fungi can be found in niches ranging from ocean depths and coastal waters to mangrove swamps and estuaries with low salinity levels.

[2] Terrestrial fungi play critical roles in nutrient cycling and food webs and can shape macroorganism communities as parasites and mutualists.

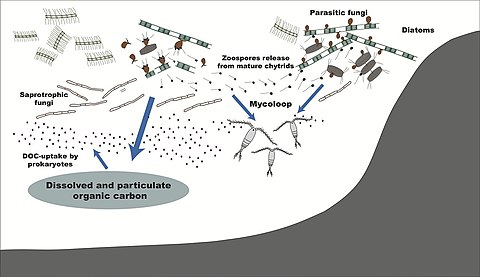

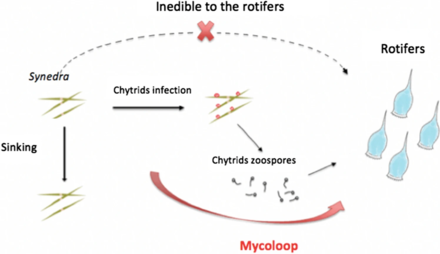

Fungi are hypothesized to contribute to phytoplankton population cycles and the biological carbon pump and are active in the chemistry of marine sediments.

Despite their varied roles, remarkably little is known about the diversity of this major branch of eukaryotic life in marine ecosystems or their ecological functions.

[6] Fungi represent a large and diverse group of microorganisms in microbiological communities in the marine environment and have an important role in nutrient cycling.

[9] Marine fungal species occur as saprobes, parasites, or symbionts and colonize a wide range of substrates, such as sponges, corals, mangroves, seagrasses and algae.

[5] Some marine fungi which have ventured into the sea from terrestrial habitats include species that burrow into sand grains, living in the pores.

[15] The earliest fossils possessing features typical of fungi date to the Paleoproterozoic era, some 2,400 million years ago (Ma).

[16] Other recent studies (2009) estimate the arrival of fungal organisms at about 760–1060 Ma on the basis of comparisons of the rate of evolution in closely related groups.

[17] For much of the Paleozoic Era (542–251 Ma), the fungi appear to have been aquatic and consisted of organisms similar to the extant Chytrids in having flagellum-bearing spores.

[21] The evolutionary adaptation from an aquatic to a terrestrial lifestyle necessitated a diversification of ecological strategies for obtaining nutrients, including parasitism, saprobism, and the development of mutualistic relationships such as mycorrhiza and lichenization.

[22] Recent (2009) studies suggest that the ancestral ecological state of the Ascomycota was saprobism, and that independent lichenization events have occurred multiple times.

[2] In one study, blocks of mangrove wood and pieces of driftwood of Avicennia alba, Bruguiera cylindrica and Rhizophora apiculata were examined to identify the lignicolous (wood-decaying) fungi they hosted.

It was surmised that this was because the salinity was lower in the estuaries and creeks where Nypa grew, and so it required a lesser degree of adaptation for the fungi to flourish there.

[46] Discovery of these fossils suggest that marine fungi developed symbiotic partnerships with photoautotrophs long before the evolution of vascular plants.

However a 2019 study concluded through age estimations obtained by time calibrated phylogenies, and absence of unambiguous fossil data that the origins of lichens postdate the evolution of vascular plants.

[58] The most commonly described fungi associated with algae belong to the Ascomycota and are represented by a wide diversity of genera such as Acremonium, Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Phoma, Penicillium, Trichoderma, Emericellopsis, Retrosium, Spathulospora, Pontogenia and Sigmoidea.

[33] Another fungus, Ascochyta salicorniae, found growing on seaweed is being investigated for its action against malaria,[63] a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals.

Similarly, a shrimp found in estuaries, Palaemon macrodactylis, has a symbiotic bacterium that produces 2,3-indolenedione, a substance that is also toxic to the oomycete Lagenidium callinectes.

Fungal infections in other cetaceans include Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Loboa loboi, Rhizopus sp., Aspergillus flavus, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Cladophialophora bantiana, Histoplasma capsulatum, Mucor sp., Sporothrix schenckii and Trichophyton sp.

Isolates showed that most subsurface fungal diversity was found between depths of 0 to 25 meters below the sea floor with Fusarium oxysporum and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa being the most prominent.

[67][68] Contrary to previous beliefs, deep subsurface marine fungi actively grow and germinate, with some studies showing increased growth rates under high hydrostatic pressures.

Though the methods by which marine fungi are able to survive the extreme conditions of the seafloor and below is largely unknown, Saccharomyces cerevisiae shines some light onto adaptations that make it possible.

Ocean crust fungi, like those found around hydrothermal vents, decompose organic matter, and play various roles in manganese and arsenic cycling.

[6] Sediment-bound marine fungi played a major role in breaking down oil spilled from the Deepwater Horizons disaster in 2010.

Chytridiomycota, the dominant parasitic fungal organism in Arctic waters, take advantage of phytoplankton blooms in brine channels caused by warming temperatures and increased light penetration through the ice.

[71] Marine fungi produce antiviral and antibacterial compounds as metabolites with upwards of 1,000 having realized and potential uses as anticancer, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory drugs.

[76] Mangrove-associated fungi have prominent antibacterial effects on several common pathogenic human bacteria including, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

High competition between organisms within mangrove niches lead to increases in antibacterial substances produced by these fungi as defensive agents.