Microbial loop

The term microbial loop was coined by Farooq Azam, Tom Fenchel et al.[1] in 1983 to include the role played by bacteria in the carbon and nutrient cycles of the marine environment.

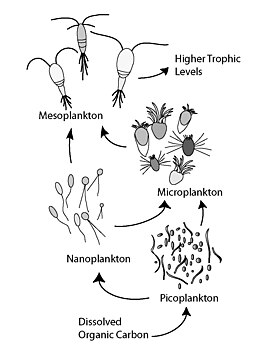

In general, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is introduced into the ocean environment from bacterial lysis, the leakage or exudation of fixed carbon from phytoplankton (e.g., mucilaginous exopolymer from diatoms), sudden cell senescence, sloppy feeding by zooplankton, the excretion of waste products by aquatic animals, or the breakdown or dissolution of organic particles from terrestrial plants and soils.

Prior to the discovery of the microbial loop, the classic view of marine food webs was one of a linear chain from phytoplankton to nekton.

However, the view of a marine pelagic food web was challenged during the 1970s and 1980s by Pomeroy and Azam, who suggested the alternative pathway of carbon flow from bacteria to protozoans to metazoans.

The term 'microbial loop' was introduced in this paper, which noted that the bacteria-consuming protists were in the same size class as phytoplankton and likely an important component of the diet of planktonic crustaceans.

[7] Stemming from this discovery, researchers observed the changing role of marine bacteria along a nutrient gradient from eutrophic to oligotrophic areas in the ocean.

[8] It has become clear that bacterial density is mainly controlled by the grazing activity of small protozoans and various taxonomic groups of flagellates.

Also, viral infection causes bacterial lysis, which release cell contents back into the dissolved organic matter (DOM) pool, lowering the overall efficiency of the microbial loop.

The magnitude of the efficiency of the microbial loop can be determined by measuring bacterial incorporation of radiolabeled substrates (such as tritiated thymidine or leucine).

Many planktonic bacteria are motile, using a flagellum to propagate, and chemotax to locate, move toward, and attach to a point source of dissolved organic matter (DOM) where fast growing cells digest all or part of the particle.

Therefore, the water column can be considered to some extent as a spatially organized place on a small scale rather than a completely mixed system.

If this is the case, the microbial loop can be extended by the pathway of direct transfer of dissolved organic matter (DOM) via abiotic microparticle formation to higher trophic levels.

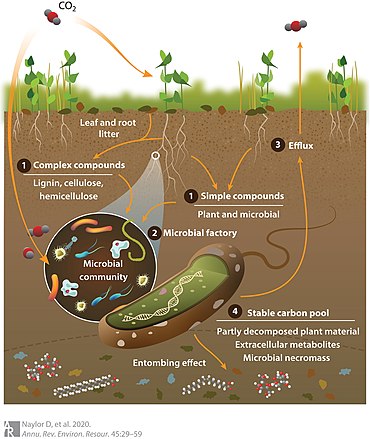

[15][10] The lack of information concerning the soil microbiome metabolic potential makes it particularly challenging to accurately account for the shifts in microbial activities that occur in response to environmental change.

The exact balance of carbon efflux versus persistence is a function of several factors, including aboveground plant community composition and root exudate profiles, environmental variables, and collective microbial phenotypes (i.e., the metaphenome).