Skylab 4

The mission began on November 16, 1973, with the launch of Gerald P. Carr, Edward Gibson, and William R. Pogue in an Apollo command and service module on a Saturn IB rocket from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida,[3] and lasted 84 days, one hour and 16 minutes.

The all-rookie astronaut crew arrived aboard Skylab to find that they had company – three figures dressed in flight suits.

[10] Things got off to a bad start after the crew attempted to hide Pogue's early space sickness from flight surgeons, a fact discovered by mission controllers after downloading onboard voice recordings.

Astronaut office chief Alan B. Shepard reprimanded them for this omission, saying they "had made a fairly serious error in judgement.

The crew's initial task of unloading and stowing the thousands of items needed for their lengthy mission also proved to be overwhelming.

NASA determined major contributing factors were a large number of new tasks added shortly before launch with little or no training, and searches for equipment out of place on the station.

[19][20][21] There was a radio conference to air frustrations[22] which led to the workload schedule being modified, and by the end of their mission the crew had completed even more work than originally planned.

Carr and Pogue alternately crewed controls, operating the sensing devices which measured and photographed selected features on the Earth's surface.

Gibson, who had trained as a scientist-astronaut, resigned from NASA in December 1974 to do research on Skylab solar physics data, as a senior staff scientist with The Aerospace Corporation of Los Angeles, California.

In order to catch up, they decided that only one crew member needed to be present for the daily briefing instead of all three, allowing the other two to complete ongoing tasks.

[26][27] Both Carr and Gibson stated that this event partially contributed to a discussion on December 30, 1973, in which the crew and ground control capsule communicator Richard H. Truly revisited the astronauts' schedule in light of their fatigue.

[28] While the lack of communications was unintentional, NASA still spent time to study its causes and effects as to avoid its replication in future missions.

On Skylab 4, one problem was that the crew was pushed even harder as they fell behind on their workload, creating an increasing level of stress.

[33] NASA was planning larger space stations but its budget shrank considerably after the Moon landings, and the Skylab orbital workshop was the only major execution of Apollo Applications projects.

Man-hours in space were, and continued to be into the 21st century, an expensive undertaking; a single day on Skylab was worth about $22.4 million in 2017 dollars, and thus any work stoppage was considered inappropriate[by whom?]

One of the first accounts reporting that a strike aboard Skylab had occurred was published in The New Yorker on August 22, 1976, by Henry S. F. Cooper, who claimed that the crew were alleged to have stopped working on December 28, 1973.

[26][28] NASA added that there may also have been confusion with a known ground equipment failure on December 25; this left them unable to track Skylab for one orbit, but the crew were notified of this issue ahead of time.

[26][27][44] Spaceflight history author David Hitt also disputed that the crew deliberately ended contact with mission control, in a book written with former astronauts Owen K. Garriott and Joseph P.

[52] Whereas Block II Apollo CSM had Kapton coated with aluminium and silicon monoxide, later Skylab modules had white paint for the sunward side.

[52] The Skylab 4 Command Module held the record for the longest single spaceflight for an American spacecraft for nearly 50 years until it was broken by Crew Dragon Resilience flying the SpaceX Crew-1 mission on February 7, 2021.

To commemorate the event, the four person crew of Crew-1 spoke live with Edward Gibson from the International Space Station.

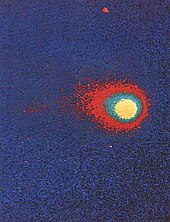

At the time of the flight, the astronauts issued the following description: "The symbols in the patch refer to the three major areas of investigation in the mission.

The hydrogen atom, as the basic building block of the universe, represents man's exploration of the physical world, his application of knowledge, and his development of technology.