Marisol Escobar

[3] She continued to create her artworks and returned to the limelight in the early 21st century, capped by a 2014 major retrospective show organized by the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art.

[6] Her father, Gustavo Hernandez Escobar, and her mother, Josefina, were from wealthy families and lived off assets from oil and real estate investments.

[6] Marisol additionally displayed talent in embroidery, spending at least three years embroidering the corner of a tablecloth (including going to school on Sundays in order to work).

During her teen years, she coped with the trauma of her mother's death by walking on her knees until they bled, keeping silent for long periods, and tying ropes tightly around her waist.

[8] After Josefina's death and Marisol's exit from the Long Island boarding school, the family traveled between New York and Caracas, Venezuela.

[14] According to Holly Williams, Marisol's sculptural works toyed with the prescribed social roles and restraints faced by women during this period through her depiction of the complexities of femininity as a perceived truth.

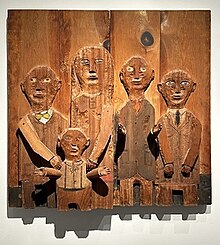

[15] Marisol's practice demonstrated a dynamic combination of folk art, dada, and surrealism – ultimately illustrating a keen psychological insight on contemporary life.

[17] Using an assemblage of plaster casts, wooden blocks, woodcarving, drawings, photography, paint, and pieces of contemporary clothing, Marisol effectively recognized their physical discontinuities.

[16] As Luce Irigaray noted in her book This Sex Which is Not One, "to play with mimesis is thus, for a woman, to try to recover the place of her exploitation by discourse, without allowing herself to be simply reduced to it.

It means to resubmit herself … to ideas about herself, that are elaborated in/by amasculine logic, but so as to make visible, by an effect of playful repetition what was supposed to remain invisible".

[26] Marisol further deconstructed the idea of true femininity in her sculptural grouping The Party (1965–1966), which featured a large number of figures adorned in found objects of the latest fashion.

[20] Through Marisol's theatric and satiric imitation, common signifiers of 'femininity' are explained as patriarchal logic established through a repetition of representation within the media.

[20] But, by incorporating casts of her own hands and expressional strokes in her work, Marisol combined symbols of the 'artist' identity celebrated throughout art history.

[30] De Gaulle's features were emphasized in order to create a caricature, by exaggerating his jowl, distancing his eyes, narrowing his mouth, and skewing his tie.

[30] His uniform, cast hand, and static carriage made the sculpture overtly asymmetrical to suggest the general public's concern for government correctness.

[26] For feminists her work was often perceived as reproducing tropes of femininity from an uncritical standpoint, therefore repeating modes of valorization they hoped to move past.

[35] In an article exploring yearbook illustrations of a very young Marisol, author Albert Boimes notes the often uncited shared influence between her work and other Pop artists.

was the way Grace Glueck titled her article in The New York Times in 1965:[11] "Silence was an integral part of Marisol's work and life.

[39] Curator Wendy Wick Reaves said that Escobar is "always using humor and wit to unsettle us, to take all of our expectations of what a sculptor should be and what a portrait should be and messing with them.

[15] She was one of many artists disregarded due to the existing modernist canon, which positioned her outside of the core of pop as the feminine opposite to her established male counterparts.

[46] Critical evaluation of Marisol's practice concluded that her feminine view was a reason to separate her from other Pop artists, as she offered sentimental satire rather than a deadpan attitude.

[48] Yet, Lippard primarily spoke of the ways in which Marisol's work differentiated from the intentions of Pop figureheads such as Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, and Donald Judd.

[44] Lippard defined a Pop artist as an impartial spectator of mass culture depicting modernity through parody, humor, and/or social commentary.

[44] As a female artist of color, critics distinguished Marisol from Pop as a 'wise primitive' due to the folk and childlike qualities within her sculptures.

[44] Unlike Pop artists of the period, Marisol's sculpture acted as a satiric criticism of contemporary life in which her presence was included in the representations of upper middle-class femininity.

[49] Simultaneously, by including her personal presence through photographs and molds, the artist illustrated a self-critique in connection to the human circumstances relevant to all living the "American dream".

[50] Marisol depicted the human vulnerability that was common to all subjects within a feminist critique and differentiated from the controlling male viewpoint of her Pop art associates.

[50] Instead of omitting her subjectivity as a woman of color, Marisol redefined female identity by making representations that made mockery of current stereotypes.

[15] Critical evaluation of Marisol's practice concluded that her feminine view was a reason to separate her from other Pop artists, as she offered sentimental satire rather than a deadpan attitude.

[53] In 2004, Marisol's work was featured in "MoMA at El Museo", an exhibition of Latin American artists held at the Museum of Modern Art.