Mark Sykes

Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 – 16 February 1919) was an English traveller, Conservative Party politician, and diplomatic advisor, particularly with regard to the Middle East at the time of the First World War.

Lady Sykes lived in London, and Mark divided his time between her home and his father's 34,000 acre (120 km2) East Riding of Yorkshire estates.

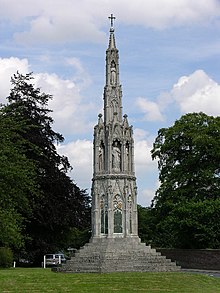

[2] Sledmere House "lay like a ducal demesne among the Wolds, approached by long straight roads and sheltered by belts of woodland, surrounded by large prosperous farms...ornamented with the heraldic triton of the Sykes family...the mighty four-square residence and the exquisite parish church.

[8] Sykes was sent abroad with the 5th Battalion of the Green Howards during the Second Boer War for two years, where he was engaged mostly in guard duty, but saw action on several occasions.

He made a friend of the Prime Minister, who went on to serve as Foreign Secretary during the First World War, when Sykes worked closely with him.

Transferred by Balfour, he served as honorary attaché to the British Embassy in Constantinople 1905–06, at which time he began a lifetime's interest in middle eastern affairs of state.

This is reflected in the Turkish Room he had installed in Sledmere House, using the noted Armenian ceramic artist David Ohannessian as designer.

The author H. G. Wells noted in the Appendix of his 1913 publication Little Wars, an early publication about the hobby of wargaming with miniature soldiers, that he had exchanged correspondence with "Colonel" Mark Sykes about how his hobby war game might be converted into a proper "Kriegspiel" as played by the British Army and be used as a training aid for young officers.

It was Sykes's intelligence that informed the Foreign Office that Turkey would fight alongside Germany – which Fitzgerald carried by letter to Kitchener.

[19] Sykes had long agreed with the traditional policy of British Conservatives in propping up Ottoman Turkey as a buffer against Russian expansion into the Mediterranean.

Liberal Party leader, William Ewart Gladstone, was much more critical of the Ottoman government, deploring its misgovernment and periodic slaughter of minorities, especially Christian ones.

[citation needed] Compounding Britain's difficulties, France sought to secure a Greater Syria, where there were significant minorities, that included Palestine.

Greece coveted historic Byzantine territories in Asia Minor and Thrace, claims that conflicted with those of Russia and Italy, as well as Turkey.

[citation needed] In mid-July 1915 the Emir Abdullah finally broke silence after 6 months to reply to the proposals which Sir Ronald Storrs had put to his father the Grand Sharif.

[citation needed] Sykes remained a purist who shunned democratic progress, instead vesting his energy in an indomitable Arab Spirit.

He was a champion of the Levantine tradition, of a mercantile trading empire, finding the progressive modernisation in the West totally unsuited to the desert kingdoms.

[citation needed] It was Sykes's special role to hammer out an agreement with Britain's most important ally, France, which was shouldering a disproportionate part of the effort against Germany in the First World War.

[citation needed] Late morning 16 December 1915 Sir Mark Sykes arrived at Downing street for a meeting to advise Prime Minister Asquith on the situation with the Ottoman Empire.

[24] Elected as Conservative MP in Hull in 1911, his maiden speech in November 1911 was about British foreign policy in the Middle East and North Africa.

[28] Lloyd George hated the corrupted Ottomans and could not wait to seize imperial power from them; while Balfour at the admiralty, was the only non-bellicose member.

It was reported on 16 August that Sykes was attending the Stockholm Conference as a paid up member of the Seamen & Firemen's Union, "but it cannot be known he carries their guarantee.

He alerted Hankey, the Cabinet Secretary, to General Maurice's agitation against the Prime Minister and Haig, as well as criticizing the King's part in the war.

Sykes was concerned that rumours were swirling around H. A. Gwynne, The Morning Post's editor, to the effect that Robertson was plotting with Asquith to bring back the old government.

[31] Sykes was convinced that the Jews held vast and sinister powers to manipulate world events and in March 1916 he wrote that with "great Jewry against us, there is no possible chance of getting the thing through [i.e winning the war]-it means optimism in Berlin, dumps in London, unease".

Moslem troops, Picot had mentioned were unreliable but Allenby would not be advised by any Political Officer who said the cross-border raids were upsetting the Arabs.

Diplomat and Sykes's biographer, Shane Leslie, wrote in 1923: From being the evangelist of Zionism during the war he had returned to Paris with feelings shocked by the intense bitterness which had been provoked in the Holy Land.

To Cardinal Gasquet he admitted the change of his views on Zionism, and that he was determined to qualify, guide and, if possible, save the dangerous situation which was rapidly arising.

At the conference, a junior diplomat present, Harold Nicolson, wrote in his diary the day after Sykes's death: "...It was due to his endless push and perseverance, to his enthusiasm and faith, that Arab nationalism and Zionism became two of the most successful of our war causes..."[37] He died in his room at the Hôtel Le Lotti near the Tuileries Garden on 16 February 1919, aged 39, a victim of the Spanish flu pandemic.

[38] Nahum Sokolow, a Russian Zionist colleague of Chaim Weizmann in Paris at this time, wrote that he "... fell as a hero at our side."

[38] In 2007, 88 years after Sir Mark Sykes died, all the living descendants gave their permission to exhume his body for scientific investigation headed by virologist John Oxford.