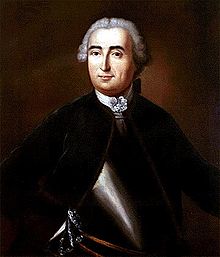

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm

[2] When the War of the Austrian Succession broke out in 1740, his regiment was stationed in France, so Montcalm, seeking action, took a position as an aide-de-camp to Philippe Charles de La Fare.

He took part in Marshal de Maillebois' Italian campaigns, where he was awarded the Order of Saint Louis in 1744[3] and taken prisoner in the 1746 Battle of Piacenza after receiving five sabre wounds while rallying his men.

When Montcalm returned to Fort Frontenac, he found a force of 3,500 men assembled, being regular French troops, Canadian militia, and Native Americans.

By the morning of August 13, the French had set up nine cannons and began to fire towards the fort while reinforcements surrounded the opposite side.

[7] 1,700 prisoners were taken, including 80 officers, as well as money, military correspondence, food provisions, guns, and boats, and the fort burnt and razed to the ground.

[9] Montcalm's first victory in North America came relatively quickly and easily, and signified to the British that the French now had a capable general heading their army.

Despite the victory, Montcalm held reservations concerning the offensive strategy employed by Vaudreuil, and questioned the military value of the Canadian militias.

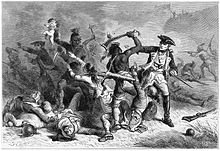

As the garrison left Fort William Henry, however, they were attacked by Montcalm's native allies, and around 200 of the 2,000 prisoners were killed, breaching the terms of surrender.

[6] Despite the relative insecurity of this particular fort and the overwhelming number of enemy troops, the French were able to hold the garrison due to a series of costly errors by the British general Abercrombie.

The French Minister of War nonetheless expressed his full support to Montcalm, confident that despite the odds, he would find a way to frustrate the enemy's plans, as he had done at Fort Carillon.

[12] This news, along with the threat of impending attack by the British, crushed Montcalm's spirit, who had lost all hope of holding the city in case of a siege.

[14] Montcalm, on many occasions, managed to repel attempted landings by the British forces, most notably at the Battle of Beauport, on 31 July 1759.

After spending the month of August ravaging the countryside,[14] the British would once again attempt a landing on September 13, this time at l'Anse au Foulons, catching the French off guard.

During the afternoon, the general drew on his last reserves of strength and signed his last official act as commander of the French army in Canada.

[18] In a letter addressed to General Wolfe, who unbeknownst to him had also fallen in battle, Montcalm attempted to surrender the city, despite the fact he did not hold the authority to do so.

[18] On October 11, 2001, the remains of Montcalm were removed from the Ursuline convent and placed into a newly built mausoleum in the cemetery of the Hôpital-Général de Québec.

The culture of the French metropolitan officer led Montcalm and others like him to see the Seven Years' War in terms of a defence of their own and their kingdom's honour, regardless of what it meant for New France.

[20] Conversely, the culture of the Canadian colonial officer led Vaudreuil and others like him to interpret the war in terms of a defence of the territorial integrity of New France and thus its very existence.

[24] Conversely, Vaudreuil was of the opinion that the war should be waged as based on established "colonial methods," which meant extending fortifications, consistently repelling British incursions, "defending the soil of our frontiers foot by foot against the enemy," fighting defensively, raiding extensively, and (most importantly) securing and relying heavily on Native participation.

"[27] The conflict between Montcalm and Vaudreuil would be largely solved or at least rendered irrelevant when, in 1758, the former was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, thus outranking the latter, and acquiring a virtually free hand in the determination of military strategy.