Marriage in the works of Jane Austen

Her main characters typically end up in marriages based on mutual affection, where love is balanced with practical concerns like social standing and financial stability.

While not directly criticizing the situation, Austen presents her view of a “good” marriage through her characters, offering a perspective on the different types of unions available to women.

[2] In the end, Austen’s heroines often find ideal marriages based on mutual respect and understanding, with partners who share both emotional and intellectual connections, regardless of social or financial status.

[9] In Pride and Prejudice, the narrator mentions Charlotte Lucas's brothers being relieved at the thought that they would no longer need to support her financially[10] if she remained unmarried.

[1] Marrying for financial security was a socially accepted norm, despite criticism from some writers like Mary Wollstonecraft, in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), and Jane West, in Letters to a Young Lady (1801), likened it to a form of "legalized prostitution.

"[19] In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet is shocked by her friend Charlotte Lucas's pragmatic approach to marriage, especially her decision to marry the foolish Mr.

John Dashwood, in Sense and Sensibility, expresses disappointment when his half-sister Elinor marries Edward Ferrars instead of Colonel Brandon, whose wealth and estate he had hoped to gain access to.

[29] This is evident in Mansfield Park, where Fanny Price, raised as a poor cousin by her wealthy uncle, is constantly reminded that she is not part of the Bertram family.

He had previously supported his eldest daughter’s choice to marry a wealthy but foolish man, seeing the match as a way to improve the family's position.

[31] In Emma, Frank Churchill's marriage to Jane Fairfax does not break social norms, but Harriet Smith, an illegitimate girl, gains respectability by marrying Robert Martin, a farmer.

In Pride and Prejudice, Darcy prevents Wickham from accessing his sister Georgiana's dowry, and Miss King's guardian takes her to Liverpool to protect her from a fortune-seeker.

In Sense and Sensibility, John Dashwood expresses his disappointment with his brother-in-law Robert Ferrars for secretly marrying the penniless Lucy Steele, suggesting that had the family known, they would have tried to prevent the marriage.

For example, Jane and Elizabeth Bennet help their younger sister Kitty improve her manners, and Mrs. Darcy contributes financially to assist the Wickhams.

[51][52] Jane Austen's novels focus on the transitional period in a young woman's life when she moves from her parents' home to that of her husband, as described in Fanny Burney's Evelina.

[55] However, if a woman sought happiness and wanted to preserve her moral integrity, she needed patience and courage, as Austen advised her niece, Fanny Knight, who was still single at twenty-five.

[54] There were many potential pitfalls in choosing a partner, and it often required strong resolve to decline a financially secure marriage, especially when the woman knew her future could be uncertain if she didn't marry.

Jane Austen often explores marriages based on first impressions, impulses, or youthful passion, showing how such unions can lead to dissatisfaction and difficulties for both the spouses and their children.

However, the couples are mismatched, as Elinor Dashwood observes “the strange unsuitableness which often existed between husband and wife.”[69] Sir John Middleton, a rural man with simple tastes,[70] shares little in common with his elegant but overwhelmed wife, except a mutual enjoyment of hosting guests.

[71] In Pride and Prejudice, Louisa Bingley’s dowry supports Mr. Hurst, a gentleman of little ambition, whose lifestyle revolves around eating, drinking, and playing cards.

[74] In Mansfield Park, Jane Austen portrays both reasonably happy marriages of convenience (like those of Sir Thomas and Lady Bertram, or the Grants) and less successful unions.

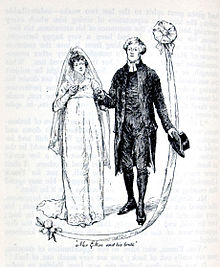

[95][96] Finally, characters like John Dashwood and Mr. Elton marry women who suit their ambitions, leading to relationships that, while based on convenience, appear superficially harmonious, similar to Charlotte Lucas’s practical marriage to Mr.

In the era’s conduct books, such as Hester Chapone's Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, there were warnings about marriages based solely on financial gain or social status.

Authors like Thomas Gisborne[61] and Mary Russell Mitford highlighted how women were often encouraged to marry for wealth or social standing,[note 14][101] but this mindset could undermine the possibility of forming genuine, lasting relationships.

Their partnership is marked by a balance of roles:[118] while the Admiral is unmethodical,[119] Mrs. Croft takes on tasks traditionally associated with men, showing practical skills and confidence in various situations.

For example, Jane Bennet and Charles Bingley share similar temperaments, while Elinor Dashwood and Edward Ferrars have aligned tastes and rational minds.

[135][136] Jane Austen, who lives in a pragmatic, mercantile society, never fails, for the sake of realism, to point out the means of existence on which not the happiness but the material comfort of her heroines depends.

While the girls often marry into their social class, with perfect, educated gentlemen as complex (intricate, as Elizabeth Bennet would say) and intelligent as themselves, whether landlords or clergymen, there are very few to whom she offers “fairy-tale” opulence.

Anne Elliot, who initially faces a mismatch by marrying a man of lower social rank, ultimately finds that her husband, Captain Wentworth, has earned his fortune and is respected in society.

Similarly, Catherine Morland meets Henry Tilney through mutual connections, and Jane and Elizabeth Bennet marry men who happen to be in their region for the hunting season.

In Emma, Captain Weston remarries after the death of his first wife, and Harriet Smith moves from being interested in Mr. Elton to Mr. Knightley before eventually accepting Robert Martin’s proposal.