Mary Wollstonecraft

[13] Wollstonecraft had envisioned living in a female utopia with Blood; they made plans to rent rooms together and support each other emotionally and financially, but this dream collapsed under economic realities.

[22] She learned French and German and translated texts,[23] most notably Of the Importance of Religious Opinions by Jacques Necker and Elements of Morality, for the Use of Children by Christian Gotthilf Salzmann.

Wollstonecraft's intellectual universe expanded during this time, not only from the reading that she did for her reviews but also from the company she kept: she attended Johnson's famous dinners and met the radical pamphleteer Thomas Paine and the philosopher William Godwin.

[29] After Fuseli's rejection, Wollstonecraft decided to travel to France to escape the humiliation of the incident, and to participate in the revolutionary events that she had just celebrated in her recent Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790).

[31] Against Burke's dismissal of the Third Estate as men of no account, Wollstonecraft wrote, "Time may show, that this obscure throng knew more of the human heart and of legislation than the profligates of rank, emasculated by hereditary effeminacy".

[31] About the events of 5–6 October 1789, when the royal family was marched from Versailles to Paris by a group of angry housewives, Burke praised Queen Marie Antoinette as a symbol of the refined elegance of the ancien régime, who was surrounded by "furies from hell, in the abused shape of the vilest of women".

[36] It was indicative that when Archibald Hamilton Rowan, the United Irishman, encountered her in the city in 1794 it was at a post-Terror festival in honour of the moderate revolutionary leader Mirabeau, who had been a great hero for Irish and English radicals before his death in April 1791.

[39] Having just written the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft was determined to put her ideas to the test, and in the stimulating intellectual atmosphere of the French Revolution, she attempted her most experimental romantic attachment yet: she met and fell passionately in love with Gilbert Imlay, an American adventurer.

For the same pride of office, the same desire of power are still visible; with this aggravation, that, fearing to return to obscurity, after having but just acquired a relish for distinction, each hero, or philosopher, for all are dubbed with these new titles, endeavors to make hay while the sun shines.

[42] Though Wollstonecraft disliked the former queen, she was troubled that the Jacobins would make Marie Antoinette's alleged perverse sexual acts one of the central reasons for the French people to hate her.

[39] In a March 1794 letter to her sister Everina, Wollstonecraft wrote: It is impossible for you to have any idea of the impression the sad scenes I have been a witness to have left on my mind ... death and misery, in every shape of terrour, haunts this devoted country—I certainly am glad that I came to France, because I never could have had else a just opinion of the most extraordinary event that has ever been recorded.

[46] Wollstonecraft was overjoyed; she wrote to a friend, "My little Girl begins to suck so MANFULLY that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the R[igh]ts of Woman" (emphasis hers).

[39] In 1793, the British government had begun a crackdown on radicals, suspending civil liberties, imposing drastic censorship, and trying for treason anyone suspected of sympathy with the revolution, which led Wollstonecraft to fear she would be imprisoned if she returned.

[51] The river Seine froze that winter, which made it impossible for ships to bring food and coal to Paris, leading to widespread starvation and deaths from the cold in the city.

[50] Against Burke's idealized portrait of Marie Antoinette as a noble victim of a mob, Wollstonecraft portrayed the queen as a femme fatale, a seductive, scheming and dangerous woman.

[61] Wollstonecraft considered her suicide attempt deeply rational, writing after her rescue, I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery.

[62]Gradually, Wollstonecraft returned to her literary life, becoming involved with Joseph Johnson's circle again, in particular with Mary Hays, Elizabeth Inchbald, and Sarah Siddons through William Godwin.

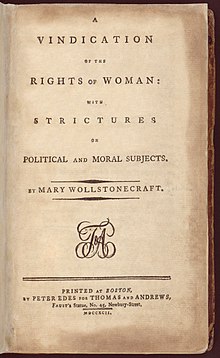

"[71] She was buried in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church, where her tombstone reads "Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: Born 27 April 1759: Died 10 September 1797.

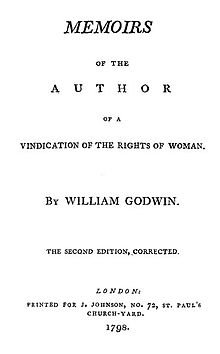

[78] After the devastating effect of Godwin's Memoirs, Wollstonecraft's reputation lay in tatters for nearly a century; she was pilloried by such writers as Maria Edgeworth, who patterned the "freakish" Harriet Freke in Belinda (1801) after her.

[81] In her 1799 pamphlet, Thoughts on the Condition of Women, Robinson describes Wollstonecraft as “an illustrious British female, (whose death has not been sufficiently lamented, but to whose genius posterity will render justice)”.

Fuller was an American journalist, critic, and women's rights activist who, like Wollstonecraft, had travelled to the Continent and had been involved in the struggle for reform (in this case the 1849 Roman Republic)—and she had a child by a man without marrying him.

[80] Millicent Garrett Fawcett, a suffragist and later president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, wrote the introduction to the centenary edition (i.e. 1892) of the Rights of Woman; it cleansed the memory of Wollstonecraft and claimed her as the foremother of the struggle for the vote.

Their fortunes reflected that of the second wave of the North American feminist movement itself; for example, in the early 1970s, six major biographies of Wollstonecraft were published that presented her "passionate life in apposition to [her] radical and rationalist agenda".

[121] Published in response to Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which was a defence of constitutional monarchy, aristocracy, and the Church of England, and an attack on Wollstonecraft's friend, the Rev.

In a famous passage in the Reflections, Burke had lamented: "I had thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her [Marie Antoinette] with insult.—But the age of chivalry is gone.

)[132] Wollstonecraft states that currently many women are silly and superficial (she refers to them, for example, as "spaniels" and "toys"[133]), but argues that this is not because of an innate deficiency of mind but rather because men have denied them access to education.

Wollstonecraft is intent on illustrating the limitations that women's deficient educations have placed on them; she writes: "Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.

Mary is itself a novel of sensibility and Wollstonecraft attempts to use the tropes of that genre to undermine sentimentalism itself, a philosophy she believed was damaging to women because it encouraged them to rely overmuch on their emotions.

The 25 letters cover a wide range of topics, from sociological reflections on Scandinavia and its peoples to philosophical questions regarding identity to musings on her relationship with Imlay (although he is not referred to by name in the text).

Reflecting the strong influence of Rousseau, Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark shares the themes of the French philosopher's Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782): "the search for the source of human happiness, the stoic rejection of material goods, the ecstatic embrace of nature, and the essential role of sentiment in understanding".