Mars Society

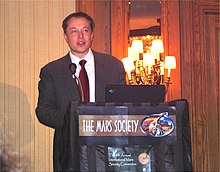

Many current and former Mars Society members are influential in the wider spaceflight community, such as Buzz Aldrin and Elon Musk.

Crew members perform simulated extravehicular activities, carry out research assignments and reside at the station on strictly rationed supplies.

Notable current and former members of the organization include Buzz Aldrin,[5] Elon Musk,[6]: 99–100 Gregory Benford[5] and James Cameron.

[7][4]: 347 The society is a member of the Alliance for Space Development[8] and has chapters in Australia, Canada, Europe, Japan, and many other countries.

[9]: 273 In the 2019 filing to the Internal Revenue Service, the Mars Society reported to receive around US$400,000 in donations per year.

As a consequence, they favored funding alternatives that are often impractical, such as sponsorship deals, private philanthropy, and Martian bonds (on the basis of future resources and profits).

[14]: 25 Most members belonging to the group were researchers and graduate students, which included Chris McKay, Penelope Boston, Tom Meyer, Carol Stoker, and Carter Emmart.

[4]: 352 On the second day of the convention, there was an intense debate about the ethics of Mars terraforming, which science writer Oliver Morton described as 'rancorous'.

On one side of the debate were Zubrin and a few other people, who championed that terraforming is the end goal of Mars colonization.

On the other side of the debate, the audience reminded them that for life on Mars, the act of terraforming will be similar to that of Native American genocide.

[6]: 112 In August 2001, Musk left the Mars Society after a meeting with its members and established a temporary foundation for his publicity projects,[20] despite pleas for collaboration from Zubrin.

[21] By April 2002, Musk had abandoned the temporary foundation entirely; instead, he founded SpaceX to build a low-cost rocket and invited aerospace engineers whom he had met at Mars Society-sponsored trips.

[24]: 74–75 From 2001 to 2005, Mars mission simulations in FMARS were around 2–8 weeks long and consisted of ten rotated crews.

The first four-month-long mock mission took place in 2007, which revealed cultural conflicts and inadequate coping strategies.

[6]: 99–100 The mission aimed to study the effect of Martian-level gravity on mice, with satellite construction supported by students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Georgia Tech.

Day from The Space Review, the MIT team won the debate by making specific and realistic arguments.

[29] In 2021, around a week before the first crewed New Shepard mission, Blue Origin donated US$1 million to the Mars Society and 18 other space-related organizations.

The Euro-MARS, operated by the Mars Society's European chapter, was intended to have three decks and more extensive facilities.

However, during transport from the United Kingdom to the deploying location at Krafla, Iceland, the Euro-MARS sustained irreparable damage.

[TMS 6] The station would replicate a spacecraft launching directly from the Earth's surface, featuring a mock propulsion module, heat shield and landing engines.

Around May and June each year, the three-day University Rover Challenge takes place in Utah's desert near the MDRS where teams compete in exploration tasks.

[34]: 63–72 MarsVR Project is a virtual reality program that simulates MDRS and terrain one square mile around the base.

[35] The exploration portion of MarsVR is free to download on Steam, however, the training part has an attached cost for the public.