Interstellar travel

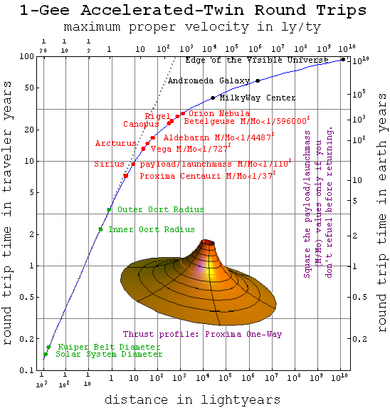

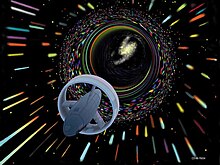

To travel between stars within a reasonable amount of time (decades or centuries), an interstellar spacecraft must reach a significant fraction of the speed of light, requiring enormous energy.

The benefits of interstellar travel include detailed surveys of habitable exoplanets and distant stars, comprehensive search for extraterrestrial intelligence and space colonization.

[9] In 2006, Andrew Kennedy calculated ideal departure dates for a trip to Barnard's Star using a more precise concept of the wait calculation where for a given destination and growth rate in propulsion capacity there is a departure point that overtakes earlier launches and will not be overtaken by later ones and concluded "an interstellar journey of 6 light years can best be made in about 635 years from now if growth continues at about 1.4% per annum", or approximately 2641 AD.

The following could be considered prime targets for interstellar missions:[9] Existing astronomical technology is capable of finding planetary systems around these objects, increasing their potential for exploration.

"Slow" interstellar missions (still fast by other standards) based on current and near-future propulsion technologies are associated with trip times starting from about several decades to thousands of years.

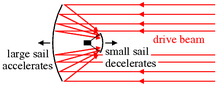

[23] As a near-term solution, small, laser-propelled interstellar probes, based on current CubeSat technology were proposed in the context of Project Dragonfly.

[18] In crewed missions, the duration of a slow interstellar journey presents a major obstacle and existing concepts deal with this problem in different ways.

[31] Interstellar space is not completely empty; it contains trillions of icy bodies ranging from small asteroids (Oort cloud) to possible rogue planets.

[32] If a spaceship could average 10 percent of light speed (and decelerate at the destination, for human crewed missions), this would be enough to reach Proxima Centauri in forty years.

The universe would appear contracted along the direction of travel to half the size it had when the ship was at rest; the distance between that star and the Sun would seem to be 16 light years as measured by the astronaut.

Very high specific power, the ratio of thrust to total vehicle mass, is required to reach interstellar targets within sub-century time-frames.

Thus, for interstellar rocket concepts of all technologies, a key engineering problem (seldom explicitly discussed) is limiting the heat transfer from the exhaust stream back into the vehicle.

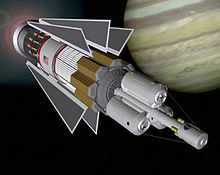

[42] Project Orion team member Freeman Dyson proposed in 1968 an interstellar spacecraft using nuclear pulse propulsion that used pure deuterium fusion detonations with a very high fuel-burnup fraction.

[43] Later studies indicate that the top cruise velocity that can theoretically be achieved by a Teller-Ulam thermonuclear unit powered Orion starship, assuming no fuel is saved for slowing back down, is about 8% to 10% of the speed of light (0.08-0.1c).

The concept of using a magnetic sail to decelerate the spacecraft as it approaches its destination has been discussed as an alternative to using propellant, this would allow the ship to travel near the maximum theoretical velocity.

[46] A current impediment to the development of any nuclear-explosion-powered spacecraft is the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which includes a prohibition on the detonation of any nuclear devices (even non-weapon based) in outer space.

Thus, although these concepts seem to offer the best (nearest-term) prospects for travel to the nearest stars within a (long) human lifetime, they still involve massive technological and engineering difficulties, which may turn out to be intractable for decades or centuries.

Although these are still far short of the requirements for interstellar travel on human timescales, the study seems to represent a reasonable benchmark towards what may be approachable within several decades, which is not impossibly beyond the current state-of-the-art.

[33] If energy resources and efficient production methods are found to make antimatter in the quantities required and store[49][50] it safely, it would be theoretically possible to reach speeds of several tens of percent that of light.

[53] Lenard and Andrews proposed using a base station laser to accelerate nuclear fuel pellets towards a Mini-Mag Orion spacecraft that ignites them for propulsion.

[citation needed] Yet the idea is attractive because the fuel would be collected en route (commensurate with the concept of energy harvesting), so the craft could theoretically accelerate to near the speed of light.

A theoretical idea for enabling interstellar travel is to propel a starship by creating an artificial black hole and using a parabolic reflector to reflect its Hawking radiation.

One potential method involves placing the hole at the focal point of a parabolic reflector attached to the ship, creating forward thrust.

A slightly easier, but less efficient method would involve simply absorbing all the gamma radiation heading towards the fore of the ship to push it onwards, and let the rest shoot out the back.

Twice as long as the Empire State Building is tall and assembled in-orbit, the spacecraft was part of a larger project preceded by interstellar probes and telescopic observation of target star systems.

In 1994, NASA and JPL cosponsored a "Workshop on Advanced Quantum/Relativity Theory Propulsion" to "establish and use new frames of reference for thinking about the faster-than-light (FTL) question".

[90] Geoffrey A. Landis of NASA's Glenn Research Center states that a laser-powered interstellar sail ship could possibly be launched within 50 years, using new methods of space travel.

[105] Brice N. Cassenti, an associate professor with the Department of Engineering and Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, stated that at least 100 times the total energy output of the entire world [in a given year] would be required to send a probe to the nearest star.

[105] Astrophysicist Sten Odenwald stated that the basic problem is that through intensive studies of thousands of detected exoplanets, most of the closest destinations within 50 light years do not yield Earth-like planets in the star's habitable zones.

One of the major stumbling blocks is having enough Onboard Spares & Repairs facilities for such a lengthy time journey assuming all other considerations are solved, without access to all the resources available on Earth.