Martin Luther and antisemitism

These changed dramatically from his early career, where he showed concern for the plight of European Jews, to his later years, when embittered by his failure to convert them to Christianity, he became outspokenly antisemitic in his statements and writings.

[citation needed] Reuchlin had successfully prevented the Holy Roman Empire from burning Jewish books but was racked by heresy proceedings as a result.

In August 1536 Luther's prince, Elector of Saxony John Frederick, issued a mandate that prohibited Jews from inhabiting, engaging in business in, or passing through his realm.

"[7] Josel of Rosheim, who tried to help the Jews of Saxony, wrote in his memoir that their situation was "due to that priest whose name was Martin Luther — may his body and soul be bound up in hell!!

"[8] Robert Michael, Professor Emeritus of European History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth writes that Josel asked the city of Strasbourg to forbid the sale of Luther's anti-Jewish works; they refused initially, but relented when a Lutheran pastor in Hochfelden argued in a sermon that his parishioners should murder Jews.

Offer them the Christian faith that they would accept the Messiah, who is even their cousin and has been born of their flesh and blood; and is rightly Abraham's Seed, of which they boast.

[30] According to Michael, Luther's work acquired the status of Scripture within Germany, and he became the most widely read author of his generation, in part because of the coarse and passionate nature of the writing.

[31] The prevailing view[32] among historians is that Luther's anti-Jewish rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany,[33] and in the 1930s and 1940s provided an ideal foundation for the Nazi Party's attacks on Jews.

"[36] Christopher J. Probst, in his book Demonizing the Jews: Luther and the Protestant Church in Nazi Germany (2012), shows that a large number of German Protestant clergy and theologians during the Nazi Third Reich used Luther's hostile publications towards the Jews and their Jewish religion to justify at least in part the anti-Semitic policies of the National Socialists.

"[44] Paul Halsall argues that Luther's views had a part in laying the groundwork for the racial European antisemitism of the nineteenth century.

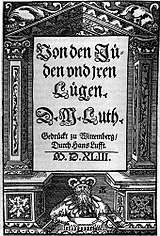

"[45] In his Lutheran Quarterly article, Wallmann argued that Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies, Against the Sabbabitarians, and Vom Schem Hamphoras were largely ignored by antisemites of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

He contended that Johann Andreas Eisenmenger and his Judaism Unmasked, published posthumously in 1711, was "a major source of evidence for the anti-Semites of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries" and "cast Luther's anti-Jewish writings into obscurity".

The prevailing scholarly view[47] since the Second World War is that the treatise exercised a major and persistent influence on Germany's attitude toward its Jewish citizens in the centuries between the Reformation and the Holocaust.

Hitler's Education Minister, Bernhard Rust, was quoted by the Völkischer Beobachter as saying: "Since Martin Luther closed his eyes, no such son of our people has appeared again.

"Through his acts and his spiritual attitude, he began the fight which we will wage today; with Luther, the revolution of German blood and feeling against alien elements of the Volk was begun.

"[61] William Nichols, Professor of Religious Studies, recounts, "At his trial in Nuremberg after the Second World War, Julius Streicher, the notorious Nazi propagandist, editor of the scurrilous antisemitic weekly Der Stürmer, argued that if he should stand there and be arraigned on such charges, so should Martin Luther.

"[62] It was Luther's expression "The Jews are our misfortune" that centuries later would be repeated by Heinrich von Treitschke and appear as a motto on the front page of Julius Streicher's Der Stürmer.

Richard Steigmann-Gall writes in his 2003 book The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945: The leadership of the Protestant League espoused a similar view.

Promising that the celebration of Luther's birthday would not turn into a confessional affair, Fahrenhorst invited Hitler to become the official patron of the Luthertag.

'"[69] Bainton's view is later echoed by James M. Kittelson writing about Luther's correspondence with Jewish scholar Josel of Rosheim: "There was no anti-Semitism in this response.

[76] Waite cites Wilhelm Röpke, writing after Hitler's Holocaust, who concluded that "without any question, Lutheranism influenced the political, spiritual and social history of Germany in a way that, after careful consideration of everything, can be described only as fateful.

"[79] He observes, [Luther's] opposition to the Jews, which ultimately was regarded as irreconcilable, was in its nucleus of a religious and theological nature that had to do with belief in Christ and justification, and it was associated with the understanding of the people of God and the interpretation of the Old Testament.

Luther's animosity toward the Jews cannot be interpreted either in a psychological way as a pathological hatred or in a political way as an extension of the anti-Judaism of the territorial princes.

But he certainly demanded that measures provided in the laws against heretics be employed to expel the Jews—similarly to their use against the Anabaptists—because, in view of the Jewish polemics against Christ, he saw no possibilities for religious coexistence.

Nevertheless, his misguided agitation had the evil result that Luther fatefully became one of the "church fathers" of anti-Semitism and thus provided material for the modern hatred of the Jews, cloaking it with the authority of the Reformer.

[82] Michael Berenbaum writes that Luther's reliance on the Bible as the sole source of Christian authority fed his later fury toward Jews over their rejection of Jesus as the Messiah.

He expressed concern for the poor conditions in which they were forced to live and insisted that anyone denying that Jesus was born a Jew was committing heresy.

[93] The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, in an essay on Lutheran-Jewish relations, observed that "Over the years, Luther's anti-Jewish writings have continued to be reproduced in pamphlets and other works by neo-Nazi and antisemitic groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan.

"[94] Writing in the Lutheran Quarterly in 1987, Dr. Johannes Wallmann stated: The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Protestant anti-Judaism and modern racially oriented anti-Semitism, is at present wide-spread in the literature; since the Second World War it has understandably become the prevailing opinion.

We reject this violent invective as did many of his companions in the sixteenth century, and we are moved to deep and abiding sorrow at its tragic effects on later generations of Jews."