St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The massacre began in the night of 23–24 August 1572, the eve of the Feast of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, two days after the attempted assassination of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots.

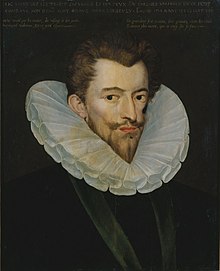

The strongly Catholic Guise family was out of favour at the French court; the Huguenot leader, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, was readmitted into the king's council in September 1571.

This intervention threatened to involve France in that war; many Catholics believed that Coligny had again persuaded the king to intervene on the side of the Dutch,[15] as he had managed to do the previous October, before Catherine had got the decision reversed.

Like Coligny, most potential candidates for elimination were accompanied by groups of gentlemen who served as staff and bodyguards, so murdering them would also have involved killing their retainers as a necessity.

That was interpreted by the Parisians as a sign of divine blessing and approval to these multiple murders,[22] and that night, a group led by Guise in person dragged Admiral Coligny from his bed, killed him, and threw his body out of a window.

According to the contemporary French historian Jacques Auguste de Thou, one of Coligny's murderers was struck by how calmly he accepted his fate, and remarked that "he never saw anyone less afraid in so great a peril, nor die more steadfastly".

Holt concludes that "while the general massacre might have been prevented, there is no evidence that it was intended by any of the elites at court", listing a number of cases where Catholic courtiers intervened to save individual Protestants who were not in the leadership.

[25] Recent research by Jérémie Foa, investigating the prosopography suggests that the massacres were carried by a group of militants who had already made out lists of Protestants deserving extermination, and the mass of the population, whether approving or disapproving, were not directly involved.

[26] The two leading Huguenots, Henry of Navarre and his cousin the Prince of Condé (respectively aged 19 and 20), were spared as they pledged to convert to Catholicism; both would eventually renounce their conversions when they managed to escape Paris.

[37] It has been claimed that the Huguenot community represented as much as 10% of the French population on the eve of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, declining to 7–8% by the end of the 16th century, and further after heavy persecution began once again during the reign of Louis XIV, culminating with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Estimates of the number that perished in the massacres have varied from 2,000 by a Roman Catholic apologist to 70,000 by the contemporary Huguenot Maximilien de Béthune, who himself barely escaped death.

[50] The pope ordered a Te Deum to be sung as a special thanksgiving (a practice continued for many years after) and had a medal struck with the motto Ugonottorum strages 1572 (Latin: "Overthrow (or slaughter) of the Huguenots 1572") showing an angel bearing a cross and a sword before which are the felled Protestants.

[51] Pope Gregory XIII also commissioned the artist Giorgio Vasari to paint three frescos in the Sala Regia depicting the wounding of Coligny, his death, and Charles IX before Parliament, matching those commemorating the defeat of the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto (1571).

[57] Protestant countries were horrified at the events, and only the concentrated efforts of Catherine's ambassadors, including a special mission by Gondi, prevented the collapse of her policy of remaining on good terms with them.

[69] The most extreme of these writers was Camilo Capilupi, a papal secretary, whose work insisted that the whole series of events since 1570 had been a masterly plan conceived by Charles IX, and carried through by frequently misleading his mother and ministers as to his true intentions.

[70] It was in this context that the massacre came to be seen as a product of Machiavellianism, a view greatly influenced by the Huguenot Innocent Gentillet, who published his Discours contre Machievel in 1576, which was printed in ten editions in three languages over the next four years.

The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913 was still ready to endorse a version of this view, describing the massacres as "an entirely political act committed in the name of the immoral principles of Machiavellianism" and blaming "the pagan theories of a certain raison d'état according to which the end justified the means".

[49] The French 18th-century historian Louis-Pierre Anquetil, in his Esprit de la Ligue of 1767, was among the first to begin impartial historical investigation, emphasising the lack of premeditation (before the attempt on Coligny) in the massacre and that Catholic mob violence had a history of uncontrollable escalation.

Despite the firm opposition of the Queen Mother and the King, Anjou, Lieutenant General of the Kingdom, present at this meeting of the council, could see a good occasion to make a name for himself with the government.

[citation needed] The Parisian St. Bartholomew's Day massacre resulted from this conjunction of interests, and this offers a much better explanation as to why the men of the Duke of Anjou acted in the name of the Lieutenant General of the Kingdom, consistent with the thinking of the time, rather than in the name of the King.

Initially the coup d'état of the duke of Anjou was a success, but Catherine de' Medici went out of her way to deprive him from any power in France: she sent him with the royal army to remain in front of La Rochelle and then had him elected King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Thus, some modern historians have stressed the critical and incendiary role that militant preachers played in shaping ordinary lay beliefs, both Catholic and Protestant.

Another historian Mack P. Holt, Professor at George Mason University, agrees that Vigor, "the best known preacher in Paris", preached sermons that were full of references to the evils that would befall the capital should the Protestants seize control.

[86] This view is also partly supported by Cunningham and Grell (2000) who explained that "militant sermons by priests such as Simon Vigor served to raise the religious and eschatological temperature on the eve of the Massacre".

[95] He concludes that the historical importance of the Massacre "lies not so much in the appalling tragedies involved as their demonstration of the power of sectarian passion to break down the barriers of civilisation, community and accepted morality".

According to Reuters and the Associated Press, at a late-night vigil, with the hundreds of thousands of young people who were in Paris for the celebrations, he made the following comments: "On the eve of Aug. 24, we cannot forget the sad massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day, an event of very obscure causes in the political and religious history of France.

"[98] The Elizabethan dramatist Christopher Marlowe knew the story well from the Huguenot literature translated into English, and probably from French refugees who had sought refuge in his native Canterbury.

[100] The story was fictionalised by Prosper Mérimée in his A Chronicle of the Reign of Charles IX (1829), and by Alexandre Dumas, père in La Reine Margot, an 1845 novel that fills in the history as it was then seen with romance and adventure.

Incidental characters include Henri of Navarre, Marguerite de Valois (Constance Talmadge), Admiral Coligny (Joseph Henabery), and the Duke of Anjou, who is portrayed as homosexual.

Several chapters depict in great detail the massacre and the events leading up to it, with the book's protagonists getting some warning in advance and making enormous but futile efforts to avert it.