Mastitis

Light cases of mastitis are often called breast engorgement; the distinction is overlapping and possibly arbitrary or subject to regional variations.

The term nonpuerperal mastitis describes inflammatory lesions of the breast occurring unrelated to pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Keratinizing squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts may play a similar[clarification needed] role in the pathogenesis of nonpuerperal subareolar abscess.

It has been shown that types and amounts of potentially pathogenic bacteria in breast milk are not correlated to the severity of symptoms.

[17] It has also been suggested that blocked milk ducts can occur as a result of pressure on the breast, such as tight-fitting clothing or an over-restrictive bra, although there is sparse evidence for this supposition.

There is a possibility that infants carrying infectious pathogens in their noses can infect their mothers;[18] the clinical significance of this finding is still unknown.

Mastitis can also develop due to contamination of a breast implant or any other foreign body, for example after nipple piercing.

[21] Women with diabetes, chronic illness, AIDS, or an impaired immune system may be more susceptible to the development of mastitis.

[8] Recent research suggests that infectious pathogens play a much smaller role in the pathogenesis than was commonly assumed only a few years ago.

In cases of infectious mastitis, cultures may be needed in order to determine what type of organism is causing the infection.

Some women who experience pain or other symptoms when breastfeeding, but who have no detectable signs of mastitis, may have a sensory processing disorder, postpartum depression, perinatal anxiety, dysphoric milk ejection reflex, an involuntary aversion to breastfeeding, or other mental health problems.

Only full resolution of symptoms and careful examination are sufficient to exclude the diagnosis of breast cancer.

[citation needed] Mastitis does however cause great difficulties in diagnosis of breast cancer.

Because of the very short time between presentation of mastitis and breast cancer in this study it is considered very unlikely that the inflammation had any substantial role in carcinogenesis, rather it would appear that some precancerous lesions may increase the risk of inflammation (hyperplasia causing duct obstruction, hypersensitivity to cytokines or hormones) or the lesions may have common predisposing factors.

Case reports show that inflammatory breast cancer symptoms can flare up following injury or inflammation making it even more likely to be mistaken for mastitis.

Symptoms are also known to partially respond to progesterone and antibiotics, reaction to other common medications can not be ruled out at this point.

[28] It may reduce the feeling of being full or swollen in the short term, at the cost of triggering milk oversupply, which can cause a mastitis recurrence in the coming days and weeks.

[28] For breastfeeding women with breast engorgement or light mastitis, using a warm compress may be comfortable.

[28] However, by increasing blood flow to the area, warm compresses make the symptoms worse for other women.

[28] The shape of swelling in a specific spot may make people suppose that the breasts contain simple tubes, and that one has become plugged.

However, milk ducts are not simple tubes, and their interconnected anatomy makes it impossible for them to actually become plugged.

[28] Breastfeeding at a normal level may provide temporary relief from the swelling without triggering milk oversupply.

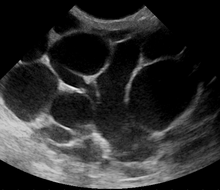

At follow-up, a mammography is performed if the condition has resolved; otherwise the ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration with lavage and microbiological analysis is repeated.

[47] If three to five aspirations still do not resolve the condition, percutaneous drainage in combination with placement of an indwelling catheter is indicated, and only if several attempts at ultrasound-guided drainage fail, surgical resection of the inflamed lactiferous ducts (preferably performed after the acute episode is over).

[52] Most efforts to prevent mastitis in breastfeeding women are believed to be ineffective or have a relatively small effect.

[37] Possibly effective prevention measures include taking probiotics, breast massage, and low-frequency pulse treatment.

[37] Ineffective methods included prophylactic antibiotics, topical treatments (mastitis is inflammation deep in the breast, so treating the skin is irrelevant[28]), specialist breastfeeding education, and anti‐secretory factor‐inducing cereal.

[37] Neither the presence of a fever nor the severity of symptoms at presentation do not predict outcome; women with sore or damaged nipples may need special attention.

Lighter cases of puerperal mastitis, appearing a few days after birth, are often called breast engorgement.

In this article, mastitis is used in the original sense of the definition as inflammation of the breast, with additional qualifiers where appropriate.