Maternal deprivation

Maternal deprivation is a scientific term summarising the early work of psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby on the effects of separating infants and young children from their mother (or primary caregiver).

The publication was also highly controversial with, amongst others, psychoanalysts, psychologists and learning theorists, and sparked significant debate and research on the issue of children's early relationships.

[6] Bowlby claimed to have made good the "deficiencies of the data and the lack of theory to link alleged cause and effect" in Maternal Care and Mental Health in his later work Attachment and Loss published between 1969 and 1980.

In the 19th century, French society bureaucratised a system in which infants were breast-fed at the homes of foster mothers, returning to the biological family after weaning, and no concern was evinced at the possible effect of this double separation on the child.

Following Freud's early speculations about infant experience with the mother, Otto Rank suggested a powerful role in personality development for birth trauma.

Not long after Rank's introduction of this idea, Ian Suttie, a British physician whose early death limited his influence, suggested that the child's basic need is for mother-love, and his greatest anxiety is that such love will be lost.

[9][10] In the 1930s, David Levy noted a phenomenon he called "primary affect hunger" in children removed very early from their mothers and brought up in institutions and multiple foster homes.

[11] A few psychiatrists, psychologists and paediatricians were also concerned by the high mortality rate in hospitals and institutions obsessed with sterility to the detriment of any human or nurturing contact with babies.

[12] In a series of studies published in the 1930s, psychologist Bill Goldfarb noted not only deficits in the ability to form relationships, but also in the IQ of institutionalised children as compared to a matched group in foster care.

There were many problematic parental behaviours in the samples but Bowlby was looking at one environmental factor that was easy to document, namely prolonged early separations of child and mother.

Controlling for various factors including income, stability, and parenting style, the study found increased aggressiveness at ages 3 and 5 in separated infants, but it did not find other cognitive impairment.

These authors were mainly unaware of each other's work, and Bowlby was able to draw together the findings and highlight the similarities described, despite the variety of methods used, ranging from direct observation to retrospective analysis to comparison groups.

Bowlby tackled not only institutional and hospital care, but also policies of removing children from "unwed mothers" and untidy and physically neglected homes, and lack of support for families in difficulties.

He stated, "It is this complex rich and rewarding relationship with the mother in the early years, varied in countless ways by relations with the father and with siblings, that child psychiatrists and many others now believe to underlie the development of character and mental health.

[34] Bowlby's theory sparked considerable interest and controversy in the nature of early relationships and gave a strong impetus to what Mary Ainsworth described as a "great body of research" in what was perceived as an extremely difficult and complex area.

In addition, views that he had already expressed about the importance of a child's real life experiences and relationship with carers had been met by "sheer incredulity" by colleagues before World War II.

Bowlby and his colleagues were pioneers of the view that studies involving direct observation of infants and children were not merely of interest but were essential to the advancement of science in this area.

[35] Researchers have for years studied depression, alcoholism, aggression, maternal-infant bonding and other conditions and phenomena in nonhuman primates and other laboratory animals using an experimental maternal deprivation paradigm.

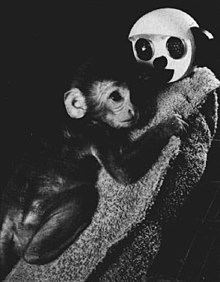

[36] Most influentially, Harry Harlow would, in the mid-1950s, begin raising infant monkeys in his University of Wisconsin–Madison laboratory in total or partial isolation and with inanimate surrogate mothers in an attempt to study maternal-infant bonding as well as various states of mental illness.

Harlow and his colleagues would later develop "evil artificial mothers" meant to "impart fear and insecurity to infant monkeys"—including one designed with brass spikes—but contrary to the researcher's hypothesis, these animals too demonstrated an attachment to their surrogates.

[38] Subsequent experiments would study the effects of total and partial isolation on the animals' mental health and interpersonal bonding using a stainless steel vertical chamber designed by Harlow, named the "pit of despair", which was found to produce "profound and prolonged depression" in monkeys.

Similarly, Harlow found that extended isolation in bare wire cages left monkeys with "profound behavioral abnormalities" including "self-clutching and rocking" and later "apathy and indifference to external stimulation".

[36][37] Writing on the researcher's legacy, John Gluck, a former student of Harlow's opined, "On the one hand, his work on monkey cognition and social development fostered a view of the animals as having rich subjective lives filled with intention and emotion.

Stephen Suomi, an early collaborator of Harlow, has continued to conduct maternal deprivation experiments on rhesus monkeys in his NIH laboratory and has been vigorously criticized by PETA, Members of Congress and others.

Some profoundly disagreed with the necessity for maternal (or equivalent) love in order to function normally,[42] or that the formation of an ongoing relationship with a child was an important part of parenting.

[43] In 1962, the WHO published Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of its Effects to which Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby's close colleague, contributed with his approval, to present the recent research and developments and to address misapprehensions.

The importance of these refinements of the maternal deprivation hypothesis was to reposition it as a "vulnerability factor" rather than a causative agent, with a number of varied influences determining which path a child would take.

The studies on which he based his conclusions involved almost complete lack of maternal care and it was unwarranted to generalise from this view that any separation in the first three years of life would be damaging.

For his subsequent development of attachment theory, Bowlby drew on concepts from ethology, cybernetics, information processing, developmental psychology and psychoanalysis.

[6] According to Zeanah, "ethological attachment theory, as outlined by John Bowlby ... 1969 to 1980 ... has provided one of the most important frameworks for understanding crucial risk and protective factors in social and emotional development in the first 3 years of life.