Mathematical object

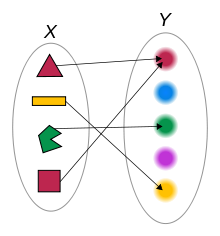

[1] Typically, a mathematical object can be a value that can be assigned to a symbol, and therefore can be involved in formulas.

Commonly encountered mathematical objects include numbers, expressions, shapes, functions, and sets.

In mathematics, objects are often seen as entities that exist independently of the physical world, raising questions about their ontological status.

[6] Quine-Putnam indispensability is an argument for the existence of mathematical objects based on their unreasonable effectiveness in the natural sciences.

From physics' use of Hilbert spaces in quantum mechanics and differential geometry in general relativity to biology's use of chaos theory and combinatorics (see mathematical biology), not only does mathematics help with predictions, it allows these areas to have an elegant language to express these ideas.

The argument is described by the following syllogism:[7](Premise 1) We ought to have ontological commitment to all and only the entities that are indispensable to our best scientific theories.

Instead, it suggests that they are merely convenient fictions or shorthand for describing relationships and structures within our language and theories.

This meant that not all mathematical truths could be derived purely from a logical system, undermining the logicist program.

One common understanding of formalism takes mathematics as not a body of propositions representing an abstract piece of reality but much more akin to a game, bringing with it no more ontological commitment of objects or properties than playing ludo or chess.

In this view, mathematics is about the consistency of formal systems rather than the discovery of pre-existing objects.