History of logic

Logic revived in the mid-nineteenth century, at the beginning of a revolutionary period when the subject developed into a rigorous and formal discipline which took as its exemplar the exact method of proof used in mathematics, a hearkening back to the Greek tradition.

The Nasadiya Sukta of the Rigveda (RV 10.129) contains ontological speculation in terms of various logical divisions that were later recast formally as the four circles of catuskoti: "A", "not A", "A and 'not A'", and "not A and not not A".

[4][14] Nagarjuna (c. 150–250 AD), the founder of the Madhyamaka ("Middle Way") developed an analysis known as the catuṣkoṭi (Sanskrit), a "four-cornered" system of argumentation that involves the systematic examination and rejection of each of the four possibilities of a proposition, P: However, Dignāga (c 480–540 AD) is sometimes said to have developed a formal syllogism,[15] and it was through him and his successor, Dharmakirti, that Buddhist logic reached its height; it is contested whether their analysis actually constitutes a formal syllogistic system.

[18] In China, a contemporary of Confucius, Mozi, "Master Mo", is credited with founding the Mohist school, whose canons dealt with issues relating to valid inference and the conditions of correct conclusions.

Due to the harsh rule of Legalism in the subsequent Qin dynasty, this line of investigation disappeared in China until the introduction of Indian philosophy by Buddhists.

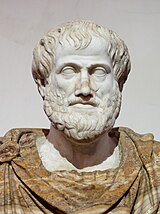

Fragments of early proofs are preserved in the works of Plato and Aristotle,[23] and the idea of a deductive system was probably known in the Pythagorean school and the Platonic Academy.

You must debar your thought from this way of search, nor let ordinary experience in its variety force you along this way, (namely, that of allowing) the eye, sightless as it is, and the ear, full of sound, and the tongue, to rule; but (you must) judge by means of the Reason (Logos) the much-contested proof which is expounded by me.Zeno of Elea, a pupil of Parmenides, had the idea of a standard argument pattern found in the method of proof known as reductio ad absurdum.

In the Categories, he attempts to discern all the possible things to which a term can refer; this idea underpins his philosophical work Metaphysics, which itself had a profound influence on Western thought.

[48] Stoic logic traces its roots back to the late 5th century BC philosopher Euclid of Megara, a pupil of Socrates and slightly older contemporary of Plato, probably following in the tradition of Parmenides and Zeno.

[49][50] Unlike with Aristotle, we have no complete works by the Megarians or the early Stoics, and have to rely mostly on accounts (sometimes hostile) by later sources, including prominently Diogenes Laërtius, Sextus Empiricus, Galen, Aulus Gellius, Alexander of Aphrodisias, and Cicero.

[52] The works of Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Al-Ghazali, Averroes and other Muslim logicians were based on Aristotelian logic and were important in communicating the ideas of the ancient world to the medieval West.

In this work, Bacon rejects the syllogistic method of Aristotle in favor of an alternative procedure "which by slow and faithful toil gathers information from things and brings it into understanding".

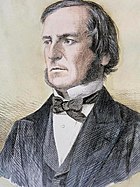

[2] The revival of logic occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, at the beginning of a revolutionary period where the subject developed into a rigorous and formalistic discipline whose exemplar was the exact method of proof used in mathematics.

The development of modern logic falls into roughly five periods:[106] The idea that inference could be represented by a purely mechanical process is found as early as Raymond Llull, who proposed a (somewhat eccentric) method of drawing conclusions by a system of concentric rings.

Three hundred years after Llull, the English philosopher and logician Thomas Hobbes suggested that all logic and reasoning could be reduced to the mathematical operations of addition and subtraction.

Leibniz says that ordinary languages are subject to "countless ambiguities" and are unsuited for a calculus, whose task is to expose mistakes in inference arising from the forms and structures of words;[110] hence, he proposed to identify an alphabet of human thought comprising fundamental concepts which could be composed to express complex ideas,[111] and create a calculus ratiocinator that would make all arguments "as tangible as those of the Mathematicians, so that we can find our error at a glance, and when there are disputes among persons, we can simply say: Let us calculate.

[113] Bolzano anticipated a fundamental idea of modern proof theory when he defined logical consequence or "deducibility" in terms of variables:[114]Hence I say that propositions

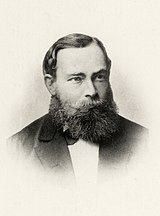

[121] In his Symbolic Logic (1881), John Venn used diagrams of overlapping areas to express Boolean relations between classes or truth-conditions of propositions.

Boole's goals were "to go under, over, and beyond" Aristotle's logic by 1) providing it with mathematical foundations involving equations, 2) extending the class of problems it could treat—from assessing validity to solving equations—and 3) expanding the range of applications it could handle—e.g.

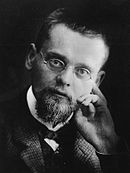

"[130] Frege's first work, the Begriffsschrift ("concept script") is a rigorously axiomatised system of propositional logic, relying on just two connectives (negational and conditional), two rules of inference (modus ponens and substitution), and six axioms.

[132] At the outset Frege abandons the traditional "concepts subject and predicate", replacing them with argument and function respectively, which he believes "will stand the test of time.

[136] This period overlaps with the work of what is known as the "mathematical school", which included Dedekind, Pasch, Peano, Hilbert, Zermelo, Huntington, Veblen and Heyting.

The first is that no consistent system of axioms whose theorems can be listed by an effective procedure such as an algorithm or computer program is capable of proving all facts about the natural numbers.

Later in the decade, Gödel developed the concept of set-theoretic constructibility, as part of his proof that the axiom of choice and the continuum hypothesis are consistent with Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory.

Since Gentzen's work, natural deduction and sequent calculi have been widely applied in the fields of proof theory, mathematical logic and computer science.

[143] Alonzo Church and Alan Turing proposed formal models of computability, giving independent negative solutions to Hilbert's Entscheidungsproblem in 1936 and 1937, respectively.

Later work by Emil Post and Stephen Cole Kleene in the 1940s extended the scope of computability theory and introduced the concept of degrees of unsolvability.

[146] The priority method, discovered independently by Albert Muchnik and Richard Friedberg in the 1950s, led to major advances in the understanding of the degrees of unsolvability and related structures.

In the 1960s, Abraham Robinson used model-theoretic techniques to develop calculus and analysis based on infinitesimals, a problem that first had been proposed by Leibniz.

Although some basic novelties syncretizing mathematical and philosophical logic were shown by Bolzano in the early 1800s, it was Ernst Mally, a pupil of Alexius Meinong, who was to propose the first formal deontic system in his Grundgesetze des Sollens, based on the syntax of Whitehead's and Russell's propositional calculus.