Matter

[3] Usually atoms can be imagined as a nucleus of protons and neutrons, and a surrounding "cloud" of orbiting electrons which "take up space".

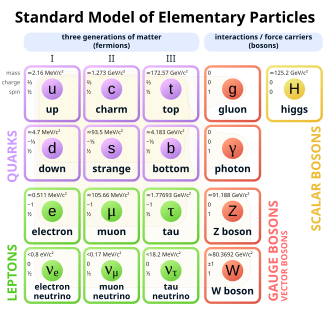

In the Standard Model of particle physics, matter is not a fundamental concept because the elementary constituents of atoms are quantum entities which do not have an inherent "size" or "volume" in any everyday sense of the word.

Some of these ways are based on loose historical meanings from a time when there was no reason to distinguish mass from simply a quantity of matter.

Sometimes in the field of physics "matter" is simply equated with particles that exhibit rest mass (i.e., that cannot travel at the speed of light), such as quarks and leptons.

At a microscopic level, the constituent "particles" of matter such as protons, neutrons, and electrons obey the laws of quantum mechanics and exhibit wave–particle duality.

At an even deeper level, protons and neutrons are made up of quarks and the force fields (gluons) that bind them together, leading to the next definition.

Carithers and Grannis state: "Ordinary matter is composed entirely of first-generation particles, namely the [up] and [down] quarks, plus the electron and its neutrino.

[25] In other words, most of what composes the "mass" of ordinary matter is due to the binding energy of quarks within protons and neutrons.

However, an explanation for why matter occupies space is recent, and is argued to be a result of the phenomenon described in the Pauli exclusion principle,[33][34] which applies to fermions.

Although we do not encounter them in everyday life, antiquarks (such as the antiproton) and antileptons (such as the positron) are the antiparticles of the quark and the lepton, are elementary fermions as well, and have essentially the same properties as quarks and leptons, including the applicability of the Pauli exclusion principle which can be said to prevent two particles from being in the same place at the same time (in the same state), i.e. makes each particle "take up space".

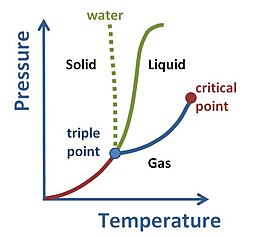

In bulk, matter can exist in several different forms, or states of aggregation, known as phases,[49] depending on ambient pressure, temperature and volume.

[50] A phase is a form of matter that has a relatively uniform chemical composition and physical properties (such as density, specific heat, refractive index, and so forth).

These phases include the three familiar ones (solids, liquids, and gases), as well as more exotic states of matter (such as plasmas, superfluids, supersolids, Bose–Einstein condensates, ...).

Antimatter is not found naturally on Earth, except very briefly and in vanishingly small quantities (as the result of radioactive decay, lightning or cosmic rays).

Antiparticles and some stable antimatter (such as antihydrogen) can be made in tiny amounts, but not in enough quantity to do more than test a few of its theoretical properties.

In October 2017, scientists reported further evidence that matter and antimatter, equally produced at the Big Bang, are identical, should completely annihilate each other and, as a result, the universe should not exist.

Further, outside of natural or artificial nuclear reactions, there is almost no antimatter generally available in the universe (see baryon asymmetry and leptogenesis), so particle annihilation is rare in normal circumstances.

[63][64] Observational evidence of the early universe and the Big Bang theory require that this matter have energy and mass, but not be composed of ordinary baryons (protons and neutrons).

Its precise nature is currently a mystery, although its effects can reasonably be modeled by assigning matter-like properties such as energy density and pressure to the vacuum itself.

[6] Jain philosophers included the soul (jiva), adding qualities such as taste, smell, touch, and color to each atom.

[68] They extended the ideas found in early literature of the Hindus and Buddhists by adding that atoms are either humid or dry, and this quality cements matter.

[77] Like Descartes, Hobbes, Boyle, and Locke argued that the inherent properties of bodies were limited to extension, and that so-called secondary qualities, like color, were only products of human perception.

In the third of his "Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy", Newton lists the universal qualities of matter as "extension, hardness, impenetrability, mobility, and inertia".

[80] The "primary" properties of matter were amenable to mathematical description, unlike "secondary" qualities such as color or taste.

Newton's use of gravitational force, which worked "at a distance", effectively repudiated Descartes's mechanics, in which interactions happened exclusively by contact.

[82] He argued matter has other inherent powers besides the so-called primary qualities of Descartes, et al.[83] Since Priestley's time, there has been a massive expansion in knowledge of the constituents of the material world (viz., molecules, atoms, subatomic particles).

[85] He carefully separates "matter" from space and time, and defines it in terms of the object referred to in Newton's first law of motion.

In the 19th century, the term "matter" was actively discussed by a host of scientists and philosophers, and a brief outline can be found in Levere.

[96][97] The modern conception of matter has been refined many times in history, in light of the improvement in knowledge of just what the basic building blocks are, and in how they interact.

Different building blocks apply depending upon whether one defines matter on an atomic or elementary particle level.