Quark

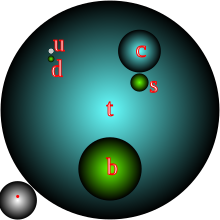

Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nuclei.

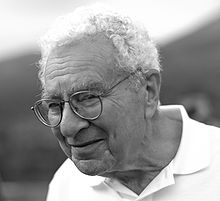

[5] Quarks were introduced as parts of an ordering scheme for hadrons, and there was little evidence for their physical existence until deep inelastic scattering experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in 1968.

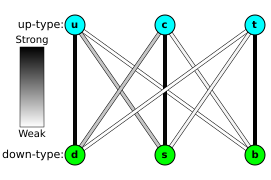

[9] Unlike leptons, quarks possess color charge, which causes them to engage in the strong interaction.

The resulting attraction between different quarks causes the formation of composite particles known as hadrons (see § Strong interaction and color charge below).

[5] The proposal came shortly after Gell-Mann's 1961 formulation of a particle classification system known as the Eightfold Way – or, in more technical terms, SU(3) flavor symmetry, streamlining its structure.

Their model involved three flavors of quarks, up, down, and strange, to which they ascribed properties such as spin and electric charge.

There was particular contention about whether the quark was a physical entity or a mere abstraction used to explain concepts that were not fully understood at the time.

Sheldon Glashow and James Bjorken predicted the existence of a fourth flavor of quark, which they called charm.

The addition was proposed because it allowed for a better description of the weak interaction (the mechanism that allows quarks to decay), equalized the number of known quarks with the number of known leptons, and implied a mass formula that correctly reproduced the masses of the known mesons.

[31] Deep inelastic scattering experiments conducted in 1968 at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) and published on October 20, 1969, showed that the proton contained much smaller, point-like objects and was therefore not an elementary particle.

[6][7][32] Physicists were reluctant to firmly identify these objects with quarks at the time, instead calling them "partons" – a term coined by Richard Feynman.

Richard Taylor, Henry Kendall and Jerome Friedman received the 1990 Nobel Prize in physics for their work at SLAC.

The strange quark's existence was indirectly validated by SLAC's scattering experiments: not only was it a necessary component of Gell-Mann and Zweig's three-quark model, but it provided an explanation for the kaon (K) and pion (π) hadrons discovered in cosmic rays in 1947.

[37] In a 1970 paper, Glashow, John Iliopoulos and Luciano Maiani presented the GIM mechanism (named from their initials) to explain the experimental non-observation of flavor-changing neutral currents.

Since "quark" (meaning, for one thing, the cry of the gull) was clearly intended to rhyme with "Mark", as well as "bark" and other such words, I had to find an excuse to pronounce it as "kwork".

[66] While "truth" never did catch on, accelerator complexes devoted to massive production of bottom quarks are sometimes called "beauty factories".

It is sometimes visualized as the rotation of an object around its own axis (hence the name "spin"), though this notion is somewhat misguided at subatomic scales because elementary particles are believed to be point-like.

[69] Spin can be represented by a vector whose length is measured in units of the reduced Planck constant ħ (pronounced "h bar").

[76] The system of attraction and repulsion between quarks charged with different combinations of the three colors is called strong interaction, which is mediated by force carrying particles known as gluons; this is discussed at length below.

A quark, which will have a single color value, can form a bound system with an antiquark carrying the corresponding anticolor.

[78] Just as the laws of physics are independent of which directions in space are designated x, y, and z, and remain unchanged if the coordinate axes are rotated to a new orientation, the physics of quantum chromodynamics is independent of which directions in three-dimensional color space are identified as blue, red, and green.

Every quark flavor f, each with subtypes fB, fG, fR corresponding to the quark colors,[79] forms a triplet: a three-component quantum field that transforms under the fundamental representation of SU(3)c.[80] The requirement that SU(3)c should be local – that is, that its transformations be allowed to vary with space and time – determines the properties of the strong interaction.

Mass and total angular momentum (J; equal to spin for point particles) do not change sign for the antiquarks.

As described by quantum chromodynamics, the strong interaction between quarks is mediated by gluons, massless vector gauge bosons.

In the standard framework of particle interactions (part of a more general formulation known as perturbation theory), gluons are constantly exchanged between quarks through a virtual emission and absorption process.

[96] Under sufficiently extreme conditions, quarks may become "deconfined" out of bound states and propagate as thermalized "free" excitations in the larger medium.

Eventually, color confinement would be effectively lost in an extremely hot plasma of freely moving quarks and gluons.

[99] The exact conditions needed to give rise to this state are unknown and have been the subject of a great deal of speculation and experimentation.

It is believed that in the period prior to 10−6 seconds after the Big Bang (the quark epoch), the universe was filled with quark–gluon plasma, as the temperature was too high for hadrons to be stable.

This liquid would be characterized by a condensation of colored quark Cooper pairs, thereby breaking the local SU(3)c symmetry.

Σ ++

c baryon , at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1974

![A tree diagram consisting mostly of straight arrows. A down quark forks into an up quark and a wavy-arrow W[superscript minus] boson, the latter forking into an electron and reversed-arrow electron antineutrino.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Beta_Negative_Decay.svg/192px-Beta_Negative_Decay.svg.png)