Maurice Benyovszky

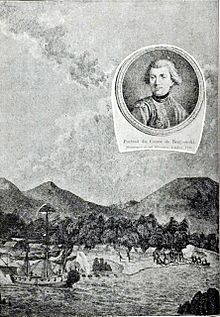

Count Maurice Benyovszky de Benyó et Urbanó (Hungarian: Benyovszky Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin Ágost; Polish: Maurycy Beniowski; Slovak: Móric Beňovský; 20 September 1746 – 24 May 1786)[1] was a military officer, adventurer, and writer from the Kingdom of Hungary, who described himself as both a Hungarian and a Pole.

After a failed venture in Fiume (present-day Rijeka), he travelled to America and obtained financial backing for a second voyage to Madagascar.

[3][4][5][6][7][8] Not the least is Benyovszky's opening statement that he was born in 1741, rather than 1746 – a birth-date which allowed him to claim having fought in the Seven Years' War with the rank of lieutenant and having studied navigation.

[10] He was baptised under the Latin names Mattheus Mauritius Michal Franciscus Seraphinus (Hungarian: Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin).

[11] Maurice was the son of Sámuel Benyovszky, who came from Turóc County in the Kingdom of Hungary (today partially Turiec region, in present-day Slovakia) and is said to have served as a colonel in the Hussars of the Austrian Army.

This action led his mother's family to file a criminal complaint against him, and he was called to stand trial in Nyitra (present-day Nitra).

Before the conclusion of the trial, Benyovszky fled to Poland to join his uncle, Jan Tibor Benyowski de Benyo, a Polish nobleman.

[20] In July 1768, Benyovszky travelled to Poland[21] to join the patriotic forces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who had organised resistance in the Confederation of Bar (Konfederacja Barska), a movement in rebellion against Polish king Stanisław August Poniatowski, lately installed by Russia.

In April 1769, he was captured by the Russian forces near Ternopil in Ukraine, imprisoned in the town of Polonne, before being transferred to Kiev in July, and finally to Kazan in September.

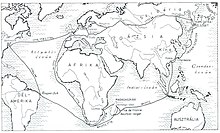

[23] In the company of several other exiles and prisoners – most notably the Swede August Winbladh, and the Russian army-officers Vasilii Panov, Asaf Baturin and Ippolit Stepanov,[24] all of whom played a major role in Benyovszky's life in the next two years – he reached Bolsheretsk, at that time the administrative capital of Kamchatka, in September 1770.

From the list of those[26] who participated in the escape (70 men, women, and children), it is evident that the majority were not prisoners or exiles of any sort, but just ordinary working people of Kamchatka.

Such a route is completely absent from three other separate accounts of the voyage (by Ippolit Stepanov,[30] Ivan Ryumin,[31] and Gerasim Izmailov[32]).

During this time, the sailor Izmailov who was judged to be organising a mutiny and two other Kamchatkans were left on the island when the ship finally sailed southwards.

[34] Izmailov subsequently carved out a career as an explorer and trader in the Aleutians and the Alaskan coast, providing information to Captain James Cook in the summer of 1778.

Ian Inkster's "Orientat Enlightenment: The Problematic Military Claims of Count Maurice Auguste Conte de Benyowsky in Formosa during 1771" criticizes the Taiwan section specifically.

[39] Even in Father de Mailla's account of Taiwan in 1715, in which he portrayed the Chinese in a very negative manner, and spoke of the entire east being in rebellion against the west, the aborigines were still unable to put up a fighting force of more than 30 or 40 armed with arrows and javelins.

Horses were introduced to Taiwan starting in the Dutch period but it is highly unlikely that aborigines of the northeast coast had acquired so many that they could train them for large scale warfare.

[44] Benyovszky took responsibility for selling the ship and all the furs they had loaded at Kamchatka, and then negotiated with the various European trading establishments for passage back to Europe.

Over the next months, he toured the ministries and salons of Paris, hoping to persuade someone to fund a trading expedition to one of the several places he claimed to have visited.

[52] It does not appear to have gone well, since the explorer Kerguelen arrived there shortly afterwards to discover that the Malagasy claimed Benyovszky was at war with them: supplies were therefore hard to come by.

[56] Despite these setbacks, over the following two years, Benyovszky sent back to Paris positive reports of his advances in Madagascar, along with requests for more funding, supplies, and personnel.

[57][58] The French authorities and traders on Mauritius, meanwhile, were also writing to Paris, complaining of the problems which Benyovszky was causing for their own trade with Madagascar.

Following the arrival of the inspectors' report in Paris, the few surviving 'Benyovszky Volunteers' were disbanded in May 1778 and the trading post was eventually dismantled by order of the French government in June 1779.

He then made his way to the United States and, with a recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in Paris, attempted to persuade George Washington to fund a militia under Benyovszky's leadership, to fight in the American War of Independence.

In October of that year, the ship Intrepid sailed for Madagascar, arriving near Cap St Sebastien in north-west of the island, June 1785.

Anxious about another disruption to trade, François de Souillac, the French governor of Mauritius waited for fair winds and then sent a small military force over to Madagascar to deal with Benyovszky.

Much of what Benyovszky claimed to have done in Poland, Kamchatka, Japan, Formosa, and Madagascar is questionable at best, but in any case has left no lasting traces in the history of war, exploration, or colonialism.

[79] His legacy resides largely in his autobiography (Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky), which was published in two volumes in 1790 by friends of Magellan, who was by then, as a result of the failed Malagasy venture, in serious financial difficulties.

[80][3][81][5] Despite this criticism, it was a great publishing success, and has since been translated into several languages; (German 1790, 1791, 1796, 1797; Dutch 1791; French 1791; Swedish 1791; Polish 1797; Slovak 1808; and Hungarian 1888).

[88] The Polish writer Arkady Fiedler visited Madagascar in 1937, spent several months in the town of Ambinanitelo and later wrote a popular travel book describing his experiences.