Age of Discovery

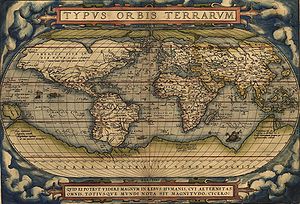

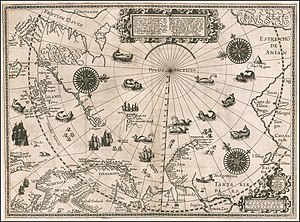

The extensive overseas exploration, particularly the opening of maritime routes to the Indies and the European colonization of the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese, later joined by the English, French and Dutch, spurred in the international global trade.

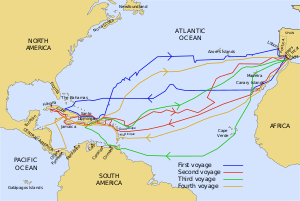

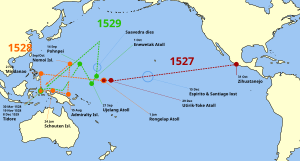

[4][5] During the Age of Discovery, Spain sponsored and financed the transatlantic voyages of the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus, which from 1492 to 1504 marked the start of colonization in the Americas, and the expedition of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan to open a route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, which later achieved the first circumnavigation of the globe between 1519 and 1522.

The decline of the Fatimid Caliphate's naval strength, which started before the First Crusade, helped the maritime Italian states, mainly Venice, Genoa and Pisa, dominate trade in the Eastern Mediterranean, with merchants there becoming wealthy and politically influential.

In the 12th century, the regions of Flanders, Hainault, and Brabant produced the finest quality textiles in northwest Europe, which encouraged merchants from Genoa and Venice to sail there from the Mediterranean, through the Strait of Gibraltar, and up the Atlantic coast.

Prior to the late 13th/early 14th centuries, northern European ships were typically clinker built,[b] with a single mast setting a square sail and a centre-line rudder hung on the sternpost with pintles and gudgeons.

[51] In that year, the Genoese attempted their first Atlantic exploration when merchant brothers Vadino and Ugolino Vivaldi sailed from Genoa with two galleys, but disappeared off the Moroccan coast, feeding fears of oceanic travel.

In 1487, Portuguese envoys Pero da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva were sent on a covert mission to gather intelligence on a potential sea route to India and inquire about Prester John, a Nestorian patriarch and king, believed to rule over parts of the subcontinent.

Muslim traders dominated maritime routes throughout the Indian Ocean, tapping source regions in the Far East and shipping for trading emporiums in India, mainly Kozhikode, westward to Ormus in the Persian Gulf and Jeddah in the Red Sea.

Venetian merchants distributed the goods through Europe until the rise of the Ottoman Empire, which eventually led to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, barring Europeans from some important combined-land-sea routes in areas around the Aegean, Bosporus, and Black Sea.

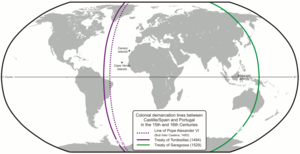

In 1455, Pope Nicholas V issued the bull Romanus Pontifex reinforcing the previous Dum Diversas (1452), granting all lands and seas discovered beyond Cape Bojador to King Afonso V of Portugal and his successors, as well as mostly cutting off trade to and permitting conquest and increased war against Muslims and pagans, initiating a mare clausum policy in the Atlantic.

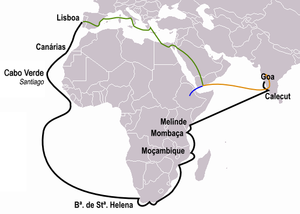

The next crucial breakthrough was in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of Africa, which he named Cabo das Tormentas, "Cape of Storms", anchoring at Mossel Bay and then sailing east as far as the mouth of the Great Fish River, proving the Indian Ocean was accessible from the Atlantic.

Based on many later stories of the phantom island known as Bacalao and the carvings on Dighton Rock some have speculated that Portuguese explorer João Vaz Corte-Real discovered Newfoundland in 1473, but the sources are considered unreliable.

The Crown of Aragon had been an important maritime power in the Mediterranean, controlling territories in eastern Spain, southwestern France, major islands like Sicily, Malta, and the Kingdom of Naples and Sardinia, with mainland possessions as far as Greece.

Portugal gained control over Africa, Asia, and eastern South America (Brazil), encompassing everything outside Europe east of a line drawn 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese).

[citation needed] Later the Spanish territory would prove to include huge areas of the continental mainland of North and South America, though Portuguese-controlled Brazil would expand across the line, and settlements by other European powers ignored the treaty.

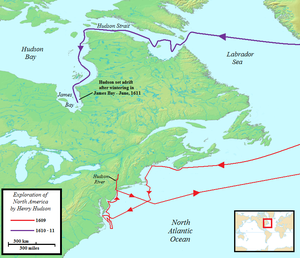

Sailing from Bristol, probably backed by the local Society of Merchant Venturers, Cabot crossed the Atlantic from a northerly latitude hoping the voyage to the "West Indies" would be shorter[111] and made landfall somewhere in North America, possibly Newfoundland.

During the voyage he discovered the mouth of the Orinoco River on the north coast of South America (now Venezuela) and thought that the huge quantity of fresh water coming from it could only be from a continental land mass, which he was certain was the Asian mainland.

In April 1500, the second Portuguese India Armada, headed by Pedro Álvares Cabral, with a crew of expert captains, encountered the Brazilian coast as it swung westward in the Atlantic while performing a large "volta do mar" to avoid becalming in the Gulf of Guinea.

[129] Christopher de Haro, a Flemish of Sephardic origin (one of the financiers of the expedition along with D. Nuno Manuel), who would serve the Spanish Crown after 1516, believed the navigators had discovered a southern strait to west and Asia.

King John II of Portugal's experts rejected it, for they held the opinion that Columbus's estimation of a travel distance of 2,400 miles (3,860 km) was low,[131] and in part because Bartolomeu Dias departed in 1487 trying the rounding of the southern tip of Africa.

In 1513, about 40 miles (64 kilometres) south of Acandí, in present-day Colombia, Spanish Vasco Núñez de Balboa heard unexpected news of an "other sea" rich in gold, which he received with great interest.

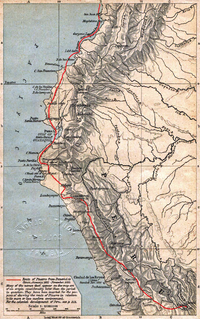

In 1533, Pizarro invaded Cuzco with indigenous troops and wrote to King Charles I: "This city is the greatest and the finest ever seen in this country or anywhere in the Indies ... it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would be remarkable even in Spain."

Between 1520 and 1521, the Portuguese João Álvares Fagundes, accompanied by couples of mainland Portugal and the Azores, explored Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (possibly reaching the Bay of Fundy on the Minas Basin[170]), and established a fishing colony on the Cape Breton Island that would last until at least the 1570s or near the end of the century.

Dutch navigator and colonial governor, Willem Janszoon sailed from the Netherlands for the East Indies for the third time on December 18, 1603, as captain of the Duyfken (or Duijfken, meaning "Little Dove"), one of twelve ships of the great fleet of Steven van der Hagen.

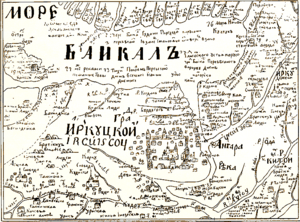

[197] In 1639, a group of explorers led by Ivan Moskvitin became the first Russians to reach the Pacific Ocean and to discover the Sea of Okhotsk, having built a winter camp on its shore at the Ulya River mouth.

He built winter quarters at Albazin, then sailed down Amur and found Achansk, which preceded the present-day Khabarovsk, defeating or evading large armies of Daurian Manchu Chinese and Koreans on his way.

[218] The arrival of the Portuguese to Japan in 1543 initiated the Nanban trade period, with the Japanese adopting technologies and cultural practices, like the arquebus, European-style cuirasses, European ships, Christianity, decorative art, and language.

[224] The Portuguese friar Gaspar da Cruz (c. 1520–70) wrote the first complete book on China published in Europe; it included information on its geography, provinces, royalty, official class, bureaucracy, shipping, architecture, farming, craftsmanship, merchant affairs, clothing, religious and social customs, music and instruments, writing, education, and justice.

[227][228] Kraak, mainly the blue and white porcelain, was imitated all over the world by potters in Arita, Japan and Persia—where Dutch merchants turned when the fall of the Ming dynasty rendered Chinese originals unavailable[229]—and ultimately in Delftware.

Antonio de Morga (1559–1636), a Spanish official in Manila, listed an extensive inventory of goods that were traded by Ming China at the turn of the 16th to 17th century, noting there were "rarities which, did I refer to them all, I would never finish, nor have sufficient paper for it".