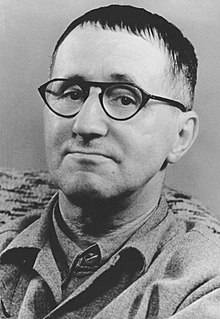

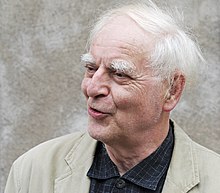

Max Frisch

Frisch made his first contribution to the newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) in May 1931, but the death of his father in March 1932 persuaded him to make a full-time career of journalism in order to generate an income to support his mother.

Frisch seems to have found many of them excessively introspective even at the time, and tried to distract himself by taking labouring jobs involving physical exertion, including a period in 1932 when he worked on road construction.

Frisch failed to anticipate how Germany's National Socialism would evolve, and his early apolitical novels were published by the Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt (DVA) without encountering any difficulties from the German censors.

Although Swiss neutrality meant that army membership was not a full-time occupation, the country mobilised to be ready to resist a German invasion, and by 1945 Frisch had clocked up 650 days of active service.

After receiving his diploma in the summer of 1940, Frisch accepted an offer of a permanent position in Dunkel's architecture studio, and for the first time in his life was able to afford a home of his own.

The NZZ, then as now his native city's powerfully influential newspaper, pilloried the piece on its front page, claiming that it "embroidered" the horrors of National Socialism, and they refused to print Frisch's rebuttal.

Nevertheless, when he returned home the resolutely conservative NZZ concluded that by visiting Poland Frisch had simply confirmed his status as a Communist sympathizer, and not for the first time refused to print his rebuttal of their simplistic conclusions.

The story concerns a state prosecutor named Martin who grows bored with his middle-class existence, and drawing inspiration from the legend of Count Oederland, sets out in search of total freedom, using an axe to kill anyone who stands in his way.

It nevertheless attracted controversy, especially after it opened in the United States, from those who thought that it treated with unnecessary frivolity issues which were still extremely painful so soon after the Nazi Holocaust had been publicised in the west.

Frisch himself wrote of Gantenbein that his purpose was "to show the reality of an individual by having him appear as a blank patch outlined by the sum of fictional entities congruent with his personality.

In October 1975, slightly improbably, the Swiss dramatist Frisch accompanied Chancellor Schmidt on what for them both was their first visit to China,[19] as part of an official West German delegation.

Rolf Keiser points out that the diary format enables Frisch most forcefully to demonstrate his familiar theme that thoughts are always based on one specific standpoint and its context; and that it can never be possible to present a comprehensive view of the world, nor even to define a single life, using language alone.

In an interview with Heinz Ludwig Arnold Frisch vigorously rejected their allegorical approach: "I have established only that when I apply the parable format, I am obliged to deliver a message that I actually do not have".

In Biography: A game (Biografie: Ein Spiel) a life-story is retrospectively "corrected", while Santa Cruz and Count Oederland (Graf Öderland) combine aspects of a dream sequence with the features of a morality tale.

The critic Hellmuth Karasek identified in Frisch's plays a mistrust of dramatic structure, apparent from the way in which Don Juan or the Love of Geometry applies theatrical method.

His early work is strongly influenced by the poetical imagery of Albin Zollinger, and not without a certain imitative lyricism, something from which in later life he would distance himself, dismissing it as "phoney poeticising" ("falsche Poetisierung").

[49] Claus Reschke says that the male protagonists in Frisch's work are all similar modern Intellectual types: egocentric, indecisive, uncertain in respect of their own self-image, they often misjudge their actual situation.

Frisch's compositions tend to be centred on male protagonists, around which his leading female characters, virtually interchangeable, fulfil a structural and focused function.

[51] From her thoughtfully feminist perspective, Karin Struck saw Frisch's male protagonists manifesting a high level of dependency on the female characters, but the women remain strangers to them.

[53] Death is an ongoing theme in Frisch's work, but during his early and heyday periods it remains in the background, overshadowed by identity issues and relationships problems.

"According to Swiss writer and literary critic Hugo Loetscher, the questionnaires are the intellectual and formal highlight of this diary: “Brilliant, precise and informative, our own person and therefore ourselves are circled using question marks".

[55] In eleven questionnaires Frisch asks seemingly innocuous questions on the topics of altruism, marriage, property, women, friendship, money, home, hope, humor, children and death.

"[59] Sonja Rüegg, writing in 1998, says that Frisch's aesthetics is driven by a fundamentally anti-ideological and critical animus, formed from a recognition of the writer's status as an outsider within society.

In particular in Überfremdung 1 Frisch expresses all his annoyance at the narrow-mindedness of a good part of the people and institutions of Switzerland in the face of the growing phenomenon of immigration in the fifties and sixties: "A small master nation sees itself in danger: workers have been called and human beings are coming.

As a young writer he also had work accepted by an established publishing house, the Munich based Deutschen Verlags-Anstalt, which already included a number of distinguished German-language authors on its lists.

[68] The experience encouraged him to pay more attention to audiences outside his native Switzerland, notably in the new and rapidly developing Federal Republic of Germany, where the novel I'm Not Stiller succeeded commercially on a scale that till then had eluded Frisch, enabling him now to become a full-time professional writer.

[71] The Fire Raisers and Andorra are the most successful German language plays of all time, with respectively 250 and 230 productions up till 1996, according to an estimate made by the literary critic Volker Hage.

More than a generation after that, in 1998, when it was the turn of Swiss literature to be the special focus[76] at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the literary commentator Andreas Isenschmid identified some leading Swiss writers from his own (baby-boomer) generation such as Ruth Schweikert, Daniel de Roulet and Silvio Huonder in whose works he had found "a curiously familiar old tone, resonating from all directions, and often almost page by page, uncanny echoes from Max Frisch's Stiller.

[80] Despite some ideologically driven official criticism of his "individualism", "negativity" and "modernism", Frisch's works were actively translated into Russian, and were featured in some 150 reviews in the Soviet Union.

[84] Adolf Muschg, purporting to address Frisch directly on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, contemplates the older man's contribution: "Your position in the history of literature, how can it be described?