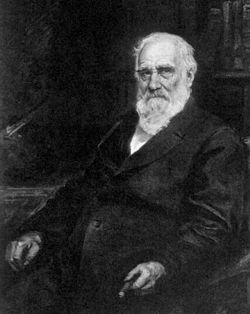

Max Joseph von Pettenkofer

He is known for his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper sewage disposal.

In particular he argued in favor of a variety of conditions collectively contributing to the incidence of disease including: personal state of health, the fermentation of environmental ground water, and also the germ in question.

He was a nephew of Franz Xaver (1783–1850), who from 1823 was a surgeon and apothecary to the Bavarian court and was the author of some chemical investigations on the vegetable alkaloids.

In his earlier years he devoted himself to chemistry, both theoretical and applied, publishing papers on a wide range of topics.

This work derived from his position at the Munich mint and was centered around minimizing the costs of currency conversion by separating the precious metals from one another.

[4] He continued his publications in a wide variety of other fields as well including: the formation of aventurine glass, the manufacture of illuminating gas from wood, the preservation of oil paintings, and an improved process for cement production among other things.

[5] Pettenkofer's name is most familiar in connection with his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper sewage disposal.

[6] As one of the principal proponents for the field of hygiene in Munich he was responsible for giving presentations to government officials in order to secure funding for public health projects.

He asserted that there was a strong link between proper circulation of "good air" through houses, adequate space for living, and the health of the occupants.

He firmly believed that the causes of disease were related to the multitude of environmental factors that the people of Munich were required to live in.

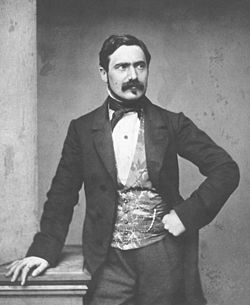

[6] During his career his position as a strong proponent of public health at times placed him at odds with his contemporaries, most notably Robert Koch.

During his career Koch identified and isolated a large number of bacterial strains and was a supporter of the theory that these germs were the main causes of disease.

In one specific case, Pettenkofer obtained bouillon laced with a large dose of Vibrio cholerae bacteria from Robert Koch, the proponent of the theory that the bacterium was the sole cause of the disease.

[8] In the same magazine, Pettenkofer is recognized to have developed an accurate quantitative analysis method for determining atmospheric carbon dioxide.

[9] The 1899 handwritten manuscript 'On the self purification of rivers' and Pettenkofer's papers can be found at the archives of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

[6] Max Joseph von Pettenkofer's name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.