Faraday's law of induction

This phenomenon, known as electromagnetic induction, is the fundamental operating principle of transformers, inductors, and many types of electric motors, generators and solenoids.

[2][3] The Maxwell–Faraday equation (listed as one of Maxwell's equations) describes the fact that a spatially varying (and also possibly time-varying, depending on how a magnetic field varies in time) electric field always accompanies a time-varying magnetic field, while Faraday's law states that emf (electromagnetic work done on a unit charge when it has traveled one round of a conductive loop) appears on a conductive loop when the magnetic flux through the surface enclosed by the loop varies in time.

[5][6] Faraday's notebook on August 29, 1831[8] describes an experimental demonstration of electromagnetic induction (see figure)[9] that wraps two wires around opposite sides of an iron ring (like a modern toroidal transformer).

His assessment of newly-discovered properties of electromagnets suggested that when current started to flow in one wire, a sort of wave would travel through the ring and cause some electrical effect on the opposite side.

[7] His notebook entry also noted that fewer wraps for the battery side resulted in a greater disturbance of the galvanometer's needle.

For example, he saw transient currents when he quickly slid a bar magnet in and out of a coil of wires, and he generated a steady (DC) current by rotating a copper disk near the bar magnet with a sliding electrical lead ("Faraday's disk").

[10]: 191–195 Michael Faraday explained electromagnetic induction using a concept he called lines of force.

[10]: 510 An exception was James Clerk Maxwell, who in 1861–62 used Faraday's ideas as the basis of his quantitative electromagnetic theory.

[10]: 510 [11][12] In Maxwell's papers, the time-varying aspect of electromagnetic induction is expressed as a differential equation which Oliver Heaviside referred to as Faraday's law even though it is different from the original version of Faraday's law, and does not describe motional emf.

According to Albert Einstein, much of the groundwork and discovery of his special relativity theory was presented by this law of induction by Faraday in 1834.

[18]: ch17 [19][20] (Although some sources state the definition differently, this expression was chosen for compatibility with the equations of special relativity.)

Equivalently, it is the voltage that would be measured by cutting the wire to create an open circuit, and attaching a voltmeter to the leads.

The laws of induction of electric currents in mathematical form were established by Franz Ernst Neumann in 1845.

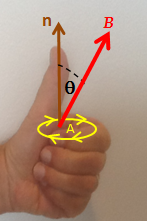

A left hand rule helps doing that, as follows:[22][23] For a tightly wound coil of wire, composed of N identical turns, each with the same ΦB, Faraday's law of induction states that[24][25]

A charge-generated E-field can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar field that is a solution to Poisson's equation, and has a zero path integral.

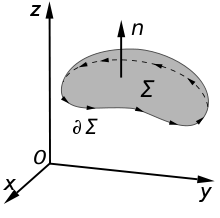

The surface integral at the right-hand side is the explicit expression for the magnetic flux ΦB through Σ.

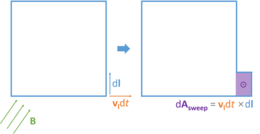

[28][29] The starting point is the time-derivative of flux through an arbitrary surface Σ (that can be moved or deformed) in space:

This total time derivative can be evaluated and simplified with the help of the Maxwell–Faraday equation and some vector identities; the details are in the box below:

It is tempting to generalize Faraday's law to state: If ∂Σ is any arbitrary closed loop in space whatsoever, then the total time derivative of magnetic flux through Σ equals the emf around ∂Σ.

[31] Alternatively, one can always correctly calculate the emf by combining Lorentz force law with the Maxwell–Faraday equation:[18]: ch17 [32] where "it is very important to notice that (1) [vm] is the velocity of the conductor ... not the velocity of the path element dl and (2) in general, the partial derivative with respect to time cannot be moved outside the integral since the area is a function of time.

James Clerk Maxwell drew attention to this fact in his 1861 paper On Physical Lines of Force.

Yet in our explanation of the rule we have used two completely distinct laws for the two cases – v × B for "circuit moves" and ∇ × E = −∂tB for "field changes".

We know of no other place in physics where such a simple and accurate general principle requires for its real understanding an analysis in terms of two different phenomena.

[dubious – discuss] In the general case, explanation of the motional emf appearance by action of the magnetic force on the charges in the moving wire or in the circuit changing its area is unsatisfactory.

As a matter of fact, the charges in the wire or in the circuit could be completely absent, will then the electromagnetic induction effect disappear in this case?

This situation is analyzed in the article, in which, when writing the integral equations of the electromagnetic field in a four-dimensional covariant form, in the Faraday’s law the total time derivative of the magnetic flux through the circuit appears instead of the partial time derivative.

From the physical point of view, it is better to speak not about the induction emf, but about the induced electric field strength

emerges in this part of the circuit in the comoving reference frame K’ as a result of the Lorentz transformation of the magnetic field

Reflection on this apparent dichotomy was one of the principal paths that led Albert Einstein to develop special relativity: It is known that Maxwell's electrodynamics—as usually understood at the present time—when applied to moving bodies, leads to asymmetries which do not appear to be inherent in the phenomena.

Examples of this sort, together with unsuccessful attempts to discover any motion of the earth relative to the "light medium," suggest that the phenomena of electrodynamics as well as of mechanics possess no properties corresponding to the idea of absolute rest.