McCarthyism

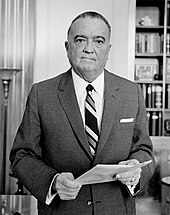

Defunct Newspapers Journals TV channels Websites Other Congressional caucuses Economics Gun rights Identity politics Nativist Religion Watchdog groups Youth/student groups Miscellaneous Other Personal ideologies Nationalisms McCarthyism, also known as the Second Red Scare, was the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage in the United States during the late 1940s through the 1950s.

[2][3] The U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren made a series of rulings on civil and political rights that overturned several key laws and legislative directives, and helped bring an end to the Second Red Scare.

Following the breakdown of the wartime East-West alliance with the Soviet Union, and with many remembering the First Red Scare, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order in 1947 to screen federal employees for possible association with organizations deemed "totalitarian, fascist, communist, or subversive", or advocating "to alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means."

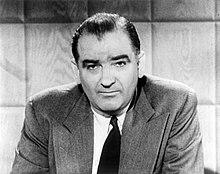

In a speech in February 1950, McCarthy claimed to have a list of members of the Communist Party USA working in the State Department, which attracted substantial press attention, and the term McCarthyism was published for the first time in late March of that year in The Christian Science Monitor, along with a political cartoon by Herblock in The Washington Post.

In the early 21st century, the term is used more generally to describe reckless and unsubstantiated accusations of treason and far-left extremism, along with demagogic personal attacks on the character and patriotism of political adversaries.

Most of these reprisals were initiated by trial verdicts that were later overturned,[8] laws that were later struck down as unconstitutional,[9] dismissals for reasons later declared illegal[10] or actionable,[11] and extra-judiciary procedures, such as informal blacklists by employers and public institutions, that would come into general disrepute, though by then many lives had been ruined.

Following the end of the Cold War, unearthed documents revealed substantial Soviet spy activity in the United States, though many of the agents were never properly identified by Senator McCarthy.

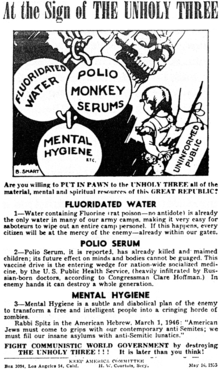

Many factors contributed to McCarthyism, some of them with roots in the First Red Scare (1917–20), inspired by communism's emergence as a recognized political force and widespread social disruption in the United States related to unionizing and anarchist activities.

Owing in part to its success in organizing labor unions and its early opposition to fascism, and offering an alternative to the ills of capitalism during the Great Depression, the Communist Party of the United States increased its membership through the 1930s, reaching a peak of about 75,000 members in 1940–41.

[16] Although the Igor Gouzenko and Elizabeth Bentley affairs had raised the issue of Soviet espionage in 1945, events in 1949 and 1950 sharply increased the sense of threat in the United States related to communism.

In Britain, Klaus Fuchs confessed to committing espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union while working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory during the War.

The more conservative politicians in the United States had historically referred to progressive reforms, such as child labor laws and women's suffrage, as "communist" or "Red plots", trying to raise fears against such changes.

"[23] A number of anti-communist committees, panels, and "loyalty review boards" in federal, state, and local governments, as well as many private agencies, carried out investigations for small and large companies concerned about possible Communists in their work forces.

One of the most common causes of suspicion was membership in the Washington Bookshop Association, a left-leaning organization that offered lectures on literature, classical music concerts, and discounts on books.

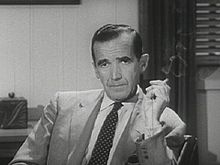

In October 1947, the committee began to subpoena screenwriters, directors, and other movie-industry professionals to testify about their known or suspected membership in the Communist Party, association with its members, or support of its beliefs.

[53] On November 25, 1947, the day after the House of Representatives approved citations of contempt for the Hollywood Ten, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, issued a press release on behalf of the heads of the major studios that came to be referred to as the Waldorf Statement.

According to historian Richard G. Powers, McCarthy added "bogus specificity" to "sweeping accusation[s]", gaining support among "countersubversive anticommunists" on one hand, who sought to find and punish perceived communists.

Furthermore, based on later declassified evidence, "The paradoxical lesson from several decades of scholarship is that the same organization that inspired democratic idealists in the pursuit of social justice also was secretive, authoritarian, and morally compromised by ties to the Stalin regime.

Many of the hearings and trials of McCarthyism featured testimony by former Communist Party members such as Elizabeth Bentley, Louis Budenz, and Whittaker Chambers, speaking as expert witnesses.

[87] After the extremely damaging "Cambridge Five" spy scandal (Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross), suspected homosexuality was also a common cause for being targeted by McCarthyism.

[92] However, in the context of the highly politicized Cold War environment, homosexuality became framed as a dangerous, contagious social disease that posed a potential threat to state security.

A port-security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination.

[97] Some of the notable people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism include: In 1953, Robert K. Murray, a young professor of history at Pennsylvania State University who had served as an intelligence officer in World War II, was revising his dissertation on the Red Scare of 1919–20 for publication until Little, Brown and Company decided that "under the circumstances ... it wasn't wise for them to bring this book out."

On one occasion he warned that many local anti-communist movements constituted a "general attack not only on schools and colleges and libraries, on teachers and textbooks, but on all people who think and write ... in short, on the freedom of the mind".

Harry Slochower was a professor at Brooklyn College who had been fired by New York City for invoking the Fifth Amendment when McCarthy's committee questioned him about his past membership in the Communist Party.

Guilt or innocence may turn on what Marx or Engels or someone else wrote or advocated as much as a hundred years or more ago… When the propriety of obnoxious or unfamiliar view about government is in reality made the crucial issue, …prejudice makes conviction inevitable except in the rarest circumstances.

"[160][161] In its 1958 decision in Kent v. Dulles, the Supreme Court halted the State Department from using the authority of its own regulations to refuse or revoke passports based on an applicant's communist beliefs or associations.

As Moynihan put it, "reaction to McCarthy took the form of a modish anti-anti-Communism that considered impolite any discussion of the very real threat Communism posed to Western values and security."

[169] The opposing view holds that, recent revelations notwithstanding, by the time McCarthyism began in the late 1940s, the CPUSA was an ineffectual fringe group, and the damage done to U.S. interests by Soviet spies after World War II was minimal.

In The Age of Anxiety: McCarthyism to Terrorism, author Haynes Johnson compares the "abuses suffered by aliens thrown into high-security U.S. prisons in the wake of 9/11" to the excesses of the McCarthy era.