Mutualism (economic theory)

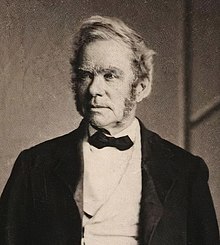

It first developed a practical expression in Josiah Warren's community experiments in the United States, which he established according to the principles of equitable commerce based on a system of labor notes.

[20] By the 1850s, Warren himself had moved on from Ohio and established the Utopian Community of Modern Times on Long Island, New York,[21] but his mutualist experiments would decline with the outbreak of the American Civil War.

[35] Proudhon's anti-capitalist economic theories stood in sharp contrast to liberal economists of the time, such as Frédéric Bastiat and Henry Charles Carey, who argued in defense of landlords and capitalists from the claims of workers.

[41] During the early 1860s, the French anarchist movement first began to develop an organised expression, establishing trade unions and mutual credit systems inspired by Proudhon's mutualist theories.

But in the following years, French mutualists began to lose control over the organisation to Russian and German communists based in Belgium,[41] and mutualism was gradually overshadowed by other anarchist schools of thought.

[49] By the 1870s, as divisions between the Marxists and the anti-authoritarians in the IWA grew sharper, Proudhonian mutualism gradually lost its remaining influence; although it continued to see minor developments by collectivists such as César De Paepe and Claude Pelletier,[50] as well as in the programme of the Paris Commune of 1871.

[53] Warren's mutualist experiments, which inspired the American individualism of Lysander Spooner and Stephen Pearl Andrews,[57] laid a foundation for the introduction of Proudhonian mutualism to the country.

[60] Proudhonian mutualism was later discussed in articles by a number of American utopian theorists, including Francis George Shaw, Albert Brisbane and Charles Anderson Dana.

[61] Two of the most important figures of this period were Joshua K. Ingalls and William Batchelder Greene,[62] who were inspired by Proudhon's mutualist ideas as elaborated by Dana,[63] synthesising it with American individualist traditions pioneered by Warren.

[71] In 1869, Ezra and Angela Heywood established the New England Labor Reform League (NELRL), which published the individualist anarchist magazine The Word and widely distributed the works of American mutualists such as Warren and Greene, who were also members of the organisation.

[59] From 1872 to 1876, the NELRL attempted to lobby the Massachusetts General Court to establish a mutual bank, but they were ultimately unsuccessful,[72] convincing them that state legislatures had already undergone regulatory capture by capitalists.

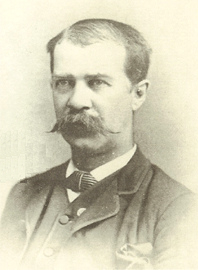

[70] Inspired by the older mutualists within the NELRL, the young League member Benjamin Tucker quickly rose to prominence as one of the leading figures of individualist anarchism in the United States.

[77] In order to combat coercive practices that allowed the proliferation of wealth and privilege, Tucker proposed the establishment of a "free market of anarchistic socialism", in which all forms of monopoly were abolished.

[82] Tucker's followers dedicated themselves to elaborating mutualist projects, with Alfred B. Westrup, Herman Kuehn and Clarence Lee Swartz all writing extensively on the subject of mutual credit.

[83] By the beginning of the Gilded Age, Proudhonian mutualism was firmly identified with American individualism,[84] while Tucker's followers came to define themselves in opposition to anarchist communism.

[83] One of Tucker's disciples, Dyer Lum, attempted to bridge the divide between the American individualists and the growing labour movement, which was developing sympathies for social anarchism.

[85] In the 1880s, Lum joined the International Working People's Association (IWPA), in which he developed a laissez-faire analysis of "wage slavery" that proposed a form of occupation and use property rights and a mutual banking system.

[86] Over the years, Lum worked to develop ties between different radical tendencies, hoping to create a "pluralistic anarchistic coalition" capable of advancing a social revolution.

[87] By the time of the Haymarket affair, Lum had aligned with the IWPA's view of labor unions as a means to both combat the exploitation of labour and to prefigure a future free association of producers.

In the 1890s, Lum joined the American Federation of Labor (AFL), within which he introduced workers' to mutualist ideas on banking, land reform and cooperativism through his pamphlet The Economics of Anarchy.

[90] But factional divides also began to exacerbate at this time, as Tucker's individualist group in Boston and immigrant revolutionary socialists in Chicago split into opposing camps, while Lum attempting to mend relations between the two.

[91] But eventually the split drove many of Tucker's disciples away from the anarchist movement and towards right-wing politics, with some like Clarence Lee Swartz coming to embrace capitalism and setting the groundwork for modern American libertarianism.

[44] Gustav Landauer, who became a leading figure in the Bavarian Soviet Republic during the German Revolution of 1918–1919, adopted a mutualist programme of mutual credit, equal exchange and usufruct property rights.

[95] By the end of the 20th century, mutualism had largely fallen out of the popular consciousness, only experiencing a revival in interest when the internet improved public access to old texts.

Carson's Studies in Mutualist Political Economy proposed a synthesis of Austrian and Marxian economics, developing a form of "free-market anti-capitalism" based on Tucker's conception of mutualism.

We want these associations to be models for agriculture, industry and trade, the pioneering core of that vast federation of companies and societies woven into the common cloth of the democratic social Republic".

[100] In What Is Mutualism?, Clarence Lee Swartz wrote: It is, therefore, one of the purposes of Mutualists, not only to awaken in the people the appreciation of and desire for freedom, but also to arouse in them a determination to abolish the legal restrictions now placed upon non-invasive human activities and to institute, through purely voluntary associations, such measures as will liberate all of us from the exactions of privilege and the power of concentrated capital.

Proudhon described it as follows: Beneath the governmental machinery, in the shadow of political institutions, out of the sight of statesmen and priests, society is producing its own organism, slowly and silently; and constructing a new order, the expression of its vitality and autonomy.

[112] Like other anarcho-communists, Peter Kropotkin advocated the abolition of labour remuneration and questioned, "how can this new form of wages, the labor note, be sanctioned by those who admit that houses, fields, mills are no longer private property, that they belong to the commune or the nation?

"[113] According to George Woodcock, Kropotkin believed that a wage system, whether "administered by Banks of the People or by workers' associations through labor cheques", is a form of compulsion.