Assassination of William McKinley

William McKinley, the 25th president of the United States, was shot on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition in the Temple of Music in Buffalo, New York, on September 6, 1901, six months into his second term.

Secretary to the President George B. Cortelyou feared that an assassination attempt would take place during a visit to the Temple of Music and took it off the schedule twice, but McKinley restored it each time.

Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed in the electric chair, and Congress passed legislation to officially charge the Secret Service with the responsibility for protecting the president.

McKinley led the nation both to a return to prosperity and to victory in the Spanish–American War in 1898, taking possession of such Spanish colonies as Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

Re-elected handily in a rematch against Bryan in 1900, according to historian Eric Rauchway, "it looked as if the McKinley Administration would continue peaceably unbroken for another four years, a government devoted to prosperity".

[6] By 1901, this movement was feared in the United States – New York's highest court had ruled that the act of identifying oneself as an anarchist in front of an audience was a breach of the peace.

[13][14] McKinley, his wife Ida, and their official party left Washington on April 29 for a tour of the nation by train, scheduled to conclude in Buffalo for a speech on what had been designated as "President's Day".

The cannon that fired a salute to the President on his arrival in the city had been set too close to the track, and the explosions blew out several windows in the train, unnerving the First Lady.

"[24] As William McKinley stepped down from the train to the official welcome, Czolgosz shoved his way forward in the crowd, but found the President too well guarded to make an attempt on his life.

[23] McKinley's trip to Buffalo was part of a planned ten-day absence from Canton, beginning on September 4, 1901, which was to include a visit in Cleveland to an encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic; he was a member as a Union veteran.

[26][27] Upon arrival in Buffalo, the presidential party was driven through the fairgrounds on the way to the Milburn House, pausing for a moment at the Triumphal Bridge at the Exposition so the visitors could look upon the fair's attractions.

McKinley restored it every time; he wished to support the fair (he agreed with its theme of hemispheric cooperation), enjoyed meeting people, and was not afraid of potential assassins.

[26] On the morning of Thursday, September 5, the fair gates were opened at 6:00 a.m. to allow the crowds to enter early and seek good spots to witness the President's speech.

The route between the Milburn House and the site of the speech was packed with spectators; McKinley's progress by carriage to the fair with his wife was accompanied by loud cheering.

"[31] The crowd greeted his speech with loud applause; at its conclusion, the President escorted Ida McKinley back to her carriage as she was to return to the Milburn House while he saw the sights at the fair.

He was heavily guarded by soldiers and police, but still tried to interact with the public, encouraging those who tried to run to him by noticing them, and bowing to a group of loud young popcorn sellers.

Czolgosz also rose early with the intent of lining up for the public reception at the Temple of Music; he reached the Exposition gates at 8:30 a.m., in time to see the President pass in his carriage en route to the train station for the visit to Niagara Falls.

It was a hot day, and Ida McKinley felt ill due to the heat; she was driven to the International Hotel to await her husband, who toured Goat Island before joining his wife for lunch.

[37] When given the opportunity to host a public reception for President McKinley, fair organizers chose to site it in the Temple of Music – Louis L. Babcock, grand marshal of the Exposition, regarded the building as ideal for the purpose.

Cortelyou anxiously watched the time; about halfway through the ten minutes allotted, he sent word to Babcock to have the doors closed when the presidential secretary raised his hand.

The procession of citizens shaking hands with their President was interrupted when 12-year-old Myrtle Ledger of Spring Brook, New York, who was accompanied by her mother, asked McKinley for the red carnation he always wore on his lapel.

The Secret Service men looked suspiciously on a tall, swarthy man who appeared restless as he walked towards the President, but he shook hands with McKinley without incident and began to move towards the exit.

My Dearest was receiving in a public hall on our return, when he was shot by a ... "[61] Leech, in her biography of President McKinley, suggests that the First Lady could not write the word, "anarchist".

It was not used on the President; sources vary on why this was – Leech stated that the machine, which she says was procured by Cortelyou and accompanied by a trained operator, was not used on orders of the doctors in charge of McKinley's case.

Urgent word to return to Buffalo was sent to Vice President Roosevelt, 12 mi (19 km) from the nearest telegraph or telephone in the Adirondack wilderness; a park ranger was sent to find him.

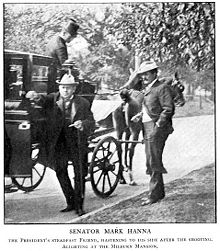

Morgan recounts their final encounter, "Sometime that terrible evening, Mark Hanna had approached the bedside, tears standing in his eyes, his hands and head shaking in disbelief that thirty years of friendship could end thus.

[79] At the time of McKinley's death, Roosevelt was on his return journey to Buffalo, racing over the mountain roads by carriage to the nearest railroad station, where a special train was waiting.

A death mask was taken, and private services took place in the Milburn House before the body was moved to Buffalo City and County Hall for the start of five days of national mourning.

Modern scholars generally believe that McKinley died of pancreatic necrosis, a condition that is difficult to treat today and would have been completely impossible for the doctors of his time.

In his 27-minute address to the jury, Lewis took pains to praise President McKinley; Miller notes that the closing argument was more calculated to defend the attorney's "place in the community, rather than an effort to spare his client the electric chair".