Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence

It was supposedly signed on May 20, 1775, in Charlotte, North Carolina, by a committee of citizens of Mecklenburg County, who declared independence from Great Britain after hearing of the battle of Concord.

Each militia company in Mecklenburg County had sent two delegates to the meeting, where measures were to be discussed regarding the ongoing dispute between the British Empire and the American colonies.

The North Carolina congressional delegation—Richard Caswell, William Hooper, and Joseph Hewes—told Jack that although they supported what had been done, it was premature to discuss a declaration of independence in Congress.

[5] Alexander concluded by writing that although the original documents relating to the Mecklenburg Declaration were destroyed in a fire in 1800, the article was written from a true copy of the papers left to him by his father, who was now deceased.

The now elderly witnesses did not agree in every detail, but they generally corroborated the story that a declaration of independence had been read in public in Charlotte, although they were not all certain about the date.

Perhaps most importantly, eighty-eight-year-old Captain James Jack was still living, and he confirmed that he had delivered to the Continental Congress a declaration of independence that had been adopted in May 1775.

[citation needed] After 1819, people in North Carolina (and Tennessee, which shared an early history) began to take pride in the previously unheralded Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.

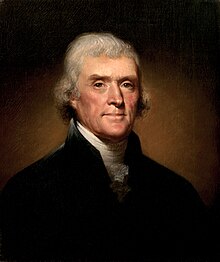

According to author Hoyt, Jefferson used the term to mean that Hooper had been conservative on declaring independence, not to imply that he had been a Loyalist, but North Carolinians felt their honored Patriots had been slighted.

[22] The state of North Carolina responded to Jefferson's letter in 1831 with an official pamphlet that reprinted the previously published accounts with some additional testimony in support of the Mecklenburg Declaration.

Jones defended the patriotism of William Hooper and accused Jefferson of being envious that a little county in North Carolina had declared independence at a time when the "Sage of Monticello" was still hoping for reconciliation with Great Britain.

[26] Hawks's position was apparently supported by the discovery of a proclamation by Josiah Martin, the last royal governor of North Carolina, which seemed to confirm the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration.

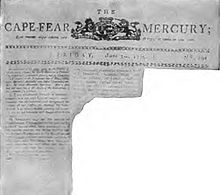

In August 1775, Governor Martin had written that he had: seen a most infamous publication in the Cape Fear Mercury importing to be resolves of a set of people styling themselves a committee for the county of Mecklenburg, most traitorously declaring the entire dissolution of the laws, government, and constitution of this country, and setting up a system of rule and regulation repugnant to the laws and subversive of his majesty's government....[27]Here, at last, was contemporaneous confirmation that radical resolves had been adopted in Mecklenburg County in 1775.

In 1905, Collier's Magazine published what was said to be a clipping from the missing issue, but advocates and opponents of the Mecklenburg Declaration agreed that the document was a hoax.

[32] In an influential article in the North Carolina University Magazine, Dr. Phillips concluded that John McKnitt Alexander had admitted to having reconstructed the text of the Mecklenburg Declaration from memory in 1800.

[clarification needed][33] In 1906, William Henry Hoyt published a scholarly work that many historians have regarded as the conclusive refutation of the Mecklenburg Declaration.

Hoyt's argument is briefly as follows: After the original documents relating to the Mecklenburg Resolves were destroyed by fire in 1800, John McKnitt Alexander attempted to recreate them from memory.

The eyewitnesses were misled into accepting the text of the Mecklenburg Declaration as authentic because it had been published in 1819 with the claim that it was a true copy of the original resolutions.

While they undoubtedly told the truth about the events of May 1775 as they remembered them, their testimony was given in response to leading questions, and their answers actually referred to the lost Mecklenburg Resolves.

This argument was developed in the 20th century by Professor Archibald Henderson of the University of North Carolina, who, beginning in 1916, wrote numerous articles on the subject.

The entry is unsigned and undated, but internal evidence suggests that it was written in 1783 in Salem, North Carolina, by a merchant named Traugott Bagge.

Jones, in his North Carolina Illustrated (Chapel Hill: University of N.C. Press, 1983), pointedly places ironic quotation marks around the name of the declaration.

"[47] In 1997 historian Pauline Maier wrote: When compared to other documents of the time, the "Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence" supposedly adopted on May 20, 1775, is simply incredible.

[48]Despite much scholarly opinion against the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration, belief in the document remains important to some North Carolinians, says historian Dan L. Morrill, who notes that the possibility that it is genuine cannot be entirely discounted.

A monument to the reputed signers of the declaration was unveiled in Charlotte on May 20, 1898, and a commemorative tablet was placed in the rotunda of the North Carolina State Capitol building on May 20, 1912.

Four United States presidents visited Charlotte to participate in the Mecklenburg Day celebration: William Howard Taft (1909), Woodrow Wilson (1916), Dwight D. Eisenhower (1954), and Gerald Ford (1975).

Aware of the controversy, the presidents generally praised the revolutionary patriots of Mecklenburg County without specifically endorsing the authenticity of the disputed document.