Meigs Elevated Railway

He served as captain of the Union Army during the American Civil War, and he made a personal appeal to President Lincoln for permission to raise a detachment of black troops for a colored artillery battery.

There he became close friends with a fellow veteran, General Benjamin Butler, and the two moved together to Lowell, Massachusetts, where they built adjacent houses.

As a result of exploiting his social connections in Massachusetts, he attracted substantial backing, including that of his friend General Butler.

[8] It then began to lobby for a state charter to allow it to build rapid transit lines in the streets of Boston and its suburbs.

The text included the following proviso: No location for tracks shall be petitioned for in the city of Boston, until at least one mile of the road has been built and operated, nor until the safety and strength of the structure and the rolling stock and motive power shall have been examined and approved by the board of railroad commissioners or by a competent engineer to be appointed by them.Meigs amended his design, and he acquired a new patent in 1885.

[11] The company raised $20,000 cash (about $500,000 in 2020 values),[12] which was enough to build a full-sized experimental model comprising a short section of the elevated railway.

The 227-foot (69 metre) iron demonstration line was erected on land abutting company headquarters in Bridge Street, and was opened to paying riders in June 1886.

[15] The short length of demonstration line in iron was connected to the car shed by a longer wooden version, intended to test the capabilities of the system.

[16] In July 1886, the Scientific American magazine published an article entitled The Meigs Elevated Railway and containing this assertion: Everything has worked in the most satisfactory manner, the train rounding the exceedingly sharp curves easily, and mounting the steep grades without trouble.A fire, supposedly the result of arson, broke out on the night of February 4, 1887, and destroyed Meigs's car shed as well as burning out the experimental coach.

The Lake Street Elevated Railroad of Chicago intended to use it when chartered in 1888, but changed its policy and settled on a conventional design before beginning construction.

In 1893, he published a booklet entitled True Rapid Transit wherein he rejected both the building of subways and the use of electric power, insisting that steam engines were more economical.

Joseph V. Meigs, inventor and entrepreneur, successfully tested a steam-powered elevated monorail train intended for rapid transit use in Boston.

Joe Meigs's extensive collection of papers and drawings relating to the system, as well as correspondence and genealogical material, is held at the Manuscripts and Archives Department of the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University.

[32] The following description is based on a plan, with annotations, published in The Meigs Railway System: The Reasons For Its Departures From The Ordinary Practice, page 177.

The line then ran west parallel to the north side of the car shed, before turning on a 45 degree curve before continuing south-west across the street to its terminus.

[35] The line had differing construction techniques: The Meigs system had a three-rail competitor proposed for Boston between 1888 and 1891, and discussed by the Massachusetts state legislature.

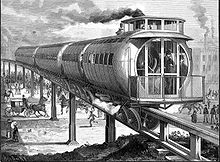

[16] The basic premise for the design of the system was to make the street-level footprint of the line as narrow as possible, to ameliorate the problem of shadowing created by conventional urban elevated railroads.

The center of gravity of the cars and engine is brought down as low as possible, thereby lessening the effect of leverage caused by wind pressure.

The smooth, even surface of the exterior of the entire train serve to decrease the resistance to the wind, and permits a high rate of speed.The following description is for the expected standard iron construction.

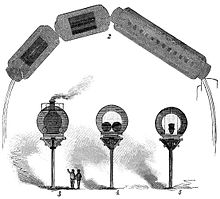

The permanent way on which the trains were to run consisted, firstly of a line of single iron structural support girders on the tops of the pillars.

A pair of U-shaped girders, facing upwards, was bolted to the sides of each track beam, and filled with longitudinal baulks of timber.

Neither the experimental line nor published illustrations gave any indications as to how routine inspection and maintenance of the permanent way were to have been carried out, without recourse to ladders or scaffolding erected in the street below.

The cylindrical car body was formed of hoops of light iron T-bars bent into a circle of diameter 10.7 feet (3.26 metres).

There is an entire absence of sharp corners, so that, in case of a serious accident, the liability of the passenger being greatly injured is largely avoided.There is no mention of any insulation, or of heating arrangements for winter.

Despite the reference to copper sheathing, the surviving photo of the fire damage indicates that the metal used in the experimental car was cheaper, with a lower melting point.

The ends had open platforms for entry and exit, with canopies, and passengers passed into the body of the car via swing doors with glass panels and spring closures.

Turning engines and marshalling trains to have the locomotive in front would have been very challenging to the system (the experimental line had no turntable), and running in reverse half the time would have been desirable.

The crown sheet was arched, and inclined downward at the back end to allow of climbing and descending grades equal to 15% without exposing any uncovered part to the fire (and so causing an explosion).

The piston rods connected with independent crossheads gliding upon steel girders, supported at their ends by standards bolted to the floor beams.

The boxes slid in cast iron runners placed at right angle to the line of the engine, and each axle had a crank keyed upon its upper end.