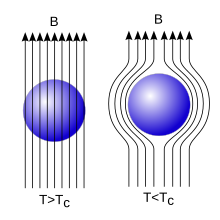

Meissner effect

The German physicists Walther Meißner (anglicized Meissner) and Robert Ochsenfeld[1] discovered this phenomenon in 1933 by measuring the magnetic field distribution outside superconducting tin and lead samples.

The ability for the expulsion effect is determined by the nature of equilibrium formed by the neutralization within the unit cell of a superconductor.

Any perfect conductor will prevent any change to magnetic flux passing through its surface due to ordinary electromagnetic induction at zero resistance.

Superconductors in the Meissner state exhibit perfect diamagnetism, or superdiamagnetism, meaning that the total magnetic field is very close to zero deep inside them (many penetration depths from the surface).

In normal materials diamagnetism arises as a direct result of the orbital spin of electrons about the nuclei of an atom induced electromagnetically by the application of an applied field.

In superconductors the illusion of perfect diamagnetism arises from persistent screening currents which flow to oppose the applied field (the Meissner effect); not solely the orbital spin.

The discovery of the Meissner effect led to the phenomenological theory of superconductivity by Fritz and Heinz London in 1935.

This theory explained resistanceless transport and the Meissner effect, and allowed the first theoretical predictions for superconductivity to be made.

However, this theory only explained experimental observations—it did not allow the microscopic origins of the superconducting properties to be identified.

[6] The Meissner superconductivity effect serves as an important paradigm for the generation mechanism of a mass M (i.e., a reciprocal range,

In fact, this analogy is an abelian example for the Higgs mechanism,[7] which generates the masses of the electroweak W± and Z gauge particles in high-energy physics.