Superconducting magnet

To keep the helium from boiling away, the cryostat is usually constructed with an outer jacket containing (significantly cheaper) liquid nitrogen at 77 K. Alternatively, a thermal shield made of conductive material and maintained in 40 K – 60 K temperature range, cooled by conductive connections to the cryocooler cold head, is placed around the helium-filled vessel to keep the heat input to the latter at acceptable level.

[citation needed] Because of increasing cost and the dwindling availability of liquid helium, many superconducting systems are cooled using two stage mechanical refrigeration.

In general two types of mechanical cryocoolers are employed which have sufficient cooling power to maintain magnets below their critical temperature.

These have a Tc of 18 K. When operating at 4.2 K they are able to withstand a much higher magnetic field intensity, up to 25 T to 30 T. Unfortunately, it is far more difficult to make the required filaments from this material.

High-temperature superconductors (e.g. BSCCO or YBCO) may be used for high-field inserts when required magnetic fields are higher than Nb3Sn can manage.

[citation needed] The coil windings of a superconducting magnet are made of wires or tapes of Type II superconductors (e.g.niobium–titanium or niobium–tin).

These filaments need to be this small because in this type of superconductor the current only flows in a surface layer whose thickness is limited to the London penetration depth (see Skin effect).

The coil must be carefully designed to withstand (or counteract) magnetic pressure and Lorentz forces that could otherwise cause wire fracture or crushing of insulation between adjacent turns.

The windings become a closed superconducting loop, the power supply can be turned off, and persistent currents will flow for months, preserving the magnetic field.

The short circuit is made by a 'persistent switch', a piece of superconductor inside the magnet connected across the winding ends, attached to a small heater.

To go to persistent mode, the supply current is adjusted until the desired magnetic field is obtained, then the heater is turned off.

The winding current, and the magnetic field, will not actually persist forever, but will decay slowly according to a normal inductive time constant (L/R): where

A quench is an abnormal termination of magnet operation that occurs when part of the superconducting coil enters the normal (resistive) state.

When this happens, that particular spot is subject to rapid Joule heating from the enormous current, which raises the temperature of the surrounding regions.

The entire magnet rapidly becomes normal (this can take several seconds, depending on the size of the superconducting coil).

This is accompanied by a loud bang as the energy in the magnetic field is converted to heat, and rapid boil-off of the cryogenic fluid.

If a large magnet undergoes a quench, the inert vapor formed by the evaporating cryogenic fluid can present a significant asphyxiation hazard to operators by displacing breathable air.

Wernick made the discovery that a compound of niobium and tin could support critical-supercurrent densities greater than 100,000 amperes per square centimetre in magnetic fields of 8.8 teslas.

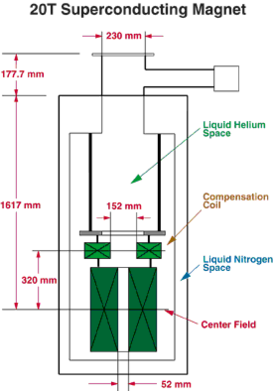

[11] Despite its brittle nature, niobium–tin has since proved extremely useful in supermagnets generating magnetic fields up to 20 T. The persistent switch was invented in 1960 by Dwight Adams while a postdoctoral associate at Stanford University.

Although niobium–titanium alloys possess less spectacular superconducting properties than niobium–tin, they are highly ductile, easily fabricated, and economical.

In 1986, the discovery of high temperature superconductors by Georg Bednorz and Karl Müller energized the field, raising the possibility of magnets that could be cooled by liquid nitrogen instead of the more difficult-to-work-with helium.

In 2019, a new world-record of 32.35 T with all-superconducting magnet is achieved by Institute of Electrical Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IEE, CAS).

[21] In 2022, the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (HFIPS, CAS) claims new world record for strongest steady magnetic field of 45.22 T reached,[22][23] while the previous NHMFL 45.5 T record in 2019 was actually reached when the magnet failed immediately in a quench.

They can be smaller, and the area at the center of the magnet where the field is created is empty rather than being occupied by an iron core.