Melchior Lorck

[2] His earliest engravings stem from the years before the travel stipend, starting with rather unsecure copies after Heinrich Aldegrever, but soon developing a fine control of the burin as in the staunchly anti-papal The Pope as a Wild Man Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine from 1545 and the Portrait of Martin Luther from 1548.

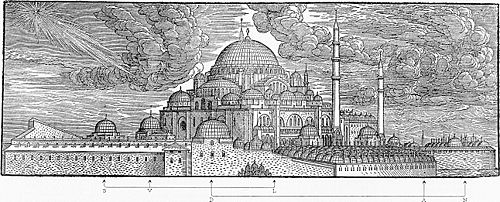

In 1555 Lorck was assigned to the embassy that the German king Ferdinand I (from 1556 Holy Roman Emperor) sent to the so-called Sublime Porte, the court of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in Constantinople (Istanbul).

In 1555 at the caravanserai, the Elçi Hanı, Lorck produced engraved portraits of Busbecq and his co-envoys, Ferenc Zay Archived 2020-01-10 at the Wayback Machine and Antun Vrančić (Antonius Verantius), a few drawings of animals and a view over the rooftops of the city from one of the top windows of the lodging.

In the periods of greater freedom however, he would draw ancient and modern monuments of the city, as well as the customs and dresses of the various peoples gathered from all parts of the Ottoman Empire.

At the end of his sojourn, he must have been spending extensive time with the Turkish military, as he was later able to portray a large number of different ranks and nationalities in the Ottoman army.

[5] While in Vienna, Melchior Lorck was contacted both by the brother of the late king Christian III, duke Hans the Elder of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev who demanded his service.

While finally answering the duke in January 1563, he also sent King Frederik II a letter, containing a lengthy description of his career up to the date.

[6] In 1562 Melchior Lorck had produced the large engraved bust portraits of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and the Persian envoy in Constantinople, Ismaïl, which he added to his letters.

Around the same time, Lorck was employed as Hartschier (from Italian: arciere), an honorary position with an annual salary in the horse guard of the emperor that he would keep until 1579.

In December that year the emperor, Maximilian, wrote a rather unusual letter to his “cousin” (i.e. cousin in office), King Frederik II, asking him to receive Melchior Lorck well, as Lorck was to go to Denmark to collect the inheritance after his eldest brother, Caspar, who had been killed in the Northern Seven Years' War between Denmark and Sweden.

[10] Initially, Lorck was employed as cartographer, mapping the lower streams of the river Elbe, from Geesthacht to the sea, in order to support Hamburg's legal claims to the stable rights in a dispute with its neighbor Brunswick-Lüneburg.

In Lorck's testament, one of the only glimpses of a family life shines through as he leaves everything to a certain widow, Anna Schrivers, whom he describes as his betrothed bride.

He was one of the first to write an entry into the album amicorum of Abraham Ortelius, and befriended the publisher and engraver Philip Galle, who dedicated Hans Vredeman de Vries’s book about wells and fountains to him.

The book, the only known copy of which perished in the firestorms in Hamburg in June 1943, caused by the allied forces' Operation Gomorrha, contained two bust portraits and two full-length portraits of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and of the Persian envoy to the High Porte, Ismaïl, still known today, as well as accompanying poems by Conrad Leicht and Paulus Melissus.

In a letter to the Danish king, Frederik II, of May 19, 1575,[19] he indicated that he had problems financing his publication and asked for economic support to this end.

The leading Lorck-scholar, Dr. Erik Fischer, the former keeper of the Copenhagen Printroom, suggests that the Turkish Publication came out only as a torso of what it was intended to be.

It is Dr. Fischer's thesis that that "original" was a written manuscript that would supplement the woodcuts and thus fulfil the promise given in the 1574 Soldan Soleyman... of a thorough description of Turkish society, life and customs.

[22] When the application was dismissed by the emperor, now Rudolph II, he instead applied in 1579 for a pension and relief from duty as ‘’Hartschier’’, both granted graciously.

[27][28] Melchior Lorck was well known at the end of the 16th century and mentioned by e.g. Karel van Mander in the Schilder-boeck, even if he did not get a chapter of his own.

Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst , Department of Prints and Drawings, inv. no. KKSgb6141

Copenhagen, The Royal Library