European Free Trade Association

The Stockholm Convention (1960), to establish the EFTA, was signed on 4 January 1960 in the Swedish capital by seven countries (known as the "Outer Seven": Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom).

The other five, Austria, Denmark, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom, had joined the EU at some point in the intervening years.

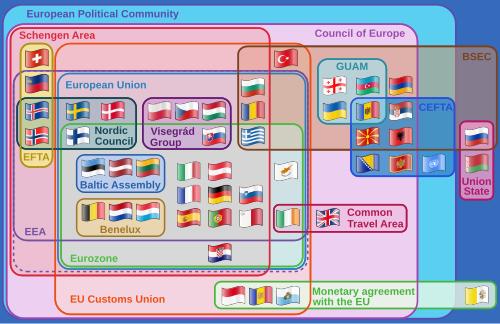

[4] As a result, its member states have jointly concluded free trade agreements with the EU and a number of other countries.

The founding members of the EFTA were: Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

[11] Between 1994 and 2011, EFTA memberships for Andorra, San Marino, Monaco, the Isle of Man, Turkey, Israel, Morocco, and other European Neighbourhood Policy partners were discussed.

In response, the Council requested that negotiations with the three microstates on further integration continue, and that a report be prepared by the end of 2013 detailing the implications of the two viable alternatives and recommendations on how to proceed.

[21] Espen Barth Eide, Støre's successor, responded to the commission's report in late 2012 by questioning whether the microstates have sufficient administrative capabilities to meet the obligations of EEA membership.

However, he stated that Norway would be open to the possibility of EFTA membership for the microstates if they decided to submit an application, and that the country had not made a final decision on the matter.

[24] On 18 November 2013, the EU Commission concluded that "the participation of the small-sized countries in the EEA is not judged to be a viable option at present due to the political and institutional reasons", and that Association Agreements were a more feasible mechanism to integrate the microstates into the internal market.

On 16 July 2009, the government of Iceland formally applied for EU membership,[27] but the negotiation process was suspended in mid-2013, and in 2015 the foreign ministers wrote to withdraw its application.

A 2013 research paper presented to the Parliament of the United Kingdom proposed a number of alternatives to EU membership which would continue to allow it access to the EU's internal market, including continuing EEA membership as an EFTA member state, or the Swiss model of a number of bilateral treaties covering the provisions of the single market.

[32] In the first meeting since the Brexit vote, EFTA reacted by saying both that they were open to a UK return, and that Britain has many issues to work through.

Norway's European affairs minister, Elisabeth Vik Aspaker, told the Aftenposten newspaper: "It's not certain that it would be a good idea to let a big country into this organization.

"[34] In late 2016, the Scottish First Minister said that her priority was to keep the whole of the UK in the European single market but that taking Scotland alone into the EEA was an option being "looked at".

(Nevertheless, Switzerland has multiple bilateral treaties with the EU that allow it to participate in the European Single Market, the Schengen Agreement and other programmes).

However, they also contribute to and influence the formation of new EEA relevant policies and legislation at an early stage as part of a formal decision-shaping process[citation needed].

However, during the negotiations for the EEA agreement, the European Court of Justice ruled by the Opinion 1/91 that it would be a violation of the treaties to give to the EU institutions these powers with respect to non-EU member states.

They were established in conjunction with the 2004 enlargement of the European Economic Area (EEA), which brought together the EU, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway in the Internal Market.

The EEA and Norway Grants are administered by the Financial Mechanism Office, which is affiliated to the EFTA Secretariat in Brussels.

The Citizens' Rights Directive[104] (also sometimes called the "Free Movement Directive") defines the right of free movement for citizens of the European Economic Area (EEA),[105] which includes the three EFTA members Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein plus the member states of the EU.

[108] It was to provide funding for the development of Portugal after the Carnation Revolution and the consequential restoration of democracy and the decolonization of the country's overseas possessions.

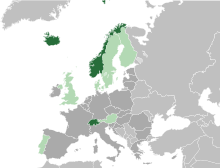

EFTA (green)