United Kingdom membership of the European Union

Since the foundation of the EEC, the UK had been an important neighbour and then a leading member state, until Brexit ended 47 years of membership.

The French president Charles De Gaulle was determined to have his own 'special relationship' with West Germany, for he wished the EEC to be essentially a Franco-German alliance, with the other four members being satellite states.

While it was true that Britain's economy, like many others, was struggling to recover from the high cost of the Second World War, De Gaulle had personal as well as economic reasons for not wanting the British around the table.

It provided for a single market for agricultural goods at guaranteed prices, a Community preference scheme against imports, and financial solidarity.

In the 1950s Britain's cheap food policy was predicated on trading at world market prices, which were throughout this period substantially lower than the CAP ones.

[2] Once de Gaulle had relinquished the French presidency in 1969, the UK made a third and successful application for membership (the CAP, and the Customs Union and Tariff system, being by now well established).

In France, government and business opinion were increasingly aware that American firms were dominating high-tech sectors and were better at organising integrated production networks in Europe than local companies, in part due to the fragmentation of European businesses, as argued by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber in his 1967 book Le défi américain ("The American Challenge").

In response, the country's main employers' organisation, the Conseil national du patronat français, lobbied along with senior French civil servants to reverse de Gaulle's policy regarding British membership.

[3] One complication with the negotiation came about because, in 1969 European Communities had asked their Foreign Affairs committee to 'study the best way of achieving progress in the matter of unification'.

[8] Despite having to wait until 1 January 1973 to become a member of the European Communities, the UK was allowed to take a full part in the political development in the days immediately after signing the treaty.

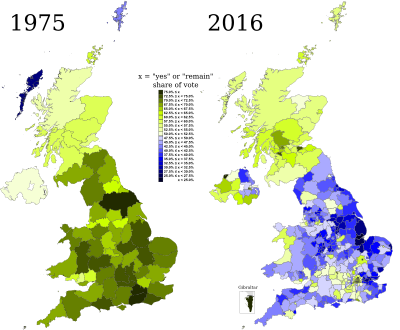

However, there were significant divides within the ruling Labour Party; a 1975 one-day party conference voted by two to one in favour of withdrawal,[12] and seven of the 23 cabinet ministers were opposed to EEC membership,[13] with Harold Wilson suspending the constitutional convention of Cabinet collective responsibility to allow those ministers to publicly campaign against the government.

In 1979, the United Kingdom opted out of the newly formed European Monetary System (EMS), which was the precursor to the creation of the euro currency.

[17] In 1985, the United Kingdom ratified the Single European Act – the first major revision to the Treaty of Rome – without a referendum, with the full support of the Thatcher government.

Thatcher resigned as Prime Minister in November 1990, amid internal divisions within the Conservative Party that arose partly from her increasingly Eurosceptic views.

The United Kingdom was forced to withdraw from the ERM in September 1992, after the pound sterling came under pressure from currency speculators (an episode known as Black Wednesday).

[23] It failed to win a single parliamentary seat because its vote was spread out across the country, and lost its deposit (funded by Goldsmith) in 505 constituencies.

[24] UKIP's electoral success in the 2014 European election has been documented as the strongest correlate of the support for the leave campaign in the 2016 referendum.

EU institutions are bound under article 6 of the Treaty on European Union to respect human rights under the convention,[27] over and above for example the Law of the United Kingdom.

[36] After Thatcher had negotiated the UK rebate of British membership payments in 1984, those favouring the EC and later the EU maintained a lead in the opinion polls, except during 2000 – at which time Prime Minister Tony Blair was aiming for closer EU integration, including adoption of the euro currency – and around 2011, as immigration into the United Kingdom became increasingly noticeable.

[36] As late as December 2015 there was, according to ComRes, a clear majority in favour of remaining in the EU, albeit with a warning that voter intentions would be considerably influenced by the outcome of Prime Minister David Cameron's ongoing EU reform negotiations, especially with regards to the two issues of "safeguards for non-Eurozone member states" and "immigration".

If the two parties were unable to strike an agreement, and if the Article 50 period had not been extended, the UK would leave the EU without a deal as the default position.

The newly established Eurosceptic Brexit Party, headed by Nigel Farage, made sweeping gains, taking a high percentage of the UK vote.

Negotiations on the future UK–EU relationship subsequently began once the UK formally left the EU and entered the transition period.