Mensural notation

An early form of mensural notation was first described and codified in the treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis ("The art of measured chant") by Franco of Cologne (c. 1280).

A much expanded system allowing for greater rhythmic complexity was introduced in France with the stylistic movement of the Ars nova in the 14th century, while Italian 14th-century music developed its own, somewhat different variant.

The decisive innovation of mensural notation was the systematic use of different note shapes to denote rhythmic durations that stood in well-defined, hierarchical numerical relations to each other.

The basic metrical relationship of a long to a short beat shifted from longa–breve in the 13th century, to breve–semibreve in the 14th, to semibreve–minim by the end of the 15th, and finally to minim–semiminim (i.e., half and quarter notes, or minim and crotchet) in modern notation.

Thus, the basic ascending B–L podatus shape was replaced by one where the second note was both folded out to the right and marked with an extra stem (), as if these two modifications were meant to cancel each other out.

In addition, the following rules hold for notes in all positions:[7] Mensural notation distinguished between several basic metric patterns of a piece of music, which were defined as combinations of ternary and binary subdivisions of time on successive hierarchical levels and roughly correspond to modern bar structures.

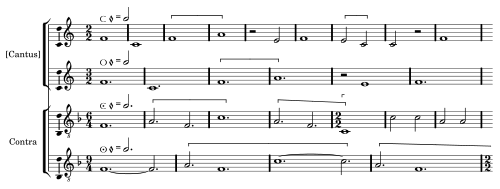

However, groups of longa rests at the beginning of a piece (which occurred frequently, as often some voices in a polyphonic composition would enter later than others) could be used as an indicator of the intended meter.

Beginning with Franco of Cologne, the same pattern was also applied between breves and semibreves,[10] and finally, with Philippe de Vitry's theory of the Ars nova, it was taken yet another level down, to the newly introduced minims.

Theorists developed an intricate set of precedence rules for when and how to apply imperfection, together with a complex terminology for its different types.

[11] Normally, a note was imperfected by one of the next smaller order, e.g., a breve (B) by a semibreve (Sb), and thereby lost one third of its own nominal value (ex.

The normal reading of the groups could be overridden by placing a separator dot (punctus divisionis) between the notes to indicate which of them were meant to form a ternary unit together (ex.

If the separator dot was placed after a potentially ternary note (e.g., a breve in tempus perfectum), it typically had the effect of keeping it perfect, i.e., overriding an imperfection that would otherwise have applied to it.

Besides this, a dot could also be used in the same way as today: when it was placed after a note that was nominally binary (e.g., a breve in tempus imperfectum), it augmented it by one half (punctus augmentationis).

For instance, a breve in prolatio maior, which could be thought of as being composed of two perfect semibreves, could be imperfected by an adjacent minim, taking away one third of one of its two halves, thus reducing its total length from 6 to 5 (ex.[j]).

This has led to a certain amount of uncertainty and controversy over the correct interpretation of these notation devices, both in contemporary theory and in modern scholarship.

The resulting rhythmic effect, as expressed in modern notation, differs somewhat according to whether the affected notes were normally perfect or imperfect according to the basic mensuration of the music.

[a–b]), coloration creates the effect of a hemiola: three binary rhythmic groups in the space normally taken up by two ternary ones, but with the next smaller time units (semibreves in [a], minims in [b]) remaining constant.

)[16] The use of colored notes (at that time written in red) was introduced by Philippe de Vitry and flourished in the so-called ars subtilior of the late 14th century.

The example above, the chanson "Belle, bonne, sage" by Baude Cordier, written in a heart-shaped manuscript, is a rhythmically complex piece of ars subtilior.

In such cases, the music was typically notated only once, and several different mensuration signs were placed in front of it together, often supplemented with a verbal instruction of how it should be executed (called a "canon").

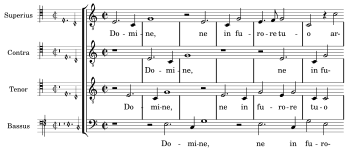

Pieces that demanded simultaneous execution of versions of the same music, i.e., contrapunctal canons, were written by several composers of the Franco-Flemish school in the late 15th and early 16th century, such as Josquin des Prez, Johannes Ockeghem or Pierre de la Rue.

Ockeghem's Missa prolationum is famous for systematically exploring different ways of combining pairs of voices in mensural canons.

The G-clef developed a curved ornamental swash typically attached to the top of the letter, which ultimately evolved into the loop shape of the modern form.

[18] In Medieval and Renaissance music accidentals were often not written but left to the performer to infer according to the rules of counterpoint and musica ficta.

Explicit sharps and flats apply to immediate repetitions of the pitch (there being of course no barlines) and are cancelled by rests as well as intervening notes.

This helps performers to prepare to sing the next note without having to look away from the current passage (analogous to the catchword in older printed books).

Franco, in his Ars cantus mensurabilis, was the first to describe the relations between maxima, longa and breve in terms that were independent of the fixed patterns of earlier rhythmic modes.

The decisive refinements that made notation even of extremely complex rhythmic patterns on multiple hierarchical metric levels possible were introduced in France during the time of the Ars nova, with Philippe de Vitry as the most important theoretician.

A number of special editorial conventions for such transcriptions are common, especially in scholarly editions, where it is desirable that the basic characteristics of the original notation should be recoverable from the modern text.

A special issue in representing Renaissance music is how to deal with its characteristic free-flowing rhythms, where modern bar lines can seem to overly highlight what is part of the natural articulation points of the melodic units.

4 meter typical of that era. It is written mostly in longa and breve notes. Longa notes highlighted in red are perfect, the others imperfect. The two breves in m. 22 would normally imply alteration (s-l), but harmonic considerations lead most editors to assume the scribe simply forgot to add a stem to the first note. [ citation needed ] ⓘ