Mentalism

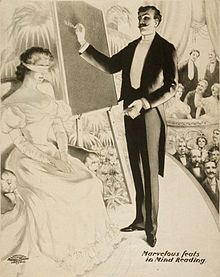

Mentalists perform a theatrical act that includes special effects that may appear to employ psychic or supernatural forces but that is actually achieved by "ordinary conjuring means",[1] natural human abilities (i.e. reading body language, refined intuition, subliminal communication, emotional intelligence), and an in-depth understanding of key principles from human psychology or other behavioral sciences.

[2][3][4] Performances may appear to include hypnosis, telepathy, clairvoyance, divination, precognition, psychokinesis, mediumship, mind control, memory feats, deduction, and rapid mathematics.

Some well-known magicians, such as Penn & Teller, and James Randi, argue that a key differentiation between a mentalist and someone who purports to be an actual psychic is that the former is open about being a skilled artist or entertainer who accomplishes their feats through practice, study, and natural means, while the latter may claim to actually possess genuine supernatural, psychic, or extrasensory powers and, thus, operates unethically.

[1][9][10] Renowned mentalist Joseph Dunninger, who also worked to debunk fraudulent mediums,[11] captured this key sentiment when he explained his impressive abilities in the following way: "Any child of ten could do this – with forty years of experience.

Much of what modern mentalists perform in their acts can be traced back directly to "tests" of supernatural power that were carried out by mediums, spiritualists, and psychics in the 19th century.

[14] Paracelsus reiterated the theme, so reminiscent of the ancient Greeks, that three principias were incorporated into humanity: the spiritual, the physical, and mentalistic phenomena.

[15] The mentalist act generally cited as one of the earliest on record in the modern era was performed by diplomat and pioneering sleight-of-hand magician Girolamo Scotto in 1572.

[5] The performance of mentalism may utilize conjuring principles including sleights, feints, misdirection, and other skills of street or stage magic.

[16] Nonetheless, modern mentalists also now increasingly incorporate insights from human psychology and behavioral sciences to produce unexplainable experiences and effects for their audiences.

[17] Mentalists typically seek to explain their effects as manifestations of psychology, hypnosis, an ability to influence by subtle verbal cues, an acute sensitivity to body language, etc.

One popular version - known as the "acidus novus" peek - requires the spectator to write her thought on the bottom right-hand corner of the billet.

In the course of this action he is able, unobserved by the audience, to slip his thumb between the folds of the billet and expose a view of the bottom right-hand quadrant.

Either way, the mentalist will use the occasion to obtain information from the spectator covertly for later revelation, either by traditional sleight of hand methods such as a billet peek, or by using electronic gimmickry such as a Parapad.

When the spectator’s covertly obtained information or forced choice is revealed, this greatly enhances the effect from the point of view of the wider audience.

Magicians and mentalists frequently use grand gestures, animated movement, music, and chatter to distract attention from a sneaky maneuver that sets up the trick.

[20] This technique involves making calculated guesses and drawing logical conclusions about a person by carefully observing their appearance, responses, mannerisms, vocal tones, and other unconscious reactions.

Mentalists leverage these cues along with high probability assumptions about human nature to come up with surprisingly accurate character insights and details about someone.

[21] Hot reading refers to the practice of gathering background information about the audience or participants before doing a mentalism act or seance.

Some contemporary performers, such as Derren Brown, explain that their results and effects are from using natural skills, including the ability to master magic techniques and showmanship, read body language, and influence audiences with psychological principles, such as suggestion.

[34] There are mentalists, including Maurice Fogel, Kreskin, Chan Canasta, and David Berglas, who make no specific claims about how effects are achieved and may leave it up to the audience to decide, creating what has been described as "a wonderful sense of ambiguity about whether they possess true psychic ability or not.

[6][5] The argument is that mentalism invokes belief and imagination that, when presented properly, may allow the audience to interpret a given effect as "real" or may at least provide enough ambiguity that it is unclear whether it is actually possible to somehow achieve.

[37][2] This lack of certainty about the limits of what is real may lead individuals in an audience to reach different conclusions and beliefs about mentalist performers' claims – be they about their various so-called psychic abilities, photographic memory, being a "human calculator", power of suggestion, NLP, or other skills.

[38][2] Magicians often ask the audience to suspend their disbelief, ignore natural laws, and allow their imagination to play with the various tricks they present.

[39][2] Everyone knows that the magician cannot really achieve the impossible feats shown, such as sawing a person in half and putting them back together, but that level of certainty does not generally exist among the mentalist's audience.

[41] Mentalism techniques have, on occasion, been allegedly used outside the entertainment industry to influence the actions of prominent people for personal and/or political gain.

Famous examples of accused practitioners include: In Albert Einstein's preface to Upton Sinclair's 1930 book on telepathy, Mental Radio, he supported his friend's endeavor to test the abilities of purported psychics and skeptically suggested: "So if somehow the facts here set forth rest not upon telepathy, but upon some unconscious hypnotic influence from person to person, this also would be of high psychological interest.