Project Mercury

An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Union.

This came as a shock to the American public, and led to the creation of NASA to expedite existing US space exploration efforts, and place most of them under civilian control.

The Mercury space capsule was produced by McDonnell Aircraft, and carried supplies of water, food and oxygen for about one day in a pressurized cabin.

[11] Americans were shocked when the Soviet Union placed the first satellite into orbit in October 1957, leading to a growing fear that the US was falling into a "missile gap".

[15] The limit of space (also known as the Kármán line) was defined at the time as a minimum altitude of 62 mi (100 km), and the only way to reach it was by using rocket-powered boosters.

[16][17] This created risks for the pilot, including explosion, high g-forces and vibrations during lift off through a dense atmosphere,[18] and temperatures of more than 10,000 °F (5,500 °C) from air compression during reentry.

[25] T. Keith Glennan had been appointed the first Administrator of NASA, with Hugh L. Dryden (last Director of NACA) as his Deputy, at the creation of the agency on October 1, 1958.

[30] In keeping with his desire to keep from giving the US space program an overtly military flavor, President Eisenhower at first hesitated to give the project top national priority (DX rating under the Defense Production Act), which meant that Mercury had to wait in line behind military projects for materials; however, this rating was granted in May 1959, a little more than a year and a half after Sputnik was launched.

[33] Two weeks earlier, North American Aviation, based in Los Angeles, was awarded a contract for Little Joe, a small rocket to be used for development of the launch escape system.

[40] Astronaut training took place at Langley Research Center in Virginia, Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio, and Naval Air Development Center Johnsville in Warminster, PA.[41] Langley wind tunnels[42] together with a rocket sled track at Holloman Air Force Base at Alamogordo, New Mexico were used for aerodynamic studies.

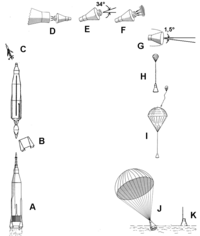

[48] It had a convex base, which carried a heat shield (Item 2 in the diagram below)[53] consisting of an aluminum honeycomb covered with multiple layers of fiberglass.

[60] Underneath the seat was the environmental control system supplying oxygen and heat,[61] scrubbing the air of CO2, vapor and odors, and (on orbital flights) collecting urine.

[62] The recovery compartment (4)[63] at the narrow end of the spacecraft contained three parachutes: a drogue to stabilize free fall and two main chutes, a primary and reserve.

Near his left hand was a manual abort handle to activate the launch escape system if necessary prior to or during liftoff, in case the automatic trigger failed.

[74] A cabin atmosphere of pure oxygen at a low pressure of 5.5 psi or 38 kPa (equivalent to an altitude of 24,800 feet or 7,600 metres) was chosen, rather than one with the same composition as air (nitrogen/oxygen) at sea level.

[62] In such case, or failure of the cabin pressure for any reason, the astronaut could make an emergency return to Earth, relying on his suit for survival.

[83] The expected short flight times meant that this was overlooked, although after Alan Shepard had a launch delay of four hours, he was forced to urinate in his suit, short-circuiting some of the electrodes monitoring his vital signs.

[122] The Little Joe rocket used solid-fuel propellant and was originally designed in 1958 by NACA for suborbital crewed flights, but was redesigned for Project Mercury to simulate an Atlas-D launch.

[128] The Jupiter rocket, also developed by Wernher von Braun's team at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, was considered as well for intermediate Mercury suborbital flights at a higher speed and altitude than Redstone, but this plan was dropped when it turned out that man-rating Jupiter for the Mercury program would actually cost more than flying an Atlas due to economics of scale.

[129][130] Jupiter's only use other than as a missile system was for the short-lived Juno II launch vehicle, and keeping a full staff of technical personnel around solely to fly a few Mercury capsules would result in excessively high costs.

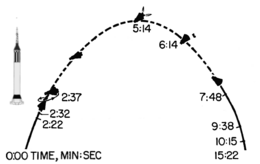

[138] Mercury-Redstone 3, Shepard's 15 minute and 28 second flight of the Freedom 7 capsule demonstrated the ability to withstand the high g-forces of launch and atmospheric re-entry.

[148][149] Deke Slayton was grounded in 1962 due to a heart condition, but remained with NASA and was appointed senior manager of the Astronaut Office and later additionally assistant director of Flight Crew Operations at the beginning of Project Gemini.

Civilian NASA X-15 pilot Neil Armstrong was also disqualified, though he had been selected by the US Air Force in 1958 for its Man in Space Soonest program, which was replaced by Mercury.

[7] The college degree requirement excluded the USAF's X-1 pilot, then-Lt Col (later Brig Gen) Chuck Yeager, the first person to exceed the speed of sound.

[56][n 17] The space vehicle moved gradually to a horizontal attitude until, at an altitude of 87 nautical miles (161 km), the sustainer engine shut down and the spacecraft was inserted into orbit (D).

[215] In the Control Center, the data were displayed on boards on each side of a world map, which showed the position of the spacecraft, its ground track and the place it could land in an emergency within the next 30 minutes.

[138] John Glenn, the third Mercury astronaut to fly, became the first American to reach orbit on February 20, 1962, but only after the Soviets had launched a second cosmonaut, Gherman Titov, into a day-long flight in August 1961.

[222] One flight of a Scout rocket attempted to launch a specialized satellite equipped with Mercury communications components for testing the ground tracking network, but the booster failed soon after liftoff.

[283] It did not win the race against the Soviet Union, but gave back national prestige and was scientifically a successful precursor of later programs such as Gemini, Apollo and Skylab.

[289][n 42] Afterwards, a majority of the American public supported human spaceflight, and, within a few weeks, Kennedy announced a plan for a crewed mission to land on the Moon and return safely to Earth before the end of the 1960s.