Merian C. Cooper

Merian Caldwell Cooper (October 24, 1893 – April 21, 1973) was an American filmmaker, actor, producer and air officer.

He was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1952 and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

In 1925, he and Ernest B. Schoedsack went to Iran and made Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life, a documentary about the Bakhtiari people.

Naval Academy,[2]: 19 but was expelled during his senior year for "hell raising and for championing air power".

[4] In 1916, Cooper worked for the Minneapolis Daily News as a reporter, where he met Delos Lovelace.

[2]: 22 In 1916, Cooper joined the Georgia National Guard to help chase Pancho Villa in Mexico.

[2]: 24–25 In October 1917, six months after the American entry into World War I, Cooper went to France with the 201st Squadron.

[2]: 26–27 Cooper served as a DH-4 bomber pilot with the United States Army Air Service during World War I.

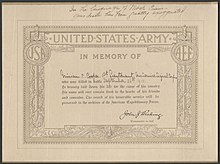

Cooper's father received a letter from Merian around the time the death certificate arrived.

Merian C. Cooper sent the copy back to the Army with the notation on top "In the language of Mark Twain Your death has been greatly exaggerated.

"[8] Captain Cooper remained in the Air Service after the war; he helped with Herbert Hoover's U.S. Food Administration that provided aid to Poland.

[6] On July 13, 1920, his plane was shot down, and he spent nearly nine months in a Soviet prisoner of war camp[9] where the writer Isaac Babel interviewed him.

As part of the journey, he traveled to Abyssinia, or the Ethiopian Empire, where he met their prince regent, Ras Tefari, later known as Emperor Haile Selassie I.

In 1924, Cooper joined Schoedsack and Marguerite Harrison who had embarked on an expedition that would be turned into the film Grass (1925).

Cooper became a member of the Explorers Club of New York in January 1925 and was asked to give lectures and attend events due to his extensive traveling.

[9] While he was on the board, Cooper did not devote his full attention to the organization; he took time in 1929 and 1930 to work on the script for King Kong.

[2]: 258 Cooper said that he thought of King Kong after he had a dream that a giant gorilla was terrorizing New York City.

[14] He was going to have a giant gorilla fight a Komodo dragon or other animal, but found that the technique of interlacing that he wanted to use would not provide realistic results.

Selznick became the vice president of RKO and asked Cooper to join him in September 1931, although he had only produced three films thus far in his career.

The iconic scene in which Kong is atop of the Empire State Building was almost canceled by Cooper for legal reasons, but was kept in the film because RKO bought the rights to The Lost World.

[2]: 229, 231 Overlapping with the production of King Kong was the making of The Most Dangerous Game, which began in May 1932. Cooper once again worked with Schoedsack to produce the film.

According to Hollywood folklore, the decision was made after previews in January 1933, during which audience members either fled the theater in terror or talked about the ghastly scene throughout the remainder of the movie.

[2]: 362, 387 Selznick left RKO before the release of King Kong, and Cooper served as production chief from 1933 to 1934 with Pan Berman as his executive assistant.

[15] In the 2005 remake of King Kong, upon learning that Fay Wray was not available because she was making a film at RKO, Carl Denham (Jack Black) replies, "Cooper, huh?

"[2]: 259, 263 After these disappointments, Pioneer Pictures released a short film in three-strip technicolor called La Cucaracha, which was well-received.

[2]: 267–269 Cooper helped to advocate and pave the way for the ground-breaking technology of technicolor,[9] as well as the widescreen process called Cinerama.

[22] On October 25, 1942, a CATF raid consisting of 12 B-25s and 7 P-40s, led by Colonel Cooper, successfully bombed the Kowloon Docks at Hong Kong.

Cooper continued to outline movies to be shot in Cinerama, but C. V. Whitney Productions only produced a few films.

The other honorees were Roy Chapman Andrews, Robert Bartlett, Frederick Russell Burnham, Richard E. Byrd, George Kruck Cherrie, James L. Clark, Lincoln Ellsworth, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, George Bird Grinnell, Charles Lindbergh, Donald Baxter MacMillan, Clifford H. Pope, George Palmer Putnam, Kermit Roosevelt, Carl Rungius, Stewart Edward White, and Orville Wright.

[30] His film The Quiet Man was nominated for Best Picture that year, but lost to Cecil B. DeMille's The Greatest Show on Earth.