Meroë

Meroë (/ˈmɛroʊiː/;[1] also spelled Meroe;[2] Meroitic: Medewi; Arabic: مرواه, romanized: Meruwah and مروي, Meruwi; Ancient Greek: Μερόη, romanized: Meróē) was an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum.

[6] The Kingdom of Kush which housed the city of Meroë represents one of a series of early states located within the middle Nile.

The city of Meroë was located along the middle Nile which is of much importance due to the annual flooding of the Nile river valley and the connection to many major river systems such as the Niger which aided with the production of pottery and iron characteristic to the Meroitic kingdom that allowed for the rise in power of its people.

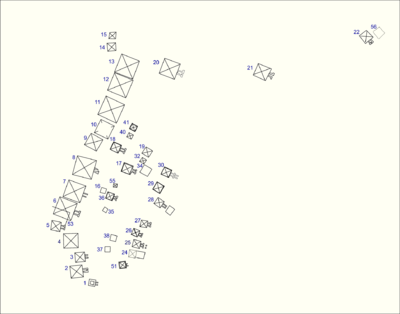

"[12][13] Excavations revealed evidence of important, high ranking Kushite burials from the Napatan Period (c. 800 – c. 280 BC) in the vicinity of the settlement called the Western Cemetery.

The importance of the town gradually increased from the beginning of the Meroitic Period, especially from the reign of Arakamani (c. 280 BC) when the royal burial ground was transferred to Meroë from Napata (Gebel Barkal).

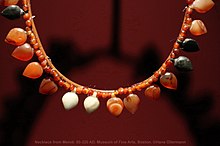

[11] The first king of the period is Arakamani (270–260 BC), the last ruler is Queen Amanitore (mid/late 1st century AD) Many artifacts were found in Meroitic tombs from around this time.

In retaliation, the Nubians crossed the lower border of Egypt and looted many statues from the Egyptian towns near the first cataract of the Nile at Aswan.

Roman forces later reclaimed some of the statues, and others were returned following the peace treaty signed in 22 BC between Rome and Meroë under Augustus and Amanirenas, respectively.

One looted head, from a statue of the emperor Augustus, was buried under the steps of a temple in Meroë; it is now kept in the British Museum.

The Emperor Nero sent a party of Praetorian soldiers under the command of a tribune and two centurions into this country, who reached the city of Meroë where they were given an escort, then proceeded up the White Nile until they encountered the swamps of the Sudd.

[16]: 18f The kingdom of Meroë began to fade as a power by the 1st or 2nd century AD, sapped by the war with Roman Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.

and of Hasa and of the Bougaites and of Taimo...While some authorities interpret these inscriptions as proof that the Axumites destroyed the Kingdom of Kush, others note that archeological evidence points to an economic and political decline in Meroë around 300.

[23] Jewish oral tradition avers that Moses, in his younger years, had led an Egyptian military expedition into Sudan (Kush), as far as the city of Meroë, which was then called Saba.

The city was built near the confluence of two great rivers and was encircled by a formidable wall, and governed by a renegade king.

[24] Archibald Sayce reportedly referred to it as "the Birmingham of Africa",[25] because of perceived vast production and trade of iron (a contention that is a matter of debate in modern scholarship).

[27] At its peak, the rulers of Meroë controlled the Nile Valley north to south, over a straight-line distance of more than 1,000 km (620 mi).

Although the people of Meroë also had southern deities such as Apedemak, the lion-son of Sekhmet (or Bast, depending upon the region), they also continued worshipping ancient Egyptian gods that they had brought with them.

[29] By the 3rd century BC, a new indigenous alphabet, the Meroitic, consisting of twenty-three letters, replaced Egyptian script.

[31][32] Claude Rilly, based on its syntax, morphology, and known vocabulary, proposes that Meroitic, like the Nobiin language, instead belongs to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan family.

[33][34][35] The site of Meroë was brought to the knowledge of Europeans in 1821 by the French mineralogist Frédéric Cailliaud (1787–1869), who published an illustrated in-folio describing the ruins.

"[2] Margoliouth continues, The ruins were examined in 1844 by C. R. Lepsius, who brought many plans, sketches and copies, besides actual antiquities, to Berlin.

Further excavations were carried on by E. A. Wallis Budge in the years 1902 and 1905, the results of which are recorded in his work, The Egyptian Sudan: its History and Monuments…[37] Troops were furnished by Sir Reginald Wingate, governor of the Sudan, who made paths to and between the pyramids, and sank shafts, &c. It was found that the pyramids were regularly built over sepulchral chambers, containing the remains of bodies either burned or buried without being mummified.

The most interesting objects found were the reliefs on the chapel walls, already described by Lepsius, and containing the names with representations of queens and some kings, with some chapters of the Book of the Dead; some steles with inscriptions in the Meroitic language, and some vessels of metal and earthenware.

In 1910, in consequence of a report by Professor Archibald Sayce, excavations were commenced in the mounds of the town and the necropolis by J[ohn] Garstang on behalf of the University of Liverpool, and the ruins of a palace and several temples were discovered, built by the Meroite kings.